Kloster La Tourette

If we devour the latest issues of magazines featuring projects by world-renowned names, our own creations will lead to mere copying of theirs. It is far better to learn from examples that have withstood the corrosion of time. A healthy individual will not blindly imitate two-hundred-year-old structures, but based on their experiences, they may attempt a new interpretation of their timeless principles. Charles-Édouard Jeannaret was a master of this.

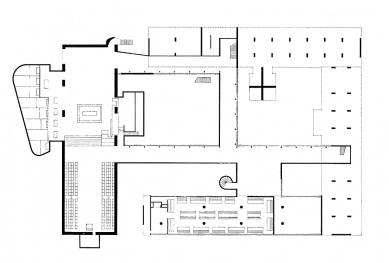

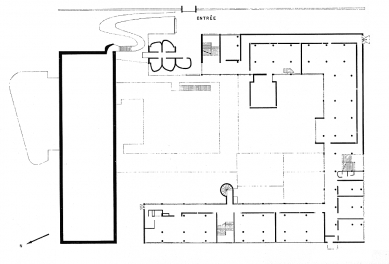

Over time, he began to focus on the construction of church buildings. He felt that his position was strong enough to build them based on his own architectural vocabulary. Three buildings testify to this: the pilgrimage chapel in Ronchamp from 1955, the Abbey of La Tourette from 1960, and the planned church for Firminy designed in 1963. Each of them differs significantly from the others in construction, but each is permeated by the same artistic spirit. This spirit is perhaps most pronounced in the Abbey of La Tourette in Eveux-sur-l'Arbresle near Lyon, where Le Corbusier conceived the church and the complex of monastic buildings as two distinct elements. The three-sided monastic complex spatially separates from the fourth side - the church.

At the suggestion of Dominican Father Couturier, Le Corbusier visited the Cistercian monastery of Le Thoronet in Provence, abandoned since the French Revolution. This monastery from the late twelfth century has a similarly concentrated plan as La Tourette, with a three-sided structure for the monks intersecting with its church. The monastic buildings in Le Thoronet also have a promenade on the roof, which evidently reinforced Le Corbusier's idea of a balcony roof terrace at the Abbey of La Tourette.

Le Corbusier concludes his foreword to the publication about the Le Thoronet monastery with a statement about his respect for the past, "Light and shadow are the amplifiers of this architecture of truth, calm, and strength. Nothing more needs to be added. In these days of 'cruel concrete', let us greet, bless, and salute, as we walk on our way, in such a miraculous encounter".

The Dominicans owned a large property, allowing Le Corbusier to freely decide its exact location at the abbey. He chose a site next to a forest, with a wide view down the slope and across the river valley: an old chateau still stands at the entrance, nestled among the trees.

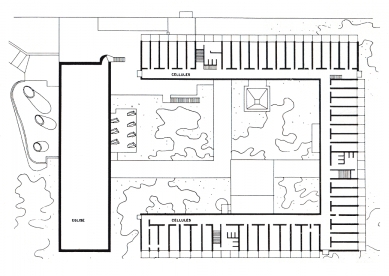

Rarely did Le Corbusier employ such force of expression and such variety in every detail as in La Tourette. There is a constant interplay of strictly geometric and organically curved lines here. Stark verticals are interrupted at the monk's complex by large windows of the common rooms, but the gaps between them continually change. The protruding loggias of the two upper floors share a consistent surface texture on the outside and horizontal window slits on the inside. Below these slits are three rows of rectangular window openings, differently arranged on each floor. Le Corbusier's adventurous imagination is well displayed in the church block. At the end of its flat roof, two sloping walls rise, supporting an asymmetrically protruding box that serves as a bell tower.

The oratory in the courtyard for private prayer, standing on two crossed walls, is placed in direct relation to the library. Its helm is an extended pyramid, a recollection of Celestine’s tomb in Rome, which Le Corbusier sketched on his early trip to Italy. Light penetrates inside through narrow vertical slits at the corners of the oratory, and at the back of the slanting pyramid, a light funnel is used.

The building for the monks is held together externally by two protruding upper floors, which house one hundred cells for the monks. As was later Le Corbusier's custom, the building's austerity is related to and animated by the lower floors by narrowing and widening the gaps between the sections of the continuous glass wall.

However, this was only a brief summary of the construction. We have said nothing about the special qualities of the architecture intended for the monastic community, focused on the inner life. It seems contradictory to the fact that the entire construction breathes passionate vitality.

One must be amazed that the courtyard of La Tourette lacks the usually essential ambulatory; instead, the courtyard is occupied by sculpturally treated passages and staircases. The ambulatory is absent because the complex mostly rests on pilotis, which prevent the desired strict closure of the ambulatory. The use of these pilotis, which have a different height on each side, allowed for avoiding contact with the slope. In its original height, the slope extended into the courtyard. The sloping terrain is balanced so that against the hill, the building has three stories and over the valley four stories, so the upper protruding floors are on the same level.

Le Corbusier certainly intended to create a continuous flat roof, bordered by walls taller than a person, which could serve as a space for meditation instead of the usual ground-level cross corridor. The view concentrates on the infinity of the heavens. However, the direct confrontation with the sky, to which Le Corbusier continually returned, was probably not something the monks wished for, as they are rarely seen on the roof. Grass is already growing on the roof of La Tourette.

Three large cult openings, blue, red, and yellow, illuminate the low crypt adjacent to the main church from above. The three funnels on the roof that provide this light tilt in different directions, so the intensity of each of the three colors changes throughout the day. Side altars for reading mass stand somewhat close together, elevated on steps, but without intermediary links. The walls behind the altars do not extend to the floor, and the colored light from the light openings floats above them and partially penetrates into the main church. The walls have different heights; the architect placed them at different reciprocal angles and painted them red, blue, and yellow. Set apart from them is a curved wall, again showcasing the interplay of geometric and organic forms.

The organic form holds for Le Corbusier a mythical connotation that cannot be bound by logical analogy. He always sought to gain experience from past times during his travels and was interested in crystalline Greek forms as well as forms of Roman vaults or Islamic and Gothic architecture. His quest for internal similarities had nothing to do with art history: he absorbed the experience of the entire architectural development. It is no coincidence that the tower of Ronchamp has been compared to a primitive cult structure.

The interior of the main church of La Tourette is a pure and crystalline space. Down in the middle of the floor runs a narrow black line (made of asphalt) from the steps of the main altar to the lay altar. The organ protrudes from the rear wall; besides that, there are only square black clocks, which hide from all eyes. In contrast to the colored light that enters through low horizontal windows along both sides of the church, white light also flows in through a narrow horizontal slit at the very top of the end wall, which rises uninterrupted almost to the ceiling. The white light flows inside and enters through a square opening in the roof.

Sigfried Giedion (1888-1968) was a Swiss historian and theorist of architecture. As a long-term secretary of CIAM (International Congress of Modern Architecture), he became closely acquainted with many leading architects of the 1920s to 1960s, particularly with Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Aalto, Sert, Breuer, Utzon, and incorporated this experience into his texts. In CIAM, he tried to eliminate the influence of the leftist faction led by the Swiss Hannes Meyer and Hans Schmidt. He approached the history of architecture more or less formally, as a history of new spatial, structural, and formal inventions; only in the 1960s did he begin to consider the symbolic significance and the connection of modernity with tradition more, which is ultimately reflected in the essay on La Tourette. Among Giedion's most significant works is the book Space, Time, and Architecture, which became the basis for Giedion's lectures at Harvard University and which he published in four continuously updated editions starting in 1941.

Domingo de Guzmán (circa 1170-1221), also Saint Dominic, was a Spanish priest and founder of the Dominican Order. Coming from a noble family, he chose the priesthood; for several years, he was a canon in Órma. In southern France, where he accompanied his bishop, he encountered the Albigensians, whose heresy he sought to eliminate through preaching. He founded a religious order of preachers (i.e., Dominicans), which provided for its livelihood through alms and became the second great mendicant order, canonized in 1233.

Dominicans are members of the Catholic religious order founded by Domingo de Guzmán (Saint Dominic) as a response to popular heresy; the order was approved by the Pope in 1216. The official name, Order of Preachers, reflects its mission. Dominicans, among other activities, engage in teaching, research, publishing and journalism, and spiritual care for students and the intelligentsia. Among the main spiritual leaders of the Dominicans are Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas, whose doctrine became the order's doctrine in 1342 and later that of the entire church. Since 1231, Dominicans have been appointed to the Inquisition. The basic unit of the order is a convent led by an elected prior, and the superior territorial unit is often a province headed by a provincial prior. The order is led by a master elected by the general chapter. They have been active in the Czech lands since the 14th century.

Petr Šmídek, 2003

Abbey of Sainte Marie de la Tourette

Long before Le Corbusier took on the pilot chapel in Ronchamp or the Abbey of La Tourette, he was deeply preoccupied with the problem of the church and the mystical quality of its space. Once, years before he received an order to build a church, I asked him how he envisioned a modern sacred space, and he told me that he would allow a tall tower to grow from the center and build a series of cross-shaped concrete beams, one above the other, so that for the eye looking upward, it might seem that the tower reaches to infinity.Over time, he began to focus on the construction of church buildings. He felt that his position was strong enough to build them based on his own architectural vocabulary. Three buildings testify to this: the pilgrimage chapel in Ronchamp from 1955, the Abbey of La Tourette from 1960, and the planned church for Firminy designed in 1963. Each of them differs significantly from the others in construction, but each is permeated by the same artistic spirit. This spirit is perhaps most pronounced in the Abbey of La Tourette in Eveux-sur-l'Arbresle near Lyon, where Le Corbusier conceived the church and the complex of monastic buildings as two distinct elements. The three-sided monastic complex spatially separates from the fourth side - the church.

At the suggestion of Dominican Father Couturier, Le Corbusier visited the Cistercian monastery of Le Thoronet in Provence, abandoned since the French Revolution. This monastery from the late twelfth century has a similarly concentrated plan as La Tourette, with a three-sided structure for the monks intersecting with its church. The monastic buildings in Le Thoronet also have a promenade on the roof, which evidently reinforced Le Corbusier's idea of a balcony roof terrace at the Abbey of La Tourette.

Le Corbusier concludes his foreword to the publication about the Le Thoronet monastery with a statement about his respect for the past, "Light and shadow are the amplifiers of this architecture of truth, calm, and strength. Nothing more needs to be added. In these days of 'cruel concrete', let us greet, bless, and salute, as we walk on our way, in such a miraculous encounter".

The Dominicans owned a large property, allowing Le Corbusier to freely decide its exact location at the abbey. He chose a site next to a forest, with a wide view down the slope and across the river valley: an old chateau still stands at the entrance, nestled among the trees.

Rarely did Le Corbusier employ such force of expression and such variety in every detail as in La Tourette. There is a constant interplay of strictly geometric and organically curved lines here. Stark verticals are interrupted at the monk's complex by large windows of the common rooms, but the gaps between them continually change. The protruding loggias of the two upper floors share a consistent surface texture on the outside and horizontal window slits on the inside. Below these slits are three rows of rectangular window openings, differently arranged on each floor. Le Corbusier's adventurous imagination is well displayed in the church block. At the end of its flat roof, two sloping walls rise, supporting an asymmetrically protruding box that serves as a bell tower.

The oratory in the courtyard for private prayer, standing on two crossed walls, is placed in direct relation to the library. Its helm is an extended pyramid, a recollection of Celestine’s tomb in Rome, which Le Corbusier sketched on his early trip to Italy. Light penetrates inside through narrow vertical slits at the corners of the oratory, and at the back of the slanting pyramid, a light funnel is used.

The building for the monks is held together externally by two protruding upper floors, which house one hundred cells for the monks. As was later Le Corbusier's custom, the building's austerity is related to and animated by the lower floors by narrowing and widening the gaps between the sections of the continuous glass wall.

However, this was only a brief summary of the construction. We have said nothing about the special qualities of the architecture intended for the monastic community, focused on the inner life. It seems contradictory to the fact that the entire construction breathes passionate vitality.

One must be amazed that the courtyard of La Tourette lacks the usually essential ambulatory; instead, the courtyard is occupied by sculpturally treated passages and staircases. The ambulatory is absent because the complex mostly rests on pilotis, which prevent the desired strict closure of the ambulatory. The use of these pilotis, which have a different height on each side, allowed for avoiding contact with the slope. In its original height, the slope extended into the courtyard. The sloping terrain is balanced so that against the hill, the building has three stories and over the valley four stories, so the upper protruding floors are on the same level.

Le Corbusier certainly intended to create a continuous flat roof, bordered by walls taller than a person, which could serve as a space for meditation instead of the usual ground-level cross corridor. The view concentrates on the infinity of the heavens. However, the direct confrontation with the sky, to which Le Corbusier continually returned, was probably not something the monks wished for, as they are rarely seen on the roof. Grass is already growing on the roof of La Tourette.

Three large cult openings, blue, red, and yellow, illuminate the low crypt adjacent to the main church from above. The three funnels on the roof that provide this light tilt in different directions, so the intensity of each of the three colors changes throughout the day. Side altars for reading mass stand somewhat close together, elevated on steps, but without intermediary links. The walls behind the altars do not extend to the floor, and the colored light from the light openings floats above them and partially penetrates into the main church. The walls have different heights; the architect placed them at different reciprocal angles and painted them red, blue, and yellow. Set apart from them is a curved wall, again showcasing the interplay of geometric and organic forms.

The organic form holds for Le Corbusier a mythical connotation that cannot be bound by logical analogy. He always sought to gain experience from past times during his travels and was interested in crystalline Greek forms as well as forms of Roman vaults or Islamic and Gothic architecture. His quest for internal similarities had nothing to do with art history: he absorbed the experience of the entire architectural development. It is no coincidence that the tower of Ronchamp has been compared to a primitive cult structure.

The interior of the main church of La Tourette is a pure and crystalline space. Down in the middle of the floor runs a narrow black line (made of asphalt) from the steps of the main altar to the lay altar. The organ protrudes from the rear wall; besides that, there are only square black clocks, which hide from all eyes. In contrast to the colored light that enters through low horizontal windows along both sides of the church, white light also flows in through a narrow horizontal slit at the very top of the end wall, which rises uninterrupted almost to the ceiling. The white light flows inside and enters through a square opening in the roof.

Translation and biography of Gideon: Prof. Rostislav Švácha

Sigfried Giedion (1888-1968) was a Swiss historian and theorist of architecture. As a long-term secretary of CIAM (International Congress of Modern Architecture), he became closely acquainted with many leading architects of the 1920s to 1960s, particularly with Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Aalto, Sert, Breuer, Utzon, and incorporated this experience into his texts. In CIAM, he tried to eliminate the influence of the leftist faction led by the Swiss Hannes Meyer and Hans Schmidt. He approached the history of architecture more or less formally, as a history of new spatial, structural, and formal inventions; only in the 1960s did he begin to consider the symbolic significance and the connection of modernity with tradition more, which is ultimately reflected in the essay on La Tourette. Among Giedion's most significant works is the book Space, Time, and Architecture, which became the basis for Giedion's lectures at Harvard University and which he published in four continuously updated editions starting in 1941.

Domingo de Guzmán (circa 1170-1221), also Saint Dominic, was a Spanish priest and founder of the Dominican Order. Coming from a noble family, he chose the priesthood; for several years, he was a canon in Órma. In southern France, where he accompanied his bishop, he encountered the Albigensians, whose heresy he sought to eliminate through preaching. He founded a religious order of preachers (i.e., Dominicans), which provided for its livelihood through alms and became the second great mendicant order, canonized in 1233.

Dominicans are members of the Catholic religious order founded by Domingo de Guzmán (Saint Dominic) as a response to popular heresy; the order was approved by the Pope in 1216. The official name, Order of Preachers, reflects its mission. Dominicans, among other activities, engage in teaching, research, publishing and journalism, and spiritual care for students and the intelligentsia. Among the main spiritual leaders of the Dominicans are Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas, whose doctrine became the order's doctrine in 1342 and later that of the entire church. Since 1231, Dominicans have been appointed to the Inquisition. The basic unit of the order is a convent led by an elected prior, and the superior territorial unit is often a province headed by a provincial prior. The order is led by a master elected by the general chapter. They have been active in the Czech lands since the 14th century.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment