Jean Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre

Inspired by tradition, formed by modern technology, this centre celebrates and explains the Melanesian culture of the Kanaks. Response to sea and site have generated a heraldic dance reflected in the waves.

‘The return to tradition is a myth ... No people has ever achieved that. The search for identity, for a model, I believe it lies before us ... Our identity is before us’: Jean-Marie Tjibaou’s vision informs the new cultural centre at Nouméa in New Caledonia. Tjibaou, sometime priest and doctoral student at the Sorbonne, was leader of the New Caledonian independence movement and, though he wanted his people to fully take part in the modern world, he was keenly aware of the need for his people to come to terms with their past and make a balance between traditional and world culture. ‘Although I can share with a non-Kanak what I possess of French culture, it is impossible for him to share the universal element within my culture’.

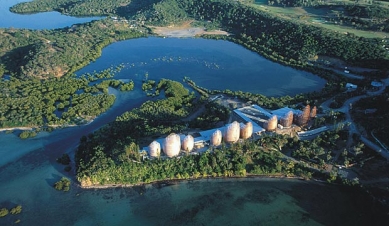

Tjibaou died in 1989, but already it had been decided to build a centre for the Agence de Développement de la Culture Kanak (ADCK), and an international competition was held in 1991. Renzo Piano won, and began to refine his design for the Centre Culturel Tjibaou with the help of local people including the leader’s widow, Marie Claude. The site which was given to the ADCK by the municipality of Nouméa, is a thin peninsula which sticks out south into the blue lagoon. (It was here that Tjibaou had held the Melanesia 2000 festival in 1975, one of the key moments in the struggle for cultural and political recognition by France.) Early on in the programme for the centre, the indigenous bush was supplemented with transplanted Norfolk Island pines, those wonderful, stiff architectural trees which so gracefully articulate the sky-lines of the islands of the south-western Pacific.

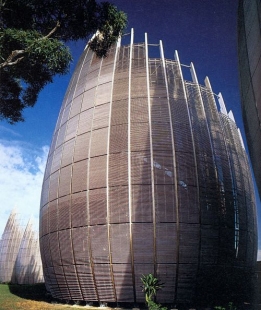

From the first, Piano was concerned to learn from local culture, buildings and nature, but he was determined not to end up with a kitsch replication of Kanak huts. He took from them the ideas of the village cluster and the ribbed hut structure in which tall thin curved timber members cluster together at the top and carry the cladding. In the original vernacular, the ribs are of palm saplings; in Piano’s (much larger) reinterpretation of the forms, they are made of laminated iroko, structurally linked by horizontal tubes and diagonal rod ties of stainless steel. The happy and carefully crafted conjunction of stainless steel and laminated timber is reminiscent of the IBM pavilion which travelled Europe so successfully over a decade ago, but here the long wooden pieces are not so finely pared, partly because they are much bigger to achieve resistance to cyclones and earthquakes, and partly because they have to be tall to make a celebratory figure.

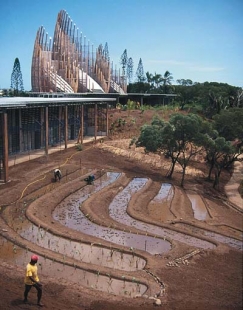

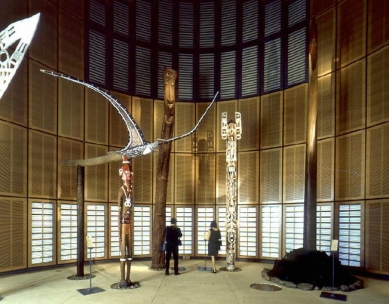

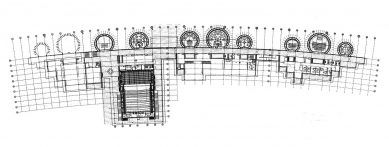

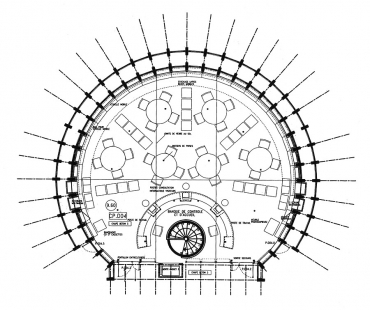

What Piano calls the ‘cases’, pavilions or abstracted huts, are of three heights, the tallest 28m, as high as an eight- or nine-storey urban building. They are arranged in three groups, the villages, in a very gently curving line that follows the axis of the peninsula. The cases are fundamentally circular in plan, but they open off a long connecting corridor, so the inner edge of each circle is honed off, allowing individual cases to lock into the connecting space, then beyond that into more conventional rectilinear volumes (sometimes but not always part of the spatial flow). Here, planted courts penetrate the building, the flat stainless steel and glass roofs are supported on laminated flitched iroko columns; volumes are largely defined by timber and glass louvres, which form part of the passive cooling system. To the north-west, there is a strip between the irregular edge of the building and the sea, densely planted and carved into with terraces and clearings for public extensions of the building as open-air exhibition and performance spaces. And for the pedestrian route round the peninsula’s perimeter which introduces visitors to the flora of the place and its mythic meanings, which are very powerful in Kanak culture.

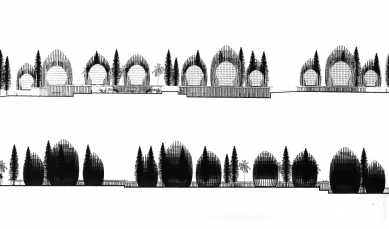

Externally, the cases stretch their curves among and over the tall verticals and horizontals of the pines and eucalypts, making a heraldic dance against the sky which is partnered by reflections rippling in the lagoon. Piano hopes that the rot-proof iroko ribs will weather to the same pale silvery grey as the trunks of the indigenous palm trees. As well as being an abstracted hut, each case is a sort of forest. Each curved outer rib is linked to a straight vertical one which forms part of the structure of the perimeter of the enclosed space. The curved ribs carry horizontal slats, which have some effect on modifying the effects of the often high winds, and internal conditions are controlled by a passive system which uses louvres at the base of the perimeter wall and on the opposite face of the complex. They are opened and closed according to wind direction and intensity, encouraging breezes through the spaces from which air is expelled along the highest points of the roofs.

It has to be admitted that the curved ribs have a largely symbolic role, but they do have a climate balancing function: ‘I decided to tone down the resemblance between “my” huts and reducing the length of the vertical elements and giving the shells more open form ... the staves no longer meet at the top, as had initially been planned. The wind tunnel [showed] that this produced a greater effect of dynamic ventilation.’ Yet they have deeper resonances, some literal: the wind surging through the slats of the open outer carapace gives ‘the huts a “voice”: ... it is that of the Kanak villages and their forests’.

Marie Claude Tjibaou, who is the president of the ADKC, understands the mediatory role of the building: ‘Today, everyone is coming to see the architecture. Little by little, we will bring people to ask: why these arcs, why these vaults’. They will be instrumental in helping the Kanaks achieve her husband’s ambition of telling ‘the world that we are neither escapees from prehistory nor archaeological remains, but men of flesh and blood’.

‘The return to tradition is a myth ... No people has ever achieved that. The search for identity, for a model, I believe it lies before us ... Our identity is before us’: Jean-Marie Tjibaou’s vision informs the new cultural centre at Nouméa in New Caledonia. Tjibaou, sometime priest and doctoral student at the Sorbonne, was leader of the New Caledonian independence movement and, though he wanted his people to fully take part in the modern world, he was keenly aware of the need for his people to come to terms with their past and make a balance between traditional and world culture. ‘Although I can share with a non-Kanak what I possess of French culture, it is impossible for him to share the universal element within my culture’.

Tjibaou died in 1989, but already it had been decided to build a centre for the Agence de Développement de la Culture Kanak (ADCK), and an international competition was held in 1991. Renzo Piano won, and began to refine his design for the Centre Culturel Tjibaou with the help of local people including the leader’s widow, Marie Claude. The site which was given to the ADCK by the municipality of Nouméa, is a thin peninsula which sticks out south into the blue lagoon. (It was here that Tjibaou had held the Melanesia 2000 festival in 1975, one of the key moments in the struggle for cultural and political recognition by France.) Early on in the programme for the centre, the indigenous bush was supplemented with transplanted Norfolk Island pines, those wonderful, stiff architectural trees which so gracefully articulate the sky-lines of the islands of the south-western Pacific.

From the first, Piano was concerned to learn from local culture, buildings and nature, but he was determined not to end up with a kitsch replication of Kanak huts. He took from them the ideas of the village cluster and the ribbed hut structure in which tall thin curved timber members cluster together at the top and carry the cladding. In the original vernacular, the ribs are of palm saplings; in Piano’s (much larger) reinterpretation of the forms, they are made of laminated iroko, structurally linked by horizontal tubes and diagonal rod ties of stainless steel. The happy and carefully crafted conjunction of stainless steel and laminated timber is reminiscent of the IBM pavilion which travelled Europe so successfully over a decade ago, but here the long wooden pieces are not so finely pared, partly because they are much bigger to achieve resistance to cyclones and earthquakes, and partly because they have to be tall to make a celebratory figure.

What Piano calls the ‘cases’, pavilions or abstracted huts, are of three heights, the tallest 28m, as high as an eight- or nine-storey urban building. They are arranged in three groups, the villages, in a very gently curving line that follows the axis of the peninsula. The cases are fundamentally circular in plan, but they open off a long connecting corridor, so the inner edge of each circle is honed off, allowing individual cases to lock into the connecting space, then beyond that into more conventional rectilinear volumes (sometimes but not always part of the spatial flow). Here, planted courts penetrate the building, the flat stainless steel and glass roofs are supported on laminated flitched iroko columns; volumes are largely defined by timber and glass louvres, which form part of the passive cooling system. To the north-west, there is a strip between the irregular edge of the building and the sea, densely planted and carved into with terraces and clearings for public extensions of the building as open-air exhibition and performance spaces. And for the pedestrian route round the peninsula’s perimeter which introduces visitors to the flora of the place and its mythic meanings, which are very powerful in Kanak culture.

Externally, the cases stretch their curves among and over the tall verticals and horizontals of the pines and eucalypts, making a heraldic dance against the sky which is partnered by reflections rippling in the lagoon. Piano hopes that the rot-proof iroko ribs will weather to the same pale silvery grey as the trunks of the indigenous palm trees. As well as being an abstracted hut, each case is a sort of forest. Each curved outer rib is linked to a straight vertical one which forms part of the structure of the perimeter of the enclosed space. The curved ribs carry horizontal slats, which have some effect on modifying the effects of the often high winds, and internal conditions are controlled by a passive system which uses louvres at the base of the perimeter wall and on the opposite face of the complex. They are opened and closed according to wind direction and intensity, encouraging breezes through the spaces from which air is expelled along the highest points of the roofs.

It has to be admitted that the curved ribs have a largely symbolic role, but they do have a climate balancing function: ‘I decided to tone down the resemblance between “my” huts and reducing the length of the vertical elements and giving the shells more open form ... the staves no longer meet at the top, as had initially been planned. The wind tunnel [showed] that this produced a greater effect of dynamic ventilation.’ Yet they have deeper resonances, some literal: the wind surging through the slats of the open outer carapace gives ‘the huts a “voice”: ... it is that of the Kanak villages and their forests’.

Marie Claude Tjibaou, who is the president of the ADKC, understands the mediatory role of the building: ‘Today, everyone is coming to see the architecture. Little by little, we will bring people to ask: why these arcs, why these vaults’. They will be instrumental in helping the Kanaks achieve her husband’s ambition of telling ‘the world that we are neither escapees from prehistory nor archaeological remains, but men of flesh and blood’.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment