Grave of Composer Luigi Nono

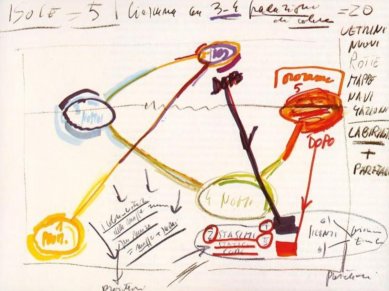

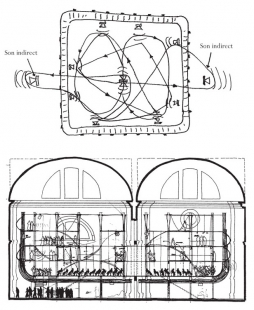

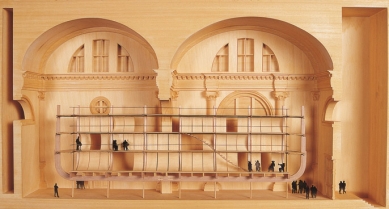

The life and work of one of the greatest Italian composers of the second half of the 20th century, Luigi Nono, is intrinsically linked to the city on the lagoon, where he is also buried in the ivy-covered grave at the island cemetery San Michele, marked by a gravestone from the Japanese postmodern architect Arata Isozaki. His minimalist compositions remain relevant even thirty years after Nono's death. Peter Zumthor admits that he does not follow the work of his colleagues, but in his Swiss studio, he exclusively listens to Nono's music, which is his greatest source of inspiration; he appreciates the stories hidden behind each composition and sees various layers in Nono's music that resemble architecture. Inspiration can come not only from the sound recording but also from its notation, which was not constrained by the black-and-white tradition of five-line staff paper. Nono's most famous collaboration with an architect was with the Genoese native Renzo Piano in designing the stage for the premiere of the opera Prometheus (Prometeo, tragedia dell’ascolto). Luigi Nono wrote this opera between 1981 and 1984, and the first version premiered on September 25, 1984, in the Venetian church of San Lorenzo, where the composer and architect also designed a stage reminiscent of a giant musical instrument, with wooden beams filled with plywood boards. The musicians stood at various levels around the perimeter to better resonate the boards, and the listeners were concentrated in the middle of the lower part of the temporary structure hovering in the church space. In addition to the unique listening experience, visitors also faced an unconventional walk up a staircase shaped like a sinusoid, where each step had a different height. Over a year after the Venetian premiere, the revised opera was performed in the industrial hall of the Ansaldo power company in Milan.

Luigi Nono was born on January 29, 1924, in Venice into a wealthy artistic family. From 1941, he studied at the Venice Conservatory Accademia di Musica Benedetto Marcello di Venezia. In 1942, he studied law at the University of Padua, which he successfully completed in 1946, and then began studying composition under Bruno Maderna. As part of the Venice Biennale in 1948, he attended a conducting course led by Hermann Scherchen, who later introduced him to the musical thinking of the Second Vienna School. In 1952, Nono joined the Italian Communist Party, in which he was active locally and nationally throughout his life. In 1955, he married Nuria Schönberg. They had two daughters, Silvia and Serena Bastian. Through his compositions, he attempted to spread his political ideas and ideals. He considered the texts of ultra-leftist philosophers and revolutionaries to be correct. His works addressed current world events— the Holocaust, nuclear wars, the alienation of the capitalist world, anti-fascist resistance. Thanks to his actions, Nono contributed to the naming of a program for schools dedicated to educating students toward tolerance, human rights, and European integration— the Nonoproject. He died after a prolonged liver illness in a Venice hospital on May 8, 1990. He is buried at the San Michele cemetery next to such giants as Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky, Sergei Diaghilev, and Ezra Pound.

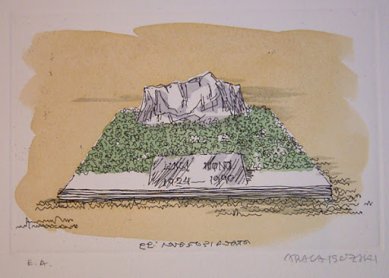

The architect of Nono's grave is the Japanese architect Arata Isozaki, who first introduced himself in Europe at the 14th Triennale in Milan, presenting the Electric Labyrinth, a revolutionary work conceived as a multimedia presentation of the Hiroshima tragedy, consisting of randomly rotating screens and images projected in reverse. With this work, he gained a reputation among the European avant-garde. His characteristic features include the use of unusual combinations of materials such as stone + metal + wood. His buildings are characterized by bold forms, solid, massive volumes, interesting colors, and inventiveness. He uses simple geometric shapes.

While writing this text, I could not help but listen to Nono's avant-garde work, which impressed me with its lightness and, at times, the impact of the realities with which Nono struggled in life. I have not seen his grave in person, so I quote New York music critic Alex Ross, who visited San Michele Island to pay tribute to the lives and works of great personalities, including Nono himself.

“Finally, after some minutes’ search, I found Luigi Nono, whose monument is beautiful and austere: a rough, irregular piece of rock at the head of ivy. Here, too, I placed a pebble, though the gesture seemed intrusively sentimental.”

To me, the grave gives off a calm impression, which unexpectedly yet justifiably disrupts the large stone (just like Nono's music), which, in my opinion, points to the composer’s lifelong struggle with the harsh realities of the 20th century. And then to the architect himself, whose work is directed by the philosophical ideas of the "new wave" of Japanese architects of the mid-20th century.*

*“They have come to the conviction that, currently, it is no longer possible to achieve a meaningful relationship between a building and the city as a whole; each building today is a solitary entity, and harmoniously incorporating it into the chaotic mix of a modern metropolis is not possible.”

Petr Šmídek

Luigi Nono was born on January 29, 1924, in Venice into a wealthy artistic family. From 1941, he studied at the Venice Conservatory Accademia di Musica Benedetto Marcello di Venezia. In 1942, he studied law at the University of Padua, which he successfully completed in 1946, and then began studying composition under Bruno Maderna. As part of the Venice Biennale in 1948, he attended a conducting course led by Hermann Scherchen, who later introduced him to the musical thinking of the Second Vienna School. In 1952, Nono joined the Italian Communist Party, in which he was active locally and nationally throughout his life. In 1955, he married Nuria Schönberg. They had two daughters, Silvia and Serena Bastian. Through his compositions, he attempted to spread his political ideas and ideals. He considered the texts of ultra-leftist philosophers and revolutionaries to be correct. His works addressed current world events— the Holocaust, nuclear wars, the alienation of the capitalist world, anti-fascist resistance. Thanks to his actions, Nono contributed to the naming of a program for schools dedicated to educating students toward tolerance, human rights, and European integration— the Nonoproject. He died after a prolonged liver illness in a Venice hospital on May 8, 1990. He is buried at the San Michele cemetery next to such giants as Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky, Sergei Diaghilev, and Ezra Pound.

The architect of Nono's grave is the Japanese architect Arata Isozaki, who first introduced himself in Europe at the 14th Triennale in Milan, presenting the Electric Labyrinth, a revolutionary work conceived as a multimedia presentation of the Hiroshima tragedy, consisting of randomly rotating screens and images projected in reverse. With this work, he gained a reputation among the European avant-garde. His characteristic features include the use of unusual combinations of materials such as stone + metal + wood. His buildings are characterized by bold forms, solid, massive volumes, interesting colors, and inventiveness. He uses simple geometric shapes.

While writing this text, I could not help but listen to Nono's avant-garde work, which impressed me with its lightness and, at times, the impact of the realities with which Nono struggled in life. I have not seen his grave in person, so I quote New York music critic Alex Ross, who visited San Michele Island to pay tribute to the lives and works of great personalities, including Nono himself.

“Finally, after some minutes’ search, I found Luigi Nono, whose monument is beautiful and austere: a rough, irregular piece of rock at the head of ivy. Here, too, I placed a pebble, though the gesture seemed intrusively sentimental.”

To me, the grave gives off a calm impression, which unexpectedly yet justifiably disrupts the large stone (just like Nono's music), which, in my opinion, points to the composer’s lifelong struggle with the harsh realities of the 20th century. And then to the architect himself, whose work is directed by the philosophical ideas of the "new wave" of Japanese architects of the mid-20th century.*

*“They have come to the conviction that, currently, it is no longer possible to achieve a meaningful relationship between a building and the city as a whole; each building today is a solitary entity, and harmoniously incorporating it into the chaotic mix of a modern metropolis is not possible.”

Ondřej Indruch

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment