Pael House

|

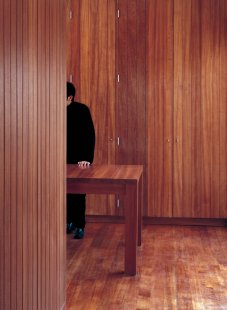

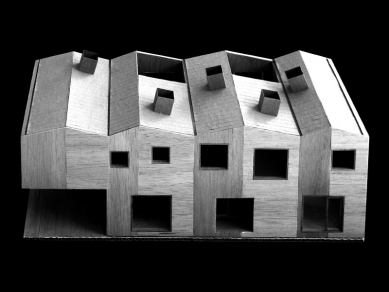

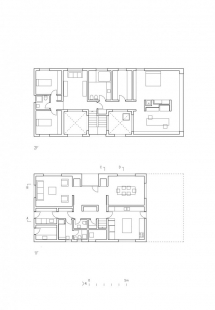

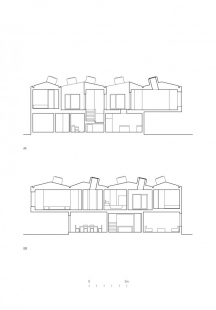

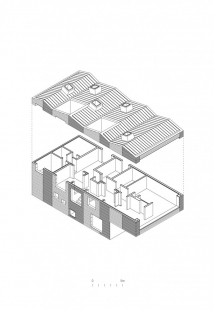

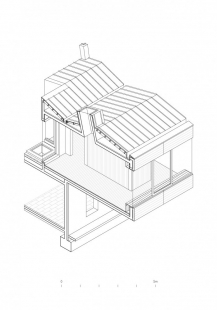

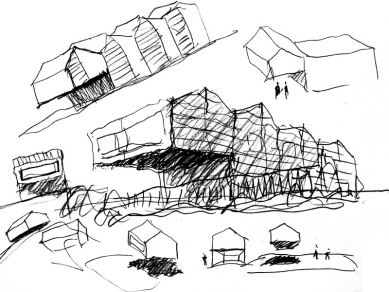

In an almost automatic move we proposed a heavy and clumsy rectangular prism that echoed the cornered site tucked away at the end of the street; we projected an extension of the plot in two elevated dry patios; we planned a piece that unified the silhouette of four pitched roofs, not too different from the naïve outlines of a child’s drawing; we built a secondary pigmented concrete wall that was repaired several times during its crafted fabrication and that was build in layers so that each new one spilled itself over the previous one. “It’s the weeping house” a carpenter said while he varnished the boards of the furniture “perhaps the only way to avoid aging is to be born old”. Of the four infantile silhouettes only the one closest to the street does not have a base. It is a transversal block suspended over the little remaining air offered by the neighborhood’s square.

When Colomina talks about Graham’s inbuilt project she teaches us that “since each house in the urbanization faces an almost identical one across the street, its window becomes another identification screen, a kind of mirror”. In this case, the mirror occupies a place unreachable to the direct eye. It is a disproportioned showcase that allows intruders to enter only when they look from a distance.

0 comments

add comment