<Dominus Winery>

I refuse to write about something I have never experienced up close with my own senses. I have been unlucky. Excursions take place every first Friday of the month. For the rest of the month, the owners wish to keep peace for themselves and their illegal employees from Mexico.

Let me briefly reflect on the harmfulness or usefulness of famous buildings to their owners:

We strive for buildings to be unique. For the architect's skills to grow with each realization. We do not want to repeat ourselves, and we do not want others to mimic us. Of everything built in the world, only one percent is worth looking at. And these buildings become potential victims of tourist attacks. For older objects, this can be regulated by declaring them urban, national, or world heritage sites, expelling original inhabitants, defining a corridor for tourists with a red rope, and completely preserving the rest. However, there are still functioning young buildings that have to face similar attacks. How must the relatives feel leaving the funeral parlor, where they last said goodbye to the deceased, with a full bus of architectural gawkers armed with cameras and lenses of all calibers in attendance? There have always been problems with religious buildings. The best architects built them. Cultural buildings followed. Nowadays, even employees of scientific laboratories and research institutes are losing their peace. In conclusion, I will mention the most glaring case where a building overshadowed its original purpose. Boubourg has become an icon. Most tourists ride the escalator up and down. They take photos on the slanted scene in front of the building and show little interest in what exhibition is currently taking place in this cultural factory.

However, to ensure you do not feel deprived of a verbal accompaniment to the winery, I am including a comment from Jacques Herzog:

Our client, the renowned winemaker Christian Moueix from Bordeaux, immediately recognized the quality of the Napa Valley region for grape growing compared to numerous places nearby. Upon researching the archives, he discovered that there used to be a Native American settlement here. At the vineyard known as Napanouk, excellent grapevines were produced as early as the beginning of the century. After decades of hard work on this land, Moueix created a very high-quality wine, Dominus, which garnered so much attention worldwide that he decided to build a winery for it.

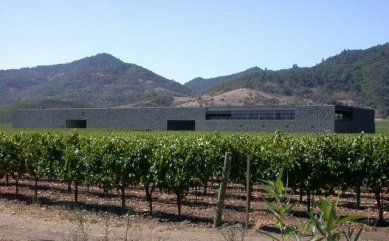

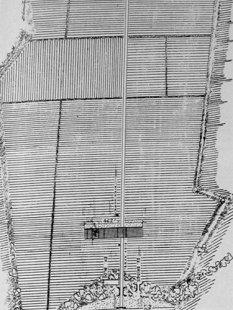

The building is divided into the following functional units: a room with huge chrome tanks for the first stage of fermentation, a cellar with oak barrels where the wine ages for two years, and finally a storage area where the wine is bottled, packaged, and stored. We designed a house that connects these three functional units into a linear building about 333 feet long, 82 feet wide, and 30 feet high. The building crosses the main axis; the main path of the winery is also the center of the vineyard. The grapevines grow to over 6 feet, so the building is completely integrated into the geometric linear texture of the vineyard.

On the ground floor, we divided the functional units with covered passages. The largest passage also serves as the main path of the vineyard. These enormous covered areas serve as public spaces where all the important parts of the vineyard connect with each other. From these areas, there is access to the aging cellars, tasting room, offices, and rooftop terraces, storage areas, and giant doors leading to the tank spaces. Guests are welcomed into the tasting room for wine tasting. A glass wall allows a view into the cellars with oak barrels. The last unit - the storage area, where boxes of wine are stored, lies to the south.

The climate in Napa Valley is extreme. It is very hot during the day and very cool at night. We wanted to design a structure that could take advantage of this fact. In the United States, air conditioning is automatically installed in most rooms. Architectural solutions that utilize walls to regulate temperature are unknown here.

In front of the facade, we placed "gabions" (wire baskets filled with stones), elements used in hydraulic engineering. By adding to the load-bearing walls, they created an inert mass that protects the rooms from the heat during the day and the cold at night. We chose local dark green to black basalt. The gabions were filled with varying densities, so some are almost impermeable while others allow light to pass into the passages: daylight flows into the rooms during the day, and at night, artificial light seeps through the stones outside. Our way of working with stone with varying degrees of transparency could be described as skin rather than traditional masonry.

Let me briefly reflect on the harmfulness or usefulness of famous buildings to their owners:

We strive for buildings to be unique. For the architect's skills to grow with each realization. We do not want to repeat ourselves, and we do not want others to mimic us. Of everything built in the world, only one percent is worth looking at. And these buildings become potential victims of tourist attacks. For older objects, this can be regulated by declaring them urban, national, or world heritage sites, expelling original inhabitants, defining a corridor for tourists with a red rope, and completely preserving the rest. However, there are still functioning young buildings that have to face similar attacks. How must the relatives feel leaving the funeral parlor, where they last said goodbye to the deceased, with a full bus of architectural gawkers armed with cameras and lenses of all calibers in attendance? There have always been problems with religious buildings. The best architects built them. Cultural buildings followed. Nowadays, even employees of scientific laboratories and research institutes are losing their peace. In conclusion, I will mention the most glaring case where a building overshadowed its original purpose. Boubourg has become an icon. Most tourists ride the escalator up and down. They take photos on the slanted scene in front of the building and show little interest in what exhibition is currently taking place in this cultural factory.

However, to ensure you do not feel deprived of a verbal accompaniment to the winery, I am including a comment from Jacques Herzog:

Our client, the renowned winemaker Christian Moueix from Bordeaux, immediately recognized the quality of the Napa Valley region for grape growing compared to numerous places nearby. Upon researching the archives, he discovered that there used to be a Native American settlement here. At the vineyard known as Napanouk, excellent grapevines were produced as early as the beginning of the century. After decades of hard work on this land, Moueix created a very high-quality wine, Dominus, which garnered so much attention worldwide that he decided to build a winery for it.

The building is divided into the following functional units: a room with huge chrome tanks for the first stage of fermentation, a cellar with oak barrels where the wine ages for two years, and finally a storage area where the wine is bottled, packaged, and stored. We designed a house that connects these three functional units into a linear building about 333 feet long, 82 feet wide, and 30 feet high. The building crosses the main axis; the main path of the winery is also the center of the vineyard. The grapevines grow to over 6 feet, so the building is completely integrated into the geometric linear texture of the vineyard.

On the ground floor, we divided the functional units with covered passages. The largest passage also serves as the main path of the vineyard. These enormous covered areas serve as public spaces where all the important parts of the vineyard connect with each other. From these areas, there is access to the aging cellars, tasting room, offices, and rooftop terraces, storage areas, and giant doors leading to the tank spaces. Guests are welcomed into the tasting room for wine tasting. A glass wall allows a view into the cellars with oak barrels. The last unit - the storage area, where boxes of wine are stored, lies to the south.

The climate in Napa Valley is extreme. It is very hot during the day and very cool at night. We wanted to design a structure that could take advantage of this fact. In the United States, air conditioning is automatically installed in most rooms. Architectural solutions that utilize walls to regulate temperature are unknown here.

In front of the facade, we placed "gabions" (wire baskets filled with stones), elements used in hydraulic engineering. By adding to the load-bearing walls, they created an inert mass that protects the rooms from the heat during the day and the cold at night. We chose local dark green to black basalt. The gabions were filled with varying densities, so some are almost impermeable while others allow light to pass into the passages: daylight flows into the rooms during the day, and at night, artificial light seeps through the stones outside. Our way of working with stone with varying degrees of transparency could be described as skin rather than traditional masonry.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment