Hradec Králové architect and urban planner Oldřich Liska

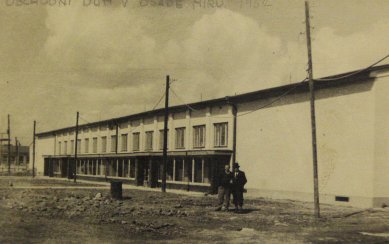

There are creators who etch themselves into the collective consciousness through collaboration on a grand common work. Among these exceptional works in the tradition of Czech modern architecture are undoubtedly two newly created urban centers - Hradec Králové and Zlín. In the case of Zlín, its emergence was aided by the dynamic growth of Baťa's factories; for Hradec Králové, the desire to transform a fortress town into a modern metropolis of Northeast Bohemia. This effort was embodied in the tireless work of JUDr. František Ulrich, the long-time mayor of the city and its ideological creator. Ulrich's ambitions led Hradec Králové to collaborate with J. Kotěra, J. Gočár, but also with the now less-known architect Oldřich Liska. However, it was precisely Oldřich Liska who, alongside Jan Kotěra and Josef Gočár, most significantly imprinted on the face of this city.

Oldřich Liska was born on April 17, 1881, in Kamhajk near Kolín. In 1899, he trained as a bricklayer at the Society of Construction and Artistic Crafts in Prague and later continued his studies at the State Industrial School in Prague. In 1901, he went to study at the School of Applied Arts in Dresden with Professor W. Meyer. He gained practical experience in the field between 1897 and 1902 with the construction firm of Matěj Blecha in Prague. After completing military service in 1905, he briefly practiced in Polička with the construction company Niklíček, but the following year he returned to Dresden, where he briefly became a project designer in H. Watzlavik's studio. The Dresden and later Munich period, as well as the entire then German architecture, initially had a strong impact on Liska. It was during his stay in Munich that Oldřich Liska likely met architect Ladislav Skřivánek, in whose Vienna studio he worked in 1908. The following year, as a designer for the construction firm of Josef Jihlavce, he came to Hradec Králové, where he briefly collaborated with architect Vladimír Fultner, a later proponent of cubist architecture. In the years 1910-1914, he was a co-owner of the design office Fňouk-builder & Liska-architect. In the post-war years, he was the chief designer of the Hradec Králové Construction Company and an employee of the municipal Technical Office. The desire to design his own architecture led O. Liska to the decision to establish his own studio, which between 1921 and 1950 became one of the most significant design offices in Northeast Bohemia. After World War II, the architect left the city and went to the war-destroyed Opava to participate in its reconstruction, first as a private designer and after the February coup as an employee of Stavoprojekt. Oldřich Liska died on December 8, 1959, in Brno.

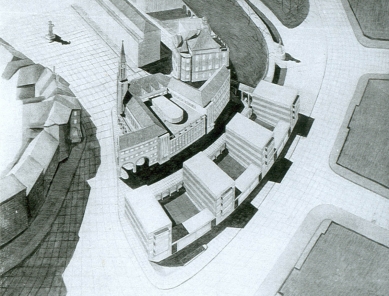

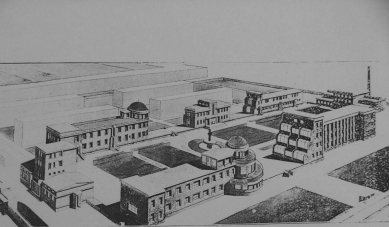

In 1909, at the initiative of F. Ulrich, a competition was announced for a new regulatory plan for Hradec Králové, which aimed to establish firm principles for the city's development. The first prize went to the work of engineers Vladimír Zákrejs, Josef Šejna, and Václav Rejchl, while the plan "Liberation" by Oldřich Liska and MUDr. Otakar Klumpar was awarded second place. It brought new ideas for the modification and utilization of the right bank of the Elbe basin, which, after the regulation of the Elbe banks carried out between 1907 and 1911, represented an ideal space for the construction expansion of the newly envisioned urban center. On the recommendation of Jan Kotěra, in 1911, Oldřich Liska and Václav Rejchl were commissioned to develop the final regulatory plan. Their concept built upon an earlier urbanist scheme from 1890, utilized the already existing square located in front of Kotěra's bridge, and linked to three existing communication radii radiating from this area. The main idea of the plan was to create a new cohesive urban core serving the cultural needs of the city. In the center of the square, where the axis of the new boulevard ran, a new theater was to be built. This would create a significant point of view. Other urban districts, which were partly interconnected by a radial circular system, were systematically divided according to their functions and evenly distributed around the historical core of the city. In 1911, the German magazine Der Städtebau responded positively to the progress of the Hradec Králové urbanists(1).

After stagnation caused by World War I, Ulrich's leadership of the city recognized the necessity of newly addressing the development of the future Hradec Králové agglomeration. Therefore, in 1919, it commissioned Oldřich Liska to develop a new concept for Hradec Králové. Liska reassessed his pre-war plan and presented to some extent a utopian vision of the so-called Great Hradec Králové, which anticipated the administrative merger of Hradec Králové with its 11 nearest municipalities into a whole for 35,000 inhabitants, interconnected by a road and rail circuit. One of the most significant ideas of the plan was the effort to create hygienically acceptable living spaces, which represented open building blocks adorned with greenery. Many of the prompts that Liska's plans brought to the city were later re-evaluated and adjusted by Josef Gočár, the author of the new regulations emerging after 1925. These were primarily related to the new Ulrich Square, which, despite Liska's original intention, became the financial center of the city.

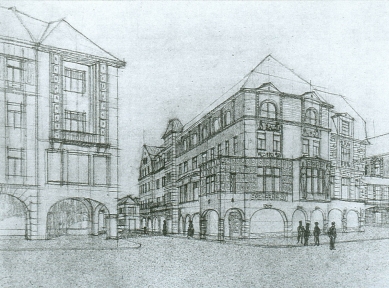

Oldřich Liska belonged to the generation of architects who had the opportunity to participate in the process of the radical transformation of decorative architecture into utilitarian and functional construction. Therefore, in his work, one can observe not only the lingering spirit of modernity, cubizing decorativism, machinist and purist tendencies, but also functionalism, albeit in a more moderate and classicizing form. Early sketches and photographs of clay models, on which the architect created a real spatial concept and verified their impact in the context of already existing architecture, evoke the impression that Liska was a decorativist whose intention was to create an aesthetically appealing Gesamtkunstwerk based on the tradition of classicism and German secession. These tendencies were most evident in the monumentality and symmetrical dispositions of unrealized buildings from his first regulatory plan from 1909, and we can also find them in Liska's otherwise self-contained architecture from the early twenties. It was perhaps the engagement in Hradec Králové with Jihlavc's construction firm that, at the beginning of the second decade, led the young artist to architecture close to the "Kotěra" style. This significant Hradec firm indeed executed the project for Kotěra's museum between 1909 and 1912. One of the first "Kotěra-style" projects by Oldřich Liska was the design for the Loan and Credit Bank from the 1910 competition, or the realization of the now non-existent automobile garages of ing. J. Novák from 1911 in Hradec Králové.

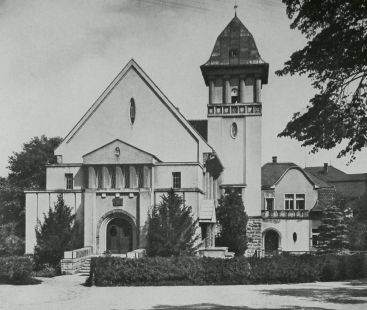

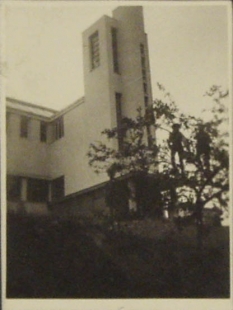

The following year, Liska's first significant architecture in Hradec Králové was completed, the Protestant church with a rectory (Komenského č.p. 529). In it, there was a shift in the architect's thinking. Liska loosened the previously used symmetrical layout, evidently under the influence of Kotěra's museum, limited the expression of the facade to a minimum, and changed the type of floral decor that had previously been used.

Another significant milestone was the collaboration with the prominent Hradec Králové architect, the aforementioned Vladimír Fultner, with whom Liska developed a competition design for the unrealized administrative building of the General Credit Association in Hradec Králové in 1910. Later, Liska had the opportunity to collaborate with Fultner on the realization of the villa of Otakar and Karla Čerych in Jaroměř (Lužická čp. 321) from 1913. In the architecture of this building, Fultner's cubist thinking emerged, influenced by the circle of Pavla Janáka and Josef Gočár. However, Liska never reached the cubist mass of architecture in the sense of Janák's theses. In his thinking, cubism and its crystalline structure meant only a merely decorative novelty in the articulation of facades and fronts of buildings (residential houses from 1913 on Masaryk Square č.p. 527, 536, 538 or the Protestant church in Pečka from 1914).

After the end of World War I and the establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic, Liska's architectural language changed once again. In the early years of this period, one can still observe the lingering cubist decor, particularly evident on the large block of residential buildings for the employees of the ČSD directorate from 1919-1921 (Klumparova č.p. 565-567, 571-573), but otherwise, Liska had already established his specific and unmistakable signature. This was first manifested in the competition project for the complex of the new district hospital in Hradec Králové from 1923. The constructively conceived and puristically smoothly molded masses of the buildings of individual pavilions reflected the need for low construction and operational costs and suitable spaces intended for the individual departments, as the resultant language of Liska's architecture is always a logical reaction, a result whose initial impulse becomes the purpose for which the final building is to serve. Therefore, Liska used his later favored machinist elements - metal aerodynamic arched windows, which provided operating rooms with ample natural light. And it was precisely this motif, arising partly under the influence of German expressionists, partly under the influence of the technical euphoria of the 1920s, symbolized by the rounded hood of a car, that became Liska's specific structural feature, used throughout the third decade, especially in projects for school buildings but also for family homes.

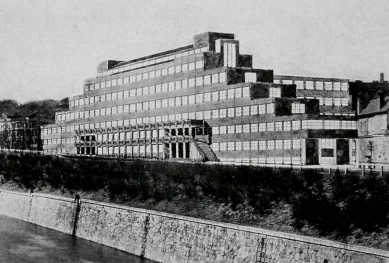

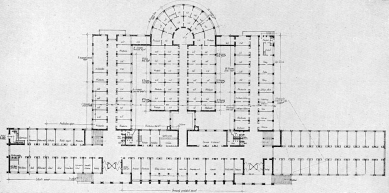

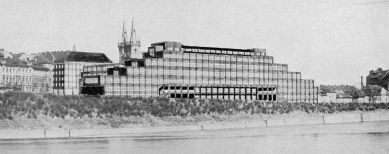

In 1924, one of the key architectural competitions of that time took place, the competition for the Accident Insurance for Workers in Prague. The significance of the competition was enhanced by the participation of Jaromír Krejcar and František M. Černý and their clash with the more conservative wing of architects. Liska presented a work close to the more radical proponents - an axially oriented, constructivistically austere layout, with volumes divided only by horizontal strips of windows, in the plan of a double letter T. The leading idea of the proposal became the aim to achieve: "1. Completely clear orientation within the extensive building across all its sections. 2. To achieve direct lighting in all offices while eliminating enclosed courtyards." (2) Liska's proposal received the highest accolade and was recommended for implementation. Unfortunately, this did not happen. Although it was merely a project, Oldřich Liska reached the peak of his creative powers with it and created a project that Karel Teige described as "...truly the best project in this competition."(3) The architectural and floor plan qualities were appreciated, in hindsight, also by one of the participants of the competition, architect Karel Honzík, who wrote: "Today we must truly go back and appreciate the high merits of Liska's proposal..."(4)

In the years 1926-1927, Liska realized his best villa construction of the 1920s, the house of Rudolf Háska in Jablonec nad Nisou. A simple cubus, executed in bare brick with a terrace, closed with an arched window of aerodynamic metal construction, thereby practically verifying the effect of bare brick, which he had planned in his competition proposal for municipal and general schools in Hradec Králové back in 1925.

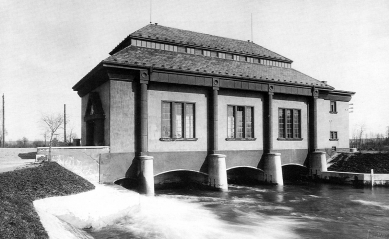

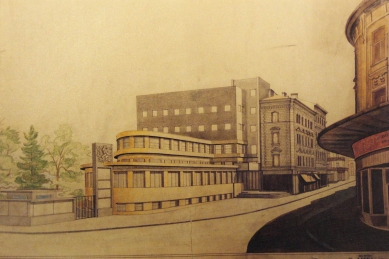

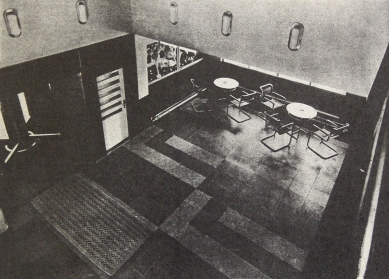

In 1928, on the occasion of the establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic, the board of the Hradec Králové Savings Bank decided to construct public municipal baths with a swimming pool at its own cost and entrusted the project to Oldřich Liska. The architect primarily recognized the social mission of this institution and therefore chose functionalism as the most appropriate language. Between 1928 and 1933, when the baths were opened to the public, he gradually developed three variants. The first two accounted for high investment costs and represented a generous functionalist architecture of asymmetrical floor plans, referring to the nautical language in the sense of Krejcar's architecture of "transatlantic liners." As a result of the global economic crisis, Liska was forced to revise the original study into a reduced version (1931) and significantly reduce investment expenditures. Nevertheless, he managed to create a quality project, which he developed based on careful studies of existing baths in Czechoslovakia, Germany, and Austria (Eliščino nábřeží č.p. 842).

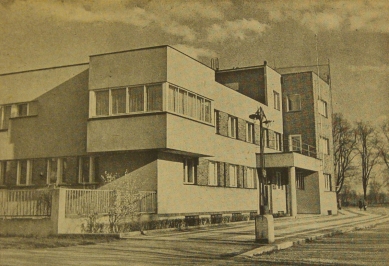

At the beginning of the 1930s, when the architect was at the peak of his creative powers, he realized two significant villa constructions in Hradec Králové. The house of A. Švorčík (Střelecká č.p. 832) and in its immediate vicinity, his own villa with a studio and design office (Střelecká č.p. 824), both from 1932. Liska contextually connected to the curved communication of the second city ring and applied a cultivated language of organic functionalism. He divided the building with continuous strip windows and added an antikizing peristyle with a pool to the garden wing. He imparted an inimitable character to his villa, which is far from Le Corbusier's idea of a house as a "machine for living." It is also worth mentioning the unrealized functionalist project for the buildings of district and financial offices from 1931.

The last important theme of Liska's work was a long-standing effort to conceive a new layout type for school buildings. Instead of the classic, hallway layout, Oldřich Liska introduced the concept of the so-called hall school, which he first presented in 1922 in a competition proposal for an Industrial School in Kutná Hora. However, Liska's hall school was realized only a decade later when it was built in Černilov near Hradec Králové in 1931. Oldřich Liska summarized the Černilov hall school with the words: "The new type of school with a central hall without corridors best suits modern teaching. In the central hall, school celebrations, lectures, theater performances, listening to the school radio, teaching by means of films, and corrective exercises during breaks take place, serving recreation, and exhibitions are held. The entrance features passing cloakrooms with washrooms. The building is cheaper than that of the corridor type school." (5)

1) Anonym. Zwei Wettbewerbsentwürfe zu einem Verbauungsplan für Königgrätz in Böhmen. Der Städtebau, 1911, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 13-16.

2) See the author's archive, Protocol of the Jury's Meeting to Assess Competition Proposals for the New Building of the Central Building of the Accident Insurance for Workers for Bohemia in Prague 1924.

3) Teige, K. The Work of Jaromír Krejcar. 1st ed. Prague: Václav Petr 1932, p. 52.

4) Honzík, K. Architecture Critique Between the Two World Wars. Czechoslovak Architect, 1961, vol. 7, no. 6, p. 8.

5) Liska, Oldřich. New Type of School Building. In Hradec Králové and Its Surroundings. Třebechovice pod Orebem. Dvůr Králové nad Labem. 1st ed. Prague: Nakl. Service des Pays 1932, p.

Oldřich Liska was born on April 17, 1881, in Kamhajk near Kolín. In 1899, he trained as a bricklayer at the Society of Construction and Artistic Crafts in Prague and later continued his studies at the State Industrial School in Prague. In 1901, he went to study at the School of Applied Arts in Dresden with Professor W. Meyer. He gained practical experience in the field between 1897 and 1902 with the construction firm of Matěj Blecha in Prague. After completing military service in 1905, he briefly practiced in Polička with the construction company Niklíček, but the following year he returned to Dresden, where he briefly became a project designer in H. Watzlavik's studio. The Dresden and later Munich period, as well as the entire then German architecture, initially had a strong impact on Liska. It was during his stay in Munich that Oldřich Liska likely met architect Ladislav Skřivánek, in whose Vienna studio he worked in 1908. The following year, as a designer for the construction firm of Josef Jihlavce, he came to Hradec Králové, where he briefly collaborated with architect Vladimír Fultner, a later proponent of cubist architecture. In the years 1910-1914, he was a co-owner of the design office Fňouk-builder & Liska-architect. In the post-war years, he was the chief designer of the Hradec Králové Construction Company and an employee of the municipal Technical Office. The desire to design his own architecture led O. Liska to the decision to establish his own studio, which between 1921 and 1950 became one of the most significant design offices in Northeast Bohemia. After World War II, the architect left the city and went to the war-destroyed Opava to participate in its reconstruction, first as a private designer and after the February coup as an employee of Stavoprojekt. Oldřich Liska died on December 8, 1959, in Brno.

In 1909, at the initiative of F. Ulrich, a competition was announced for a new regulatory plan for Hradec Králové, which aimed to establish firm principles for the city's development. The first prize went to the work of engineers Vladimír Zákrejs, Josef Šejna, and Václav Rejchl, while the plan "Liberation" by Oldřich Liska and MUDr. Otakar Klumpar was awarded second place. It brought new ideas for the modification and utilization of the right bank of the Elbe basin, which, after the regulation of the Elbe banks carried out between 1907 and 1911, represented an ideal space for the construction expansion of the newly envisioned urban center. On the recommendation of Jan Kotěra, in 1911, Oldřich Liska and Václav Rejchl were commissioned to develop the final regulatory plan. Their concept built upon an earlier urbanist scheme from 1890, utilized the already existing square located in front of Kotěra's bridge, and linked to three existing communication radii radiating from this area. The main idea of the plan was to create a new cohesive urban core serving the cultural needs of the city. In the center of the square, where the axis of the new boulevard ran, a new theater was to be built. This would create a significant point of view. Other urban districts, which were partly interconnected by a radial circular system, were systematically divided according to their functions and evenly distributed around the historical core of the city. In 1911, the German magazine Der Städtebau responded positively to the progress of the Hradec Králové urbanists(1).

After stagnation caused by World War I, Ulrich's leadership of the city recognized the necessity of newly addressing the development of the future Hradec Králové agglomeration. Therefore, in 1919, it commissioned Oldřich Liska to develop a new concept for Hradec Králové. Liska reassessed his pre-war plan and presented to some extent a utopian vision of the so-called Great Hradec Králové, which anticipated the administrative merger of Hradec Králové with its 11 nearest municipalities into a whole for 35,000 inhabitants, interconnected by a road and rail circuit. One of the most significant ideas of the plan was the effort to create hygienically acceptable living spaces, which represented open building blocks adorned with greenery. Many of the prompts that Liska's plans brought to the city were later re-evaluated and adjusted by Josef Gočár, the author of the new regulations emerging after 1925. These were primarily related to the new Ulrich Square, which, despite Liska's original intention, became the financial center of the city.

Oldřich Liska belonged to the generation of architects who had the opportunity to participate in the process of the radical transformation of decorative architecture into utilitarian and functional construction. Therefore, in his work, one can observe not only the lingering spirit of modernity, cubizing decorativism, machinist and purist tendencies, but also functionalism, albeit in a more moderate and classicizing form. Early sketches and photographs of clay models, on which the architect created a real spatial concept and verified their impact in the context of already existing architecture, evoke the impression that Liska was a decorativist whose intention was to create an aesthetically appealing Gesamtkunstwerk based on the tradition of classicism and German secession. These tendencies were most evident in the monumentality and symmetrical dispositions of unrealized buildings from his first regulatory plan from 1909, and we can also find them in Liska's otherwise self-contained architecture from the early twenties. It was perhaps the engagement in Hradec Králové with Jihlavc's construction firm that, at the beginning of the second decade, led the young artist to architecture close to the "Kotěra" style. This significant Hradec firm indeed executed the project for Kotěra's museum between 1909 and 1912. One of the first "Kotěra-style" projects by Oldřich Liska was the design for the Loan and Credit Bank from the 1910 competition, or the realization of the now non-existent automobile garages of ing. J. Novák from 1911 in Hradec Králové.

The following year, Liska's first significant architecture in Hradec Králové was completed, the Protestant church with a rectory (Komenského č.p. 529). In it, there was a shift in the architect's thinking. Liska loosened the previously used symmetrical layout, evidently under the influence of Kotěra's museum, limited the expression of the facade to a minimum, and changed the type of floral decor that had previously been used.

Another significant milestone was the collaboration with the prominent Hradec Králové architect, the aforementioned Vladimír Fultner, with whom Liska developed a competition design for the unrealized administrative building of the General Credit Association in Hradec Králové in 1910. Later, Liska had the opportunity to collaborate with Fultner on the realization of the villa of Otakar and Karla Čerych in Jaroměř (Lužická čp. 321) from 1913. In the architecture of this building, Fultner's cubist thinking emerged, influenced by the circle of Pavla Janáka and Josef Gočár. However, Liska never reached the cubist mass of architecture in the sense of Janák's theses. In his thinking, cubism and its crystalline structure meant only a merely decorative novelty in the articulation of facades and fronts of buildings (residential houses from 1913 on Masaryk Square č.p. 527, 536, 538 or the Protestant church in Pečka from 1914).

After the end of World War I and the establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic, Liska's architectural language changed once again. In the early years of this period, one can still observe the lingering cubist decor, particularly evident on the large block of residential buildings for the employees of the ČSD directorate from 1919-1921 (Klumparova č.p. 565-567, 571-573), but otherwise, Liska had already established his specific and unmistakable signature. This was first manifested in the competition project for the complex of the new district hospital in Hradec Králové from 1923. The constructively conceived and puristically smoothly molded masses of the buildings of individual pavilions reflected the need for low construction and operational costs and suitable spaces intended for the individual departments, as the resultant language of Liska's architecture is always a logical reaction, a result whose initial impulse becomes the purpose for which the final building is to serve. Therefore, Liska used his later favored machinist elements - metal aerodynamic arched windows, which provided operating rooms with ample natural light. And it was precisely this motif, arising partly under the influence of German expressionists, partly under the influence of the technical euphoria of the 1920s, symbolized by the rounded hood of a car, that became Liska's specific structural feature, used throughout the third decade, especially in projects for school buildings but also for family homes.

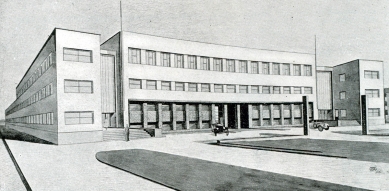

In 1924, one of the key architectural competitions of that time took place, the competition for the Accident Insurance for Workers in Prague. The significance of the competition was enhanced by the participation of Jaromír Krejcar and František M. Černý and their clash with the more conservative wing of architects. Liska presented a work close to the more radical proponents - an axially oriented, constructivistically austere layout, with volumes divided only by horizontal strips of windows, in the plan of a double letter T. The leading idea of the proposal became the aim to achieve: "1. Completely clear orientation within the extensive building across all its sections. 2. To achieve direct lighting in all offices while eliminating enclosed courtyards." (2) Liska's proposal received the highest accolade and was recommended for implementation. Unfortunately, this did not happen. Although it was merely a project, Oldřich Liska reached the peak of his creative powers with it and created a project that Karel Teige described as "...truly the best project in this competition."(3) The architectural and floor plan qualities were appreciated, in hindsight, also by one of the participants of the competition, architect Karel Honzík, who wrote: "Today we must truly go back and appreciate the high merits of Liska's proposal..."(4)

In the years 1926-1927, Liska realized his best villa construction of the 1920s, the house of Rudolf Háska in Jablonec nad Nisou. A simple cubus, executed in bare brick with a terrace, closed with an arched window of aerodynamic metal construction, thereby practically verifying the effect of bare brick, which he had planned in his competition proposal for municipal and general schools in Hradec Králové back in 1925.

In 1928, on the occasion of the establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic, the board of the Hradec Králové Savings Bank decided to construct public municipal baths with a swimming pool at its own cost and entrusted the project to Oldřich Liska. The architect primarily recognized the social mission of this institution and therefore chose functionalism as the most appropriate language. Between 1928 and 1933, when the baths were opened to the public, he gradually developed three variants. The first two accounted for high investment costs and represented a generous functionalist architecture of asymmetrical floor plans, referring to the nautical language in the sense of Krejcar's architecture of "transatlantic liners." As a result of the global economic crisis, Liska was forced to revise the original study into a reduced version (1931) and significantly reduce investment expenditures. Nevertheless, he managed to create a quality project, which he developed based on careful studies of existing baths in Czechoslovakia, Germany, and Austria (Eliščino nábřeží č.p. 842).

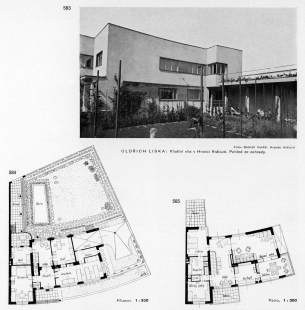

At the beginning of the 1930s, when the architect was at the peak of his creative powers, he realized two significant villa constructions in Hradec Králové. The house of A. Švorčík (Střelecká č.p. 832) and in its immediate vicinity, his own villa with a studio and design office (Střelecká č.p. 824), both from 1932. Liska contextually connected to the curved communication of the second city ring and applied a cultivated language of organic functionalism. He divided the building with continuous strip windows and added an antikizing peristyle with a pool to the garden wing. He imparted an inimitable character to his villa, which is far from Le Corbusier's idea of a house as a "machine for living." It is also worth mentioning the unrealized functionalist project for the buildings of district and financial offices from 1931.

The last important theme of Liska's work was a long-standing effort to conceive a new layout type for school buildings. Instead of the classic, hallway layout, Oldřich Liska introduced the concept of the so-called hall school, which he first presented in 1922 in a competition proposal for an Industrial School in Kutná Hora. However, Liska's hall school was realized only a decade later when it was built in Černilov near Hradec Králové in 1931. Oldřich Liska summarized the Černilov hall school with the words: "The new type of school with a central hall without corridors best suits modern teaching. In the central hall, school celebrations, lectures, theater performances, listening to the school radio, teaching by means of films, and corrective exercises during breaks take place, serving recreation, and exhibitions are held. The entrance features passing cloakrooms with washrooms. The building is cheaper than that of the corridor type school." (5)

1) Anonym. Zwei Wettbewerbsentwürfe zu einem Verbauungsplan für Königgrätz in Böhmen. Der Städtebau, 1911, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 13-16.

2) See the author's archive, Protocol of the Jury's Meeting to Assess Competition Proposals for the New Building of the Central Building of the Accident Insurance for Workers for Bohemia in Prague 1924.

3) Teige, K. The Work of Jaromír Krejcar. 1st ed. Prague: Václav Petr 1932, p. 52.

4) Honzík, K. Architecture Critique Between the Two World Wars. Czechoslovak Architect, 1961, vol. 7, no. 6, p. 8.

5) Liska, Oldřich. New Type of School Building. In Hradec Králové and Its Surroundings. Třebechovice pod Orebem. Dvůr Králové nad Labem. 1st ed. Prague: Nakl. Service des Pays 1932, p.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment