|

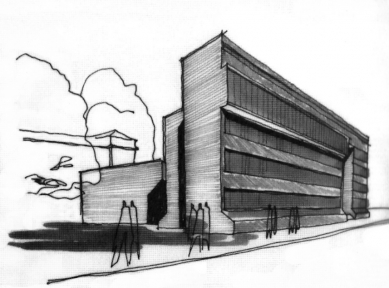

| E.Přikryl, Uran Shopping Center, 1980-83 |

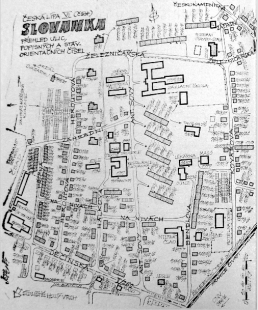

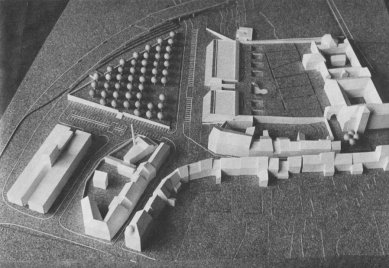

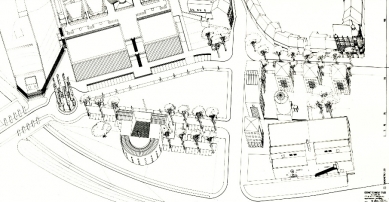

Particular attention is given in the text to the period from the 1970s to the 1980s. During this time, the uranium industry rapidly developed in Česká Lípa and throughout the region. In this golden era of the city, there was a significant increase in investment construction, primarily of apartment buildings for the influx of employees from the uranium mines. Unfortunately, the dynamic pace of the city's growth brought with it the destructive clearance of the original urban development. The new face of "uranium" Česká Lípa was shaped by quality public buildings from members of the Sial studio (Sever Primary School by Zdeněk Zavřel and Dalibor Vokáč, the District Committee building of the Communist Party by Otakar Binár, Uran Shopping Center by Emil Přikryl, and the Crystal Cultural House by Jiří Suchomel). Přikryl's shopping center (1980-1983) thoughtfully connected contemporary European architectural styles, new functionalism with postmodernism. The high value of Přikryl's department store has already been highlighted by Jan Sapák, Rostislav Švácha, and Petr Kratochvíl. Jiří Suchomel in the design of the cultural house (1974-1990) pioneeringly experimented with an unusual heating method at that time, using solar energy. Although the citizens of the city never accepted these buildings, they belong to the most valuable monuments of Czechoslovak architectural creation of the past regime.