Architecture of Contemporary Libraries – A Work in a State of Birth

Monika Mitášová

This text was published in the collection "library and architecture 2003 \ libraries without barriers", from which we were able to draw with the author's consent.

"If there is a theme that must attract the architect and simultaneously stimulate his wit and ingenuity, then it is the project of a public library." \Étienne-Louis Boullée, architect of the unrealized project of the French Royal Library from 1784

"I believe we live in a moment when our experience of the world is much less the experience of a long life developing over time than the experience of a network that connects points and weaves through its own tissue." \Michel Foucault, 1966

"Today everyone creates the impression, and also creates it in themselves, that within them they carry a book – if only because they have work, family, sick parents, a grumpy boss. A kind of story... We forget that literature demands from each of us a special way of discovery and effort, a certain creative intention attainable only through literature as such, whose role is in no way to record the immediate results of various activities and intentions. Books become 'secondary' where marketing takes precedence." \Gilles Deleuze, 1992

The turn of the 20th to the 21st century may be characterized, among many other events, by a cultural development that we generally consider another crisis and at the same time a transformation of European book culture. A kind of 'end' of the book and a 'new return' to the book. While skeptics at the turn of the century proclaimed the disappearance of the classical book from the European cultural tradition of books, the comforters, on the contrary, pointed to the growing interest in writing and reading both classical and non-classical books, accompanied by the care of publishing houses for both printed and electronically published and disseminated books. The increasing availability and wide response to the still cheaper dissemination of books on electronic media, production of inexpensive prints in large quantities and soft bindings, as well as the creation of rare books: bibliophilia published in small quantities, on quality paper, with thought-provoking typography, layout, binding, and illustrations, received significant criticism. Books that had been so often rejected and once again demanded were written, published, read, and commented on with new energy during the turn of the century. Their influence was manifested not only within professional communities but also in the interstitial areas of our knowledge. Books once again became the subject of groundbreaking visual, architectural, philosophical, and scientific works of recent times. Thinking turned to the tradition of writing and interpretation of book texts not only as one of its leading themes but also as a specific cognitive, critical, and creative performance. Europeans at the turn of the century read the world again as a book, an open work, a text without beginning and end – and conversely – they were once again happy to read the book as an image of a creative and interpretation-open world. Paradoxically, the very thing that skeptics of the turn of the century identified as the source and main culprit of the millennial death of the book contributed to this process – namely, the electronic and digital technologies of recording, dissemination, and reading data books and libraries. However, virtual books and libraries appear to be the transformative force that changes the classical and modern 'book' paradigm into a contemporary paradigm.

Electronic technologies influence not only the creation and management of private libraries and book archives but also the emergence and nature of public libraries. On the one hand, they give rise to a standalone type of public

library in the electronic environment (e-library), and on the other hand, they affect the organization, operation, and mutual connections of physical libraries. Today's public libraries with combined collections of paper, audiovisual, and virtual 'books' are now visited by readers faithful to print and those who prefer their newly acquired electronic literacy, as well as those who combine these qualities into a new quality: a type of "surfing" the electronic data, captivated also by the charm of printed paper. These friends of hybrid, physical-virtual libraries and virtually-current reading take both a computer mouse and (with a bit of luck) books and printed materials in their hands, which they have discovered in the library themselves and/or with the help of others or have stumbled upon. The modern library thus transforms, similarly to modern books and their readers, into a more complex, multi-component institution: it enables new, electronic ways of targeted and random searches for virtual texts and does not abandon the age-old opportunity for concentration, study, and exploration of both well-known and newly discovered beautiful, scholarly books and periodicals. It permits solitude as well as companionship while reading texts that bear on their paper bodies the traces of reading, and do not bear on their virtual bodies such traces. Contemporary libraries therefore distance us from browsing index cards and searching through physical records rather than from books themselves. Computers promise us books rather than taking them away from us.

They evoke hope that we may ultimately trace the long-desired paper books in libraries, and moreover – that we may find them in many unexpected meaningful contexts, networks of relationships, contexts and contexts of these contexts... Current electronic means may thus contribute not only as auxiliary and supportive elements modernizing already established traditional types of libraries but may also influence the design and creation of other libraries. Our telematic experience need not only be added additively and ex post to an already known space of reading, as some technological necessary evil, from which there is no escape, but it also has a chance to become a topic and creative approach of architecture, just like writing and reading classic books. Thinking about the architecture of contemporary libraries therefore represents for me a web developed in several different directions, among which I do not want, cannot, and will not judge. This will surely be taken up by others more eagerly and much better shortly. My role is different: I would now like to walk with you purposefully and randomly through a few of the many contemporary foreign libraries that I consider inspiring because they successfully capture the nature of the contemporary relationship of readers to books, reading, collecting, and borrowing books architecturally. Along with them, I will also pause at several inspiring projects and design processes of those libraries that were, for various reasons, not constructed or are currently under construction. We will now become, for a moment, not only readers of books but also readers of libraries. With a bit of patience, we may succeed. I would also like to ask in this context, in what sense are the mentioned libraries closed and/or open works of contemporary architecture: What inspires the meeting with readers of both physical and virtual books and how do they themselves become inspiring for these meetings?

|

| Unrealized project of Bibliothèque royale by Étienne-Louis Boullee (1784). |

"I believe we live in a moment when our experience of the world is much less the experience of a long life developing over time than the experience of a network that connects points and weaves through its own tissue." \Michel Foucault, 1966

"Today everyone creates the impression, and also creates it in themselves, that within them they carry a book – if only because they have work, family, sick parents, a grumpy boss. A kind of story... We forget that literature demands from each of us a special way of discovery and effort, a certain creative intention attainable only through literature as such, whose role is in no way to record the immediate results of various activities and intentions. Books become 'secondary' where marketing takes precedence." \Gilles Deleuze, 1992

The turn of the 20th to the 21st century may be characterized, among many other events, by a cultural development that we generally consider another crisis and at the same time a transformation of European book culture. A kind of 'end' of the book and a 'new return' to the book. While skeptics at the turn of the century proclaimed the disappearance of the classical book from the European cultural tradition of books, the comforters, on the contrary, pointed to the growing interest in writing and reading both classical and non-classical books, accompanied by the care of publishing houses for both printed and electronically published and disseminated books. The increasing availability and wide response to the still cheaper dissemination of books on electronic media, production of inexpensive prints in large quantities and soft bindings, as well as the creation of rare books: bibliophilia published in small quantities, on quality paper, with thought-provoking typography, layout, binding, and illustrations, received significant criticism. Books that had been so often rejected and once again demanded were written, published, read, and commented on with new energy during the turn of the century. Their influence was manifested not only within professional communities but also in the interstitial areas of our knowledge. Books once again became the subject of groundbreaking visual, architectural, philosophical, and scientific works of recent times. Thinking turned to the tradition of writing and interpretation of book texts not only as one of its leading themes but also as a specific cognitive, critical, and creative performance. Europeans at the turn of the century read the world again as a book, an open work, a text without beginning and end – and conversely – they were once again happy to read the book as an image of a creative and interpretation-open world. Paradoxically, the very thing that skeptics of the turn of the century identified as the source and main culprit of the millennial death of the book contributed to this process – namely, the electronic and digital technologies of recording, dissemination, and reading data books and libraries. However, virtual books and libraries appear to be the transformative force that changes the classical and modern 'book' paradigm into a contemporary paradigm.

Electronic technologies influence not only the creation and management of private libraries and book archives but also the emergence and nature of public libraries. On the one hand, they give rise to a standalone type of public

library in the electronic environment (e-library), and on the other hand, they affect the organization, operation, and mutual connections of physical libraries. Today's public libraries with combined collections of paper, audiovisual, and virtual 'books' are now visited by readers faithful to print and those who prefer their newly acquired electronic literacy, as well as those who combine these qualities into a new quality: a type of "surfing" the electronic data, captivated also by the charm of printed paper. These friends of hybrid, physical-virtual libraries and virtually-current reading take both a computer mouse and (with a bit of luck) books and printed materials in their hands, which they have discovered in the library themselves and/or with the help of others or have stumbled upon. The modern library thus transforms, similarly to modern books and their readers, into a more complex, multi-component institution: it enables new, electronic ways of targeted and random searches for virtual texts and does not abandon the age-old opportunity for concentration, study, and exploration of both well-known and newly discovered beautiful, scholarly books and periodicals. It permits solitude as well as companionship while reading texts that bear on their paper bodies the traces of reading, and do not bear on their virtual bodies such traces. Contemporary libraries therefore distance us from browsing index cards and searching through physical records rather than from books themselves. Computers promise us books rather than taking them away from us.

They evoke hope that we may ultimately trace the long-desired paper books in libraries, and moreover – that we may find them in many unexpected meaningful contexts, networks of relationships, contexts and contexts of these contexts... Current electronic means may thus contribute not only as auxiliary and supportive elements modernizing already established traditional types of libraries but may also influence the design and creation of other libraries. Our telematic experience need not only be added additively and ex post to an already known space of reading, as some technological necessary evil, from which there is no escape, but it also has a chance to become a topic and creative approach of architecture, just like writing and reading classic books. Thinking about the architecture of contemporary libraries therefore represents for me a web developed in several different directions, among which I do not want, cannot, and will not judge. This will surely be taken up by others more eagerly and much better shortly. My role is different: I would now like to walk with you purposefully and randomly through a few of the many contemporary foreign libraries that I consider inspiring because they successfully capture the nature of the contemporary relationship of readers to books, reading, collecting, and borrowing books architecturally. Along with them, I will also pause at several inspiring projects and design processes of those libraries that were, for various reasons, not constructed or are currently under construction. We will now become, for a moment, not only readers of books but also readers of libraries. With a bit of patience, we may succeed. I would also like to ask in this context, in what sense are the mentioned libraries closed and/or open works of contemporary architecture: What inspires the meeting with readers of both physical and virtual books and how do they themselves become inspiring for these meetings?

1. STOP

classicalizing and simultaneously modernizing: French National Library in Paris (1989–95)

"The library building for the 21st century was a response to certain practical needs. In addition to responding to these needs, we believed it was right for France to clearly signal through an exemplary monument its sense of the value of its intellectual wealth and its confidence in the future of books and reading. (…) I also welcome the work of Dominique Perrault, whose precise arguments have earned my respect. The building he designed is clear and luminous in its symmetry; its lines are restrained; its spaces and functions are conceived simply. (…) Between heaven and earth, the library's esplanade stretches, open to all, as an expansive public space where individuals can meet and mingle among others in a way that is so unique in the public spaces of modern cities." \Francois Mitterrand, 1995

"It is a classical architectural gesture, entirely in the spirit of Paris. Its monumental scale corresponds to the city, and the French seem to have a cool rationality for this kind of project." \Richard Rogers – member of the jury of the international architectural competition, 1994

"To be an architect today means to practice one of the last Renaissance professions that touches all areas of human endeavor. (…) Architecture is not avant-garde art; it is a rearguard art, therefore delaying. It has always been twenty years behind great avant-garde artistic movements, always full of anxiety that it will be contaminated too quickly. Artists have proclaimed the death of art; it is time for architects to manifest the death, decay, disappearance of architecture and replace it with an approach that connects our cities with the world of nature. (…) What fascinates me about the library is the feeling that we have created a mystical place that exceeds all previously known references." \Dominique Perrault – architect of the library, 1995

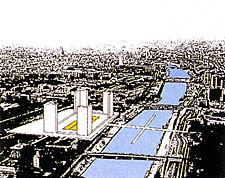

I can perhaps say that the birth of the French National Library was primarily driven by two impulses: the effort to concentrate the French national fund of books published after World War II into one building in the capital and the effort to support the new urban development of the eastern part of Paris. By taking patronage over this project, President Mitterrand clearly indicated that this library is another in the series of prestigious Great Projects (Grands projects), which have been realized in Paris since the second half of the last century under the personal support and oversight of French presidents to this day. The international architectural jury decided that the vision of architect Dominique Perrault best addressed such a task – thus he became the first French architect in a series of international personalities constructing so-called authored architecture in contemporary Paris – that is, architectural works with a distinct authorship.

Architect Perrault developed his design for the new library – a city monument based on the competition program prepared by the working group for the establishment of a public national library, chaired by Serge Goldberg, as well as through his own analysis of the locations of large Parisian parks and public spaces concerning their relationship to the river. Indeed, drawings that capture the Champ de Mars, gardens, and the building of the Invalides, the Tuileries, and the area of the Jardin de Plantes in relation to the Seine clearly validate Perrault's decision to propose a library by the Seine for the eastern part of the city as another of the great Parisian open spaces and at the same time a construction landmark: it became a plateau with an inner atrium defined by four monumental towers at the corners. Perrault's building-park directed the development of public spaces of the city further to the east, across the existing industrial periphery. The initiating potential of this decision is today confirmed not only by the library itself but also by the social and residential blocks newly constructed around it in the thirteenth arrondissement of Paris. The public national library therefore gave the city the expected transformative impulse, while also becoming a separate, standalone structure, as was the case with the buildings of Ancient Greece, classical, and classical architecture.

On one hand, this library, with a total area of 365178m², is meant to represent a public, 'popular' building, partly a supermarket – as the author states (the four towers designed by Perrault are a simple, popular reference as well as a mnemonic aid for even absent-minded readers who understand only figurative signs to discover that the building appearing as four open books facing each other may be a library where more books might be found…). On the other hand, the spiritual ambitions of the library are significant: according to the author, it is also to become partly a temple. And this temple has, in its center, an atrium and in it, rather an artificially planted piece of rainforest than a paradise courtyard. Contrary to the original program, the library maintains not only the national book and audiovisual collection of the second half of but the entire past century. Therefore, the increase in acquisitions, which was intended to occur gradually by adding books to the storage areas along the perimeter of the glass towers, happened all at once prior to the library's opening, and now the glass towers of the library are already practically full – and thus much less translucent than originally intended by the author. The library is divided into four departments: exact sciences and technology; literature and art; economic and political sciences; philosophy, history, and humanities. Around the inner façade with a view into the lower levels of the atrium, there are scientific consultation workplaces (2034 seating places) with books in requested and free selection (500000 volumes), while warehouses and technical operations are on the outer perimeter. In the topmost level, overlooking the upper part of the atrium and the crowns of trees, is the public part of the library with 350000 volumes, 2500 periodical items (and 1556 seating places). This section is accessible to the public from eighteen years old or with a bachelor’s university degree. Between these floors are high-ceilinged mezzanines housing scientific reading rooms, audiovisual and conference halls (with a variable number of seating). In the glass towers, in addition to the automated book transport system, service areas, and storage areas, there is also a variable number of places for the administration and management of the library. The spatial arrangement on various floors is varied and can be repeatedly altered as needed. The number of mezzanines can also vary, along with the usable area of the reading rooms. The building thus does not change its overall volume but can change its total usable area. The interiors of the library, just like the external staircases and the plateau (esplanade) in the exterior, are lined and structured with tropical wood, on which traces of use and patina will be visible. The vertical, rotatable wooden slats that partition and shade the glass façade are also wooden. They allow us to perceive the entire range of building scales from smooth wholes to structured details to fine textures. While all of these specific traces and elements of both the exterior and interior of the building record the passage of time and changes in the flow of spaces of the library, the inner 'forest' – a grove of tall trees in the atrium – according to the author "situates the library into a timelessness whose references are universal"\1 (p. 48). So here the bearer of timelessness and universality of architecture is not the building itself but its connection with the eternally changing nature.

So I can now perhaps also say that the library works with the methods of classical and modern architecture not in a wholly classical or modernizing manner. On the one hand, it acts as an initiating and organizing element for its environment; on the other hand, it employs both architectural and extra-architectural means to express its own openness, multi-component nature, and variability in time and space. It is not only, like Boullée's library design, a utopian building embodying the regular and symmetrical l’image de l’ordre (image of order) in the midst of amorphous and mutable nature. It is also composite architecture, almost manneristically capturing the immaterial transformation of the physical and non-physical where the universal impulse for this change cannot be attributed to a single instance, but to the mutual continuity of hybrid, “artificial-wild" nature with the physical-virtual architecture of the library.

The physical elements that make up the spatial structure of the library are limited to one recurring spatial element – the prism. It is multiplied and arranged together so as to convey a sense of clear, balanced, symmetrical, and stable structuring. This impression, however, is constantly destabilized and re-established in relation to nature as well as to the small traces of changes in the temporal and spatial flows captured by the architecture of the building's exterior and interior. The method of cataloging, storing, and lending books through computer workstations (7 million catalog entries, 13 million entries in the French unified catalog) is understood as a non-physical "element" among physical elements. The interstitial space between the towers-books can then be interpreted by architect Perrault as not only emptiness but also as a virtual volume governed by proportional relationships (Perrault literally speaks of "the proportions of the virtual volume between the towers")\1 (p. 56). Such subordination of virtuality to classic compositional principles leads to the emergence of a classical electronic-physical library. It inspires us to read virtual books in the classic library and to take classic books out into the 'grove' in the atrium, sit beneath a tree, and read. At such a time, the classic library "disappears" while we are reading in it, and in the virtual volume, only our virtual self reads.

We can also let the library re-emerge before our eyes and take a closer look, read its signs and symbols. And we need not first become monks, university students and professors, scholars, shoppers in a supermarket, or other "initiated" ones than the initiates of "writing libraries". The publicly accessible, symbolic place that the architect created together with artists Richard Serra and James Turrell provides us with several possible layers and scales for reading:

a \ Scale of the city: the building can be an open urban gate facing north, south, east, and west.

b \ Scale of a building in general: the building can be a fortress with four towers and an inner courtyard overgrown with trees. A monastic building. It is also a silo for books, a vertical glass labyrinth, a minimalist installation of prisms, land art. An unfinished frame whose top and center is virtual... etc.

c \ Scale of the library: the four towers – books stretch an open space for reading both books and the library itself. Glass books filling up with books. Completing the library is a flow, an accumulation, a storage of knowledge, a slow and apparent cultural sedimentation.

d \ Scale of spatial puzzles and paradoxes: can one read in Paris and at the same time outside Paris? Are there open books in open books, and in them again...? How to read spaces transparent-opaque? Is the inversion of the book also a kind of book? Is the classic pedestal and frame... etc.

|

| Competition project of BNF in Paris by Dominique Perrault (1989) |

"It is a classical architectural gesture, entirely in the spirit of Paris. Its monumental scale corresponds to the city, and the French seem to have a cool rationality for this kind of project." \Richard Rogers – member of the jury of the international architectural competition, 1994

"To be an architect today means to practice one of the last Renaissance professions that touches all areas of human endeavor. (…) Architecture is not avant-garde art; it is a rearguard art, therefore delaying. It has always been twenty years behind great avant-garde artistic movements, always full of anxiety that it will be contaminated too quickly. Artists have proclaimed the death of art; it is time for architects to manifest the death, decay, disappearance of architecture and replace it with an approach that connects our cities with the world of nature. (…) What fascinates me about the library is the feeling that we have created a mystical place that exceeds all previously known references." \Dominique Perrault – architect of the library, 1995

|

| Competition project of BNF in Paris by Dominique Perrault (1989) |

Architect Perrault developed his design for the new library – a city monument based on the competition program prepared by the working group for the establishment of a public national library, chaired by Serge Goldberg, as well as through his own analysis of the locations of large Parisian parks and public spaces concerning their relationship to the river. Indeed, drawings that capture the Champ de Mars, gardens, and the building of the Invalides, the Tuileries, and the area of the Jardin de Plantes in relation to the Seine clearly validate Perrault's decision to propose a library by the Seine for the eastern part of the city as another of the great Parisian open spaces and at the same time a construction landmark: it became a plateau with an inner atrium defined by four monumental towers at the corners. Perrault's building-park directed the development of public spaces of the city further to the east, across the existing industrial periphery. The initiating potential of this decision is today confirmed not only by the library itself but also by the social and residential blocks newly constructed around it in the thirteenth arrondissement of Paris. The public national library therefore gave the city the expected transformative impulse, while also becoming a separate, standalone structure, as was the case with the buildings of Ancient Greece, classical, and classical architecture.

|

| Competition project of BNF in Paris by Dominique Perrault (1989) |

So I can now perhaps also say that the library works with the methods of classical and modern architecture not in a wholly classical or modernizing manner. On the one hand, it acts as an initiating and organizing element for its environment; on the other hand, it employs both architectural and extra-architectural means to express its own openness, multi-component nature, and variability in time and space. It is not only, like Boullée's library design, a utopian building embodying the regular and symmetrical l’image de l’ordre (image of order) in the midst of amorphous and mutable nature. It is also composite architecture, almost manneristically capturing the immaterial transformation of the physical and non-physical where the universal impulse for this change cannot be attributed to a single instance, but to the mutual continuity of hybrid, “artificial-wild" nature with the physical-virtual architecture of the library.

|

| French National Library in Paris by D.Perrault (1995) |

We can also let the library re-emerge before our eyes and take a closer look, read its signs and symbols. And we need not first become monks, university students and professors, scholars, shoppers in a supermarket, or other "initiated" ones than the initiates of "writing libraries". The publicly accessible, symbolic place that the architect created together with artists Richard Serra and James Turrell provides us with several possible layers and scales for reading:

a \ Scale of the city: the building can be an open urban gate facing north, south, east, and west.

b \ Scale of a building in general: the building can be a fortress with four towers and an inner courtyard overgrown with trees. A monastic building. It is also a silo for books, a vertical glass labyrinth, a minimalist installation of prisms, land art. An unfinished frame whose top and center is virtual... etc.

c \ Scale of the library: the four towers – books stretch an open space for reading both books and the library itself. Glass books filling up with books. Completing the library is a flow, an accumulation, a storage of knowledge, a slow and apparent cultural sedimentation.

d \ Scale of spatial puzzles and paradoxes: can one read in Paris and at the same time outside Paris? Are there open books in open books, and in them again...? How to read spaces transparent-opaque? Is the inversion of the book also a kind of book? Is the classic pedestal and frame... etc.

2. STOP

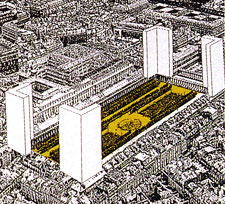

decomposing and simultaneously recomposing: this stop contains two: the first is longer, the second is quite short. The first (A) is the unrealized project of the currently presented French National Library, authored by Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas (office OMA), and the second stop (B) is the project of the just-constructed library in Seattle by the same author.

A

"At a moment when the electronic revolution seemingly dissolves everything solid – ridding itself of all need for concentration and embodiment – the ultimate idea of a library appears entirely absurd." \Rem Koolhaas, 1998

"Everyone is working on a utopia of fully integrated information systems that will materialize even before the opening of the [French National Library (FNK), note by the author]: books, films, music recordings, computers will be read from a single 'miraculous' board or table. The future does not promise the end of the book but an age of new equalities." \Rem Koolhaas, 1998

"When we finally stopped thinking about dimensions, it is stated that [the library, note by the author] will have 3-5 times more visitors than [the gallery, note by the author].

Beaubourg. A communist project in a post-ideological age?" \Rem Koolhaas, 1998

According to architect Rem Koolhaas, the French National Library, with an emphasis on the book and multimedia records created during the 20th century, stands a much larger chance of becoming a conglomerate of a giant cinema, media library, and library than a classical or modern (universally multifunctional) library. Similarly to Perrault, Koolhaas also designs the new library building as a vast stage, into which however only the storage of books, transport systems, and horizontal communications are placed. Above this platform, he then places another compact block of individual specialized divisions of the library. Not only Perrault but also Koolhaas metaphorically interprets the space defined by his building.

He does not consider it emptiness, but rather: "the absence of a building – a gap cut in a solid block of information"\2 (p. 616). Koolhaas's arrangement of the library's functions and forms brings us closer to a self-ironic entry from the author's diary, which is not entirely free of subtle absurdity:

"May 12

›Scientific‹ day.

Take:

1 board of storage

1 board of administration/offices

1 board of horizontal communication areas/elevators

Laminate them together to form a single large building.

Pull up the wires of the rolled-up reading rooms as if it were a demolished Tower of Babel overlooking the Seine. Now cut the boards horizontally: each cut corresponds to the program (operation, function) of the building. You cannot go wrong. Floor plan = cut."\2 (p. 622)

Reading rooms are supposed to spirally wind around this block of densely arranged "boards" and provide readers with views of the city and the river. In the second phase of the project, the reading rooms are, on the contrary, "cut out" from the block of boards like cavities. The author says: "...they are not designed, they are simply cut out. Can this formulation free us from the burdensome pretense of discoveries?"\2 (p. 626)

Thanks to this "carpentry and stonemasonry" method of removing mass from a solid block, the building attains its resultant porous and "holey" shape, through which nine regularly distributed elevator shafts and several spacious, irregular social spaces – cavities – run. Here, removal ends and the addition of mass comes back to the forefront. Koolhaas contemplates "formless architecture" \2 (p. 638), which, in relation to this place in the city, would create a library while not forming either a classical or modern form, respectively, a pre-form (archetype, ideal shape, unified work). Individual libraries and reading rooms are then not proposed by Koolhaas, as by Perrault, in the spirit of a continuous, homogeneous interior structured empty container, but as separate, distinct, and separated spaces of unique natures, functions, and forms. Thus, as a vast singular, related, and simultaneously mutually differentiated bodies (monads, planets, cells, etc.), which are independently secured to the supporting structure of the building outside of themselves and the exterior envelope of the library. A similar arrangement of reading rooms and study areas detaching from an otherwise relatively homogeneous interior space of the building was recently chosen in the design of a library in Peckham, London (?–1999) by architect William Alsop.

In Koolhaas's office, an inverse model of this library is built: what is to be full in reality is empty in the model and vice versa. A joint discussion and opposition is underway. Work continues. The last one to be created is a glass façade, and then only the final presentation of the project. Four years later, Koolhaas recaps the joint discussion (which also included silence) of architects, builders, artists, and theorists: "Other disciplines enjoyed their newly gained freedom: hybridity, locality, informality, chance, singularity, irregularity, exceptionality – while architecture was stuck in consistency, repetition, regularity, grids, generality, comprehensiveness, formality, and prejudice. Our work became a joint challenge for architectural and engineering exploration of the aforementioned freedoms. It became a reclaiming of the cut. By expressing our shared dissatisfaction with the operation formulated only based on unraveling the skeins of our burgeoning subconscious. It also became the cancellation of a single, grandiose solution integrating structure and operation. It was also, frankly, an exploration of a building that will not only be different, but will also look different: due to its authentic novelty." \2 (p. 667–8)

It is clear that in the design of the twenty-storey library, the individual operations were positioned partially with respect to the competition program (function) and partially randomly. All floors of the building are traversed by warehouses and offices. From them, audiovisual and screening halls were carved out on the fourth subterranean level, as well as large cabins for watching videos, television programs, and listening to music recordings. Above them are the music, video, and film libraries, along with conference halls (3rd floor). The music library and the moving image library have their space not only one floor higher (2nd floor) but also in the exhibition halls and galleries of the following floor (1st floor). At ground level, the upper and lower floors of the library are accessed by elevators and escalators from an open, nine meters high space without walls. The ceiling and floor of this entrance plateau is designed from frosted, milky glass, through which light from the interior of the library can penetrate. Here, large electronic boards – screens are to be installed to provide visitors with information about events taking place in the library.

For visitors who would like to exit the building while not completely leaving the library, an internal atrium has not been proposed, but a restaurant, gym, swimming pool, and park with a view on the library roof. Between the first and last floors, there are then eighteen floors of mentioned continuous warehouses – places perforated only by conference rooms and reading rooms with ovoid and orthogonal forms. Unlike Perrault, however, Koolhaas does not consider any of the spaces of his architecture as any kind of universal virtual volume. He views them as the absence of a house. As a virtual house. We are invited to attempt to perceive the virtuality in the context of the architecture in which we live and thus enrich our existing, both spiritual and bodily experience of living. We can linger in virtuality and somehow perhaps dwell there – but above all, we occupy our actual homes and houses more comprehensively and simultaneously more differentiated thanks to it. Koolhaas’s project is not – like Perrault's project – inspired by the thoughts of the classics and utopists. It considers contemporary notions and opinions on place (topos), the non-existence of place (atopia), and re-evaluation: decomposing and recomposing places (distopia).

If distopia is a mirror in which place is multiplied and laterally reversed, if distopia is simultaneously a ship that sails from place to place and is itself also some kind of "place" of its own, then Koolhaas's spaces-cavities and spaces-ovoids levitating in the warehouses of books and simultaneously in the places multiplied by the "miraculous" boards and tables that transport us between sound, image, and text places represent a hybrid, "distopian topos" of contemporary architecture. In this sense, Koolhaas's library allows itself to be inspired by our experience and knowledge of virtuality much more openly than Perrault's library. And how does Koolhaas's library inspire our meeting with the book? Just as we ourselves take the book from the shelves and hold it in our hands, the library extracts the readers from the orthogonal order of its warehouses and offices and settles them in reading within expansive spaces, some of which are shaped like a winding Möbius strip: "Imagine a room where the wall flows smoothly into the ceiling, which again flows into the wall, and that into the floor... The room winds into a loop. ('Room loops the loop.')\2 (p. 634)

This Koolhaas library project was not built, but its idea of social and simultaneously individualized spaces removed from the rectangular grid of logistics-managed warehouses and offices is today followed, developed, and cited by many contemporary architects. Sometimes the development of architecture is important not only for projects that have been built, with which we have our own, experienced and conceptual experience, but also for "ideal" projects, known as ideas recorded in images, models, and texts that inspire our further understanding and creation of architecture. They may not have been realized partly because they did not find a similarly attuned client and investor: they did not meet the jury's standards, did not appeal to citizens and state administration, and politicians did not see their intentions reflected in them. Sometimes it suffices for these inspiring works to "only" find a more open-minded client, another country, and a suitable time for construction realization. Just like Koolhaas's library proposal in downtown Seattle, USA.

B

The eleven-storey building of the public library in Seattle with 1,400,000 volumes of books, printed materials, and audiovisual records represents another version of Koolhaas's previous proposal and his other two unrealized library projects for the Jussieu University in Paris (1999). Koolhaas's view on libraries does not radically change:

"The library transforms from a space for reading into a social center with multiple competencies." This library is a combination of five platforms and five programmatic or functional clusters – among which there are also administrative and organizational platforms – spaces for the work of librarians, their interaction and "play" with media. The fact that the content of the library can be recorded on a chip, and also the fact that the library can store the contents of all other libraries in the country, leads, according to Koolhaas, to several prevailing characteristics of the library in Seattle:

\ it is compressed, condensed, and re-evaluates the methods of storing book collections and digital data;

\ it is flexible in that each of its parts has its own, specific flexibility;

\ it is possible to distinguish several form layers (platforms, plateaus) and programmatic (functional) clusters that may or may not be interconnected. One of the platforms is also a virtual platform;

\ the diagram of organizing the virtual space of the library becomes the starting point for composing the physical building, which is realized by the readers and visitors of the library through their presence and activities at a specific place and time.

A

|

| Competition project OMA on Très Grande Bibliothèque (1989), photo: Hans Welrlemann |

"Everyone is working on a utopia of fully integrated information systems that will materialize even before the opening of the [French National Library (FNK), note by the author]: books, films, music recordings, computers will be read from a single 'miraculous' board or table. The future does not promise the end of the book but an age of new equalities." \Rem Koolhaas, 1998

"When we finally stopped thinking about dimensions, it is stated that [the library, note by the author] will have 3-5 times more visitors than [the gallery, note by the author].

Beaubourg. A communist project in a post-ideological age?" \Rem Koolhaas, 1998

According to architect Rem Koolhaas, the French National Library, with an emphasis on the book and multimedia records created during the 20th century, stands a much larger chance of becoming a conglomerate of a giant cinema, media library, and library than a classical or modern (universally multifunctional) library. Similarly to Perrault, Koolhaas also designs the new library building as a vast stage, into which however only the storage of books, transport systems, and horizontal communications are placed. Above this platform, he then places another compact block of individual specialized divisions of the library. Not only Perrault but also Koolhaas metaphorically interprets the space defined by his building.

He does not consider it emptiness, but rather: "the absence of a building – a gap cut in a solid block of information"\2 (p. 616). Koolhaas's arrangement of the library's functions and forms brings us closer to a self-ironic entry from the author's diary, which is not entirely free of subtle absurdity:

"May 12

›Scientific‹ day.

Take:

1 board of storage

1 board of administration/offices

1 board of horizontal communication areas/elevators

Laminate them together to form a single large building.

Pull up the wires of the rolled-up reading rooms as if it were a demolished Tower of Babel overlooking the Seine. Now cut the boards horizontally: each cut corresponds to the program (operation, function) of the building. You cannot go wrong. Floor plan = cut."\2 (p. 622)

|

| Competition project OMA on Très Grande Bibliothèque (1989), photo: Hans Welrlemann |

Thanks to this "carpentry and stonemasonry" method of removing mass from a solid block, the building attains its resultant porous and "holey" shape, through which nine regularly distributed elevator shafts and several spacious, irregular social spaces – cavities – run. Here, removal ends and the addition of mass comes back to the forefront. Koolhaas contemplates "formless architecture" \2 (p. 638), which, in relation to this place in the city, would create a library while not forming either a classical or modern form, respectively, a pre-form (archetype, ideal shape, unified work). Individual libraries and reading rooms are then not proposed by Koolhaas, as by Perrault, in the spirit of a continuous, homogeneous interior structured empty container, but as separate, distinct, and separated spaces of unique natures, functions, and forms. Thus, as a vast singular, related, and simultaneously mutually differentiated bodies (monads, planets, cells, etc.), which are independently secured to the supporting structure of the building outside of themselves and the exterior envelope of the library. A similar arrangement of reading rooms and study areas detaching from an otherwise relatively homogeneous interior space of the building was recently chosen in the design of a library in Peckham, London (?–1999) by architect William Alsop.

In Koolhaas's office, an inverse model of this library is built: what is to be full in reality is empty in the model and vice versa. A joint discussion and opposition is underway. Work continues. The last one to be created is a glass façade, and then only the final presentation of the project. Four years later, Koolhaas recaps the joint discussion (which also included silence) of architects, builders, artists, and theorists: "Other disciplines enjoyed their newly gained freedom: hybridity, locality, informality, chance, singularity, irregularity, exceptionality – while architecture was stuck in consistency, repetition, regularity, grids, generality, comprehensiveness, formality, and prejudice. Our work became a joint challenge for architectural and engineering exploration of the aforementioned freedoms. It became a reclaiming of the cut. By expressing our shared dissatisfaction with the operation formulated only based on unraveling the skeins of our burgeoning subconscious. It also became the cancellation of a single, grandiose solution integrating structure and operation. It was also, frankly, an exploration of a building that will not only be different, but will also look different: due to its authentic novelty." \2 (p. 667–8)

It is clear that in the design of the twenty-storey library, the individual operations were positioned partially with respect to the competition program (function) and partially randomly. All floors of the building are traversed by warehouses and offices. From them, audiovisual and screening halls were carved out on the fourth subterranean level, as well as large cabins for watching videos, television programs, and listening to music recordings. Above them are the music, video, and film libraries, along with conference halls (3rd floor). The music library and the moving image library have their space not only one floor higher (2nd floor) but also in the exhibition halls and galleries of the following floor (1st floor). At ground level, the upper and lower floors of the library are accessed by elevators and escalators from an open, nine meters high space without walls. The ceiling and floor of this entrance plateau is designed from frosted, milky glass, through which light from the interior of the library can penetrate. Here, large electronic boards – screens are to be installed to provide visitors with information about events taking place in the library.

|

| Competition project OMA on Très Grande Bibliothèque (1989), photo: Hans Welrlemann |

If distopia is a mirror in which place is multiplied and laterally reversed, if distopia is simultaneously a ship that sails from place to place and is itself also some kind of "place" of its own, then Koolhaas's spaces-cavities and spaces-ovoids levitating in the warehouses of books and simultaneously in the places multiplied by the "miraculous" boards and tables that transport us between sound, image, and text places represent a hybrid, "distopian topos" of contemporary architecture. In this sense, Koolhaas's library allows itself to be inspired by our experience and knowledge of virtuality much more openly than Perrault's library. And how does Koolhaas's library inspire our meeting with the book? Just as we ourselves take the book from the shelves and hold it in our hands, the library extracts the readers from the orthogonal order of its warehouses and offices and settles them in reading within expansive spaces, some of which are shaped like a winding Möbius strip: "Imagine a room where the wall flows smoothly into the ceiling, which again flows into the wall, and that into the floor... The room winds into a loop. ('Room loops the loop.')\2 (p. 634)

This Koolhaas library project was not built, but its idea of social and simultaneously individualized spaces removed from the rectangular grid of logistics-managed warehouses and offices is today followed, developed, and cited by many contemporary architects. Sometimes the development of architecture is important not only for projects that have been built, with which we have our own, experienced and conceptual experience, but also for "ideal" projects, known as ideas recorded in images, models, and texts that inspire our further understanding and creation of architecture. They may not have been realized partly because they did not find a similarly attuned client and investor: they did not meet the jury's standards, did not appeal to citizens and state administration, and politicians did not see their intentions reflected in them. Sometimes it suffices for these inspiring works to "only" find a more open-minded client, another country, and a suitable time for construction realization. Just like Koolhaas's library proposal in downtown Seattle, USA.

B

|

| Seattle Public Library by OMA/LMN (2004) |

"The library transforms from a space for reading into a social center with multiple competencies." This library is a combination of five platforms and five programmatic or functional clusters – among which there are also administrative and organizational platforms – spaces for the work of librarians, their interaction and "play" with media. The fact that the content of the library can be recorded on a chip, and also the fact that the library can store the contents of all other libraries in the country, leads, according to Koolhaas, to several prevailing characteristics of the library in Seattle:

\ it is compressed, condensed, and re-evaluates the methods of storing book collections and digital data;

\ it is flexible in that each of its parts has its own, specific flexibility;

\ it is possible to distinguish several form layers (platforms, plateaus) and programmatic (functional) clusters that may or may not be interconnected. One of the platforms is also a virtual platform;

\ the diagram of organizing the virtual space of the library becomes the starting point for composing the physical building, which is realized by the readers and visitors of the library through their presence and activities at a specific place and time.

3. STOP – multiply hybrid:

Here I could mention many libraries, from those historicizing and eclectic to those for which I do not have a more precise model, direction, school, or other compartment defined. Frankly, I am not tempted to engage with the historicizing and eclectic libraries, which are much more knowledgeable dealt with by other historians and theorists of architecture. I will briefly mention three libraries here, for which I find it difficult to find any definitions, but which are somehow, although it is not always clear how, important. Often their poetics, relationship to other works, sensitivity to contemporary developments is what speaks to me about them.

A

The first is the Central Scientific Library of the Technical University in Delft (project 1993–95, realization 1996–98)

"Of course, we discuss modern electronic media and also the question of whether books and libraries have a future. After all, all information will probably be accessible anytime and from anywhere: from the smallest study room to the largest computer laboratory. But the university library also offers space for cultivating our knowledge and for research, for concentration and reflection. It is also a space intended for meetings, in which we can share stimulating ideas together." \Francine Houben, 1998

"I dream of a building full of books, more books, and again books – with beautiful circular reading rooms. A building where we can see the books, touch them, and smell them. The abyss between the dream and reality is, however, enormous. The operation of the library presupposes that the books will be in storage." \Francine Houben, 1998

"I would like to bring a little romance into the Technical University campus." \Francine Houben, 1998

The library in Delft was the third library that the architects of the Dutch studio Mecanoo worked on. After the faculty and public library, it was the first university library – more precisely, the central research university library, whose role is to serve not only the students and teachers of the university in Delft but also to take care of the central catalog of scientific and research literature of all Dutch universities. Director Leo Waaijers emphasized in the program of the future library, managing around one million volumes, the establishment of a central registry and regulation of the flow of information through computer means. He compared his vision of the library to an airport terminal.

Architect Francine Houben, who led the project of this library at Mecanoo, designed the library as a layer of landscape relief. The grass-covered roof of the library touches the ground on one side and rises like a rising terrain wave on the other: "The library is a building that does not want to be a building but a landscape. (…) It should remain a landscape, with softly curved shapes and sharply cut edges. People should be able to literally walk through the library as in the landscape."\3 This conception of the library realized as an artificial embankment has evident ecological, urban, and architectural motivations. The grassy roof of the library has an accumulation potential, protecting the library building from abrupt changes in outside temperature. Cool air is sucked into the building at night, stored underground, and during the day is then used to cool the library's interiors, including the computer laboratory. The building with a grassy roof also brings a substantial area of maintained public greenery and mature trees to the university. From an urban planning perspective, it forms a forecourt, an entrance area into the adjacent university hall building.

With some exaggeration, it can be said that this library-land wave is functional in three scales (contexts) and in two ways simultaneously: from the inside and from the outside. As a house and as a meadow.

Ultimately, architect Francine Houben partly succeeded in realizing her dream of a library full of books, books, and more books: we enter the library building through a glass façade, behind which we can see directly into the interior of the book stacks partitioned by glass partitions. Even though we cannot touch the books or smell them (as we can the grass on the roof), we can at least catch a glimpse of them before we sit at computers to find them again and track their journey to us and our journey to them. In addition to books in free selection, stored on wooden shelves, we therefore also have an overview of the movement of other books throughout the building (including their transportation via the glass conveyor of books). The department of rare books and prints was to be placed behind purple glass according to the project. In the final solution, the glass is white, but the interior partitions (blue) and the wings of the doors to individual sections of the library are colored (red). The room for 300 computer workstations is partitioned into small work boxes so that readers have privacy and the bluish glow of the monitors is somewhat isolated. The main spaces of the library – reading rooms – are separately located in a cone-tower that illuminates the library’s interior with natural light: "The large form should contrast with the landscape. We thought long about its exact shape. It should be circular, but we had doubts about how to finish it. Ultimately, the logic of construction determined its shape: a cone – like an Indian teepee in the landscape. The beauty of the cone lies in the fact that it is a pure, constructive form – a symbol of the Technical University. The cone provides space for internal, enclosed reading rooms. They are suspended at the top of the cone – thus we gain beautifully expansive spaces without columns. The cone as a symbol of technology, but also of calmness and contemplation. The cone, like a pushpin, connects architectural form with 'the endless, vast landscape'." \3 Unlike Perrault's project, where nature is at the center of the library, here there is no center – only an implicitly decentralized perimeter, in which there is space for the ideal body. In addition to the aforementioned program, the neighboring hall designed by the Dutch studio Van den Broek and Bakema also influenced the formation of the library.

Building another house next to such a prominent building is a fundamental decision. Francine Houben considers the hall building a "concrete sculpture". The design of the library-land respects and supports the neighboring hall rather than detracting from its monumentality: "As a result, there are actually two new buildings: the library supports the landscape, and the hall settles into the landscape."\3 It is a remarkable example of participation with the environment and thus a construction that continues to connect the chain where others create monads. Architect Francine Houben also rejected the university's offer to design the extension of this hall. On the contrary, she proposed to the university that the budget for the extension be used for the renovation of the inner spaces and reconstruction of the building, thereby increasing the number of places in the dining hall to the number required by the university, and the hall building did not need to be extended. But how to evaluate the thoughtfulness of what was not built?

In comparison with Perrault's and Koolhaas's designs, this small library presents a completely different way of cooperation of architecture with the surrounding environment. The building is not only contextual; it is also "collaborative". Glass is not only used on the surface (to see inside the library and outside from it) but also in the interiors (so that the building can be seen almost "through and through"). Passersby, readers, and staff then see not only the books on the shelves but also, as is more common in Dutch architecture, have an overview of the administrative and management mechanisms of the library’s operation as a public institution. The library is therefore not only user-friendly but also operationally more transparent and less separated from the public space than in the previous library projects and other buildings of the university. If we want, we can consider this a visual connection between the outer public space and the spaces of public institutions. This solution coincides with Koolhaas's project in the intuition that reading a book in the contemporary library will rather take place in a separated, non-right-angled space. In accordance with the previous two projects, this library also arrives at a technologically well-equipped compact geometric form (prism, cube, cone). However, Francine Houben most distinctly, albeit additively, attaches a form governed rather topologically than geometrically to the fundamental body. For all the projects presented thus far, special rooms are reserved for computer technologies here. The overall order and operation of the building (except for Koolhaas) approaches telematic experiences with electronic media rather reservedly than allowing itself to be truly creatively inspired by them.

B

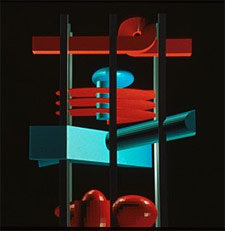

The second stop is the sketches for the unrealized project of the European Cultural and Information Library (BEIC) in Milan (2001) by architect Jo Coenen, analyzing the elements and flows of an information library.

C

The final stop is, in my opinion, the most open contribution to libraries in the information age: Mediatheque in the Japanese city of Sendai (project 1995–1997, realization 1998–2000).

" Designboom: Which of your projects has brought you the greatest satisfaction?"

Toyo Ito: Mediatheque in Sendai. I worked on it for six years, and it was enriching."

\From the interview with architect Toyo Ito for the online magazine Designboom, 2001

"The era when museums, libraries, and theaters proudly showcased their archetypal presence is over. The existence of images on walls and books on paper is no longer absolute. Electronic media relativize it." \Toyo Ito, 1997

"The mediatheque will be an archetype of entirely new architecture. It will be inhabited by the dual corporeality of contemporary people – their corporeality formed by the flow of electrons and also their corporeality simple, corresponding to nature." \Toyo Ito, 1997

The words of architect Toyo Ito have been cited many times, according to which the mediatheque in Sendai is inspired by blades of water grass dancing in the flow of water. That is, let’s say, a more familiar and popular metaphor of the author. Less cited in this context are statements addressing other areas of our imagination: "Since ancient times, the human body has been linked to nature through organs in which water and air circulate. Today, people are equipped with an electronic body, in which information circulates – thus they connect with the world of information through the networks of this second body. (…) The greatest challenge for us today is the question of how to connect these two types of corporeality." \4 Similar questions Toyo Ito poses to architecture: "Through contemporary architecture, we must establish a relationship with the electronic environment by incorporating information flows and turbulence into it. The question is how we can connect simple space related to nature and virtual space, which is related to the world through electronic networks. A space that could integrate both is perhaps conceivable as electronic-biomorphic." \4

In the concept of the library, this idea is concretized through the work with three elements:

\ planes (6 horizontal communication planes);

\ tubes (13 vertical load-bearing and communication flows);

\ skin (double-glazed façade).

The role of the structure combining these three elements is to create a space for connecting the library (150,000 volumes), center of visual media, theater, gallery, computer workstations with printing workshops and copying centers, in which visitors can self-"publish" a book and/or create various visual, audio, and data records. The routes and procedures for publicly preserving and exchanging information are interlinked non-homogeneously here. The mediatheque is so far the only building of this kind. It represents a forming approach to redefining the place of the library in contemporary culture.

Notes and literature

\1 Bibliothèque nationale de France 1989 – 1995. Dominique Perrault architecte. (Ed.) Jacques, M., Lauriot-dit-Prévost, G., Artemis, Paris 1995.

\2 S,M,L,XL. (Ed.) O.M.A., Koolhaas, R., Mau, B., The Monacelli Press, New York 1995.

\3 Houben, Francine: "Library of the Future", lecture given at the conference Space of the Future – Libraries of the 21st Century, Helsinki, Finland, June 2 – 3, 2002 (http://www.lib.hel.fi/conf02/).

\4 Ito, Toyo: Image of Architecture in Electronic Age, (http://www.um.u-tokyo.ac.jp/publish_db/1997VA/english/virtual/01.html).

A

|

| Central Scientific Library of TU Delft by Mecanoo (1998) |

"Of course, we discuss modern electronic media and also the question of whether books and libraries have a future. After all, all information will probably be accessible anytime and from anywhere: from the smallest study room to the largest computer laboratory. But the university library also offers space for cultivating our knowledge and for research, for concentration and reflection. It is also a space intended for meetings, in which we can share stimulating ideas together." \Francine Houben, 1998

"I dream of a building full of books, more books, and again books – with beautiful circular reading rooms. A building where we can see the books, touch them, and smell them. The abyss between the dream and reality is, however, enormous. The operation of the library presupposes that the books will be in storage." \Francine Houben, 1998

"I would like to bring a little romance into the Technical University campus." \Francine Houben, 1998

The library in Delft was the third library that the architects of the Dutch studio Mecanoo worked on. After the faculty and public library, it was the first university library – more precisely, the central research university library, whose role is to serve not only the students and teachers of the university in Delft but also to take care of the central catalog of scientific and research literature of all Dutch universities. Director Leo Waaijers emphasized in the program of the future library, managing around one million volumes, the establishment of a central registry and regulation of the flow of information through computer means. He compared his vision of the library to an airport terminal.

Architect Francine Houben, who led the project of this library at Mecanoo, designed the library as a layer of landscape relief. The grass-covered roof of the library touches the ground on one side and rises like a rising terrain wave on the other: "The library is a building that does not want to be a building but a landscape. (…) It should remain a landscape, with softly curved shapes and sharply cut edges. People should be able to literally walk through the library as in the landscape."\3 This conception of the library realized as an artificial embankment has evident ecological, urban, and architectural motivations. The grassy roof of the library has an accumulation potential, protecting the library building from abrupt changes in outside temperature. Cool air is sucked into the building at night, stored underground, and during the day is then used to cool the library's interiors, including the computer laboratory. The building with a grassy roof also brings a substantial area of maintained public greenery and mature trees to the university. From an urban planning perspective, it forms a forecourt, an entrance area into the adjacent university hall building.

With some exaggeration, it can be said that this library-land wave is functional in three scales (contexts) and in two ways simultaneously: from the inside and from the outside. As a house and as a meadow.

Ultimately, architect Francine Houben partly succeeded in realizing her dream of a library full of books, books, and more books: we enter the library building through a glass façade, behind which we can see directly into the interior of the book stacks partitioned by glass partitions. Even though we cannot touch the books or smell them (as we can the grass on the roof), we can at least catch a glimpse of them before we sit at computers to find them again and track their journey to us and our journey to them. In addition to books in free selection, stored on wooden shelves, we therefore also have an overview of the movement of other books throughout the building (including their transportation via the glass conveyor of books). The department of rare books and prints was to be placed behind purple glass according to the project. In the final solution, the glass is white, but the interior partitions (blue) and the wings of the doors to individual sections of the library are colored (red). The room for 300 computer workstations is partitioned into small work boxes so that readers have privacy and the bluish glow of the monitors is somewhat isolated. The main spaces of the library – reading rooms – are separately located in a cone-tower that illuminates the library’s interior with natural light: "The large form should contrast with the landscape. We thought long about its exact shape. It should be circular, but we had doubts about how to finish it. Ultimately, the logic of construction determined its shape: a cone – like an Indian teepee in the landscape. The beauty of the cone lies in the fact that it is a pure, constructive form – a symbol of the Technical University. The cone provides space for internal, enclosed reading rooms. They are suspended at the top of the cone – thus we gain beautifully expansive spaces without columns. The cone as a symbol of technology, but also of calmness and contemplation. The cone, like a pushpin, connects architectural form with 'the endless, vast landscape'." \3 Unlike Perrault's project, where nature is at the center of the library, here there is no center – only an implicitly decentralized perimeter, in which there is space for the ideal body. In addition to the aforementioned program, the neighboring hall designed by the Dutch studio Van den Broek and Bakema also influenced the formation of the library.

|

| Central Scientific Library of TU Delft by Mecanoo (1998) |

In comparison with Perrault's and Koolhaas's designs, this small library presents a completely different way of cooperation of architecture with the surrounding environment. The building is not only contextual; it is also "collaborative". Glass is not only used on the surface (to see inside the library and outside from it) but also in the interiors (so that the building can be seen almost "through and through"). Passersby, readers, and staff then see not only the books on the shelves but also, as is more common in Dutch architecture, have an overview of the administrative and management mechanisms of the library’s operation as a public institution. The library is therefore not only user-friendly but also operationally more transparent and less separated from the public space than in the previous library projects and other buildings of the university. If we want, we can consider this a visual connection between the outer public space and the spaces of public institutions. This solution coincides with Koolhaas's project in the intuition that reading a book in the contemporary library will rather take place in a separated, non-right-angled space. In accordance with the previous two projects, this library also arrives at a technologically well-equipped compact geometric form (prism, cube, cone). However, Francine Houben most distinctly, albeit additively, attaches a form governed rather topologically than geometrically to the fundamental body. For all the projects presented thus far, special rooms are reserved for computer technologies here. The overall order and operation of the building (except for Koolhaas) approaches telematic experiences with electronic media rather reservedly than allowing itself to be truly creatively inspired by them.

B

The second stop is the sketches for the unrealized project of the European Cultural and Information Library (BEIC) in Milan (2001) by architect Jo Coenen, analyzing the elements and flows of an information library.

C

The final stop is, in my opinion, the most open contribution to libraries in the information age: Mediatheque in the Japanese city of Sendai (project 1995–1997, realization 1998–2000).

" Designboom: Which of your projects has brought you the greatest satisfaction?"

Toyo Ito: Mediatheque in Sendai. I worked on it for six years, and it was enriching."

\From the interview with architect Toyo Ito for the online magazine Designboom, 2001

"The era when museums, libraries, and theaters proudly showcased their archetypal presence is over. The existence of images on walls and books on paper is no longer absolute. Electronic media relativize it." \Toyo Ito, 1997

"The mediatheque will be an archetype of entirely new architecture. It will be inhabited by the dual corporeality of contemporary people – their corporeality formed by the flow of electrons and also their corporeality simple, corresponding to nature." \Toyo Ito, 1997

|

| Model of Mediatheque in Sendai from 1995 dedicated to MoMA. |

In the concept of the library, this idea is concretized through the work with three elements:

\ planes (6 horizontal communication planes);

\ tubes (13 vertical load-bearing and communication flows);

\ skin (double-glazed façade).

The role of the structure combining these three elements is to create a space for connecting the library (150,000 volumes), center of visual media, theater, gallery, computer workstations with printing workshops and copying centers, in which visitors can self-"publish" a book and/or create various visual, audio, and data records. The routes and procedures for publicly preserving and exchanging information are interlinked non-homogeneously here. The mediatheque is so far the only building of this kind. It represents a forming approach to redefining the place of the library in contemporary culture.

Notes and literature

\1 Bibliothèque nationale de France 1989 – 1995. Dominique Perrault architecte. (Ed.) Jacques, M., Lauriot-dit-Prévost, G., Artemis, Paris 1995.

\2 S,M,L,XL. (Ed.) O.M.A., Koolhaas, R., Mau, B., The Monacelli Press, New York 1995.

\3 Houben, Francine: "Library of the Future", lecture given at the conference Space of the Future – Libraries of the 21st Century, Helsinki, Finland, June 2 – 3, 2002 (http://www.lib.hel.fi/conf02/).

\4 Ito, Toyo: Image of Architecture in Electronic Age, (http://www.um.u-tokyo.ac.jp/publish_db/1997VA/english/virtual/01.html).

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment