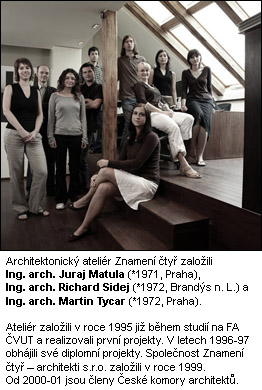

<SIGN_OF_FOUR>

interview with Richard Sidey and Juraj Matula

|

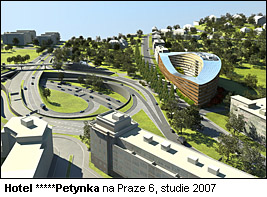

After ten years, the phrase The Sign of Four in the Czech environment associates more with a successful architectural practice than Doyle's book. The office is located in the very center of Prague, near Senovážné náměstí. We interrupted Richard Sidej and Juraj Matula in their work here. The third partner, Martin Tycar, continued working on the current project of a five-star hotel on Národní street.

Among the most well-known realizations of the studio is surely the reconstruction and extension of the synagogue in Smíchov (2004) or the reconstruction of the administrative building of the Jewish Museum in Prague - interiors of the library, archives, and research room (2000). However, readers of Archiweb probably also noticed the new construction of a family house on Verdiho street in Prague, recreational house Pouště, or villa in Horní Počernice (all in 2006). Especially in recent years, the architects had the opportunity to engage in larger hotel projects: the reconstruction of a building for this purpose in Senovážné náměstí (2006) and the aforementioned new hotel construction on Národní street (in the zoning process).

HOTELS

In recent years, you have repeatedly focused on hotel design. By the way, when you arrive in another city, do you stay in a hotel?Richard Sidej: Personally, I do not prefer hotels. To me, hotel service is limited to a place to sleep, a place where it doesn’t rain, and a reasonably accessible location. I don't seek more. Or maybe at my age, I can't enjoy and savor it. As an architect, I design hotels according to standards that I, as a client, do not use myself.

Juraj Matula: … it is the same as when you design a whirlpool for an exclusive interior. I have never sat in one. To design a ski jump, you don’t have to necessarily jump 110 meters on skis.

We had a client who had never built a hotel but was very well-traveled. However, it gradually became apparent that this user knowledge was more of a hindrance. He did not perceive the hotel as a complex. The background and services form a significant part of the project. His attention was scattered over individual experiences, and then the author had to scratch ideas and explain why they couldn't all be used in the design.

|

R. S.: There is a relatively fundamental difference between a five-star and a four-star hotel. A five-star hotel carries more classic standards and definitely more conservatism. It must correspond to the approach of five-star clientele.

J. M.: All categories of hotels basically provide the same service: overnight stays. However, they differ in additional services provided. There is a growing disproportion between the area of the background and services, both volumetrically and operationally and financially. And also the demands on staff: in a five-star hotel, the ratio of guests to staff is nearly 1:1. Lower categories do not bring such significant differences, but five-star is a leap.

Does the mentioned conservatism also influence the formal aspect of architecture? Is it present in the assignment?

J. M.: I think not with the object as such. If current managements require something, then it is the presence of something "Prague-like". Whether it’s the uniqueness of cubism or anything else that is hard to define…

Is there something "Prague-like" in the project for the hotel on Národní street?

J. M.: The type of five-star hotel is significant in the city as something more than just an accommodation facility. This is precisely due to a large portion of background: a congress hall, restaurant, meeting rooms. The building thus offers significant public usage, further enhanced by its location in such an important area. Therefore, the object effectively becomes a public building, a meeting place - albeit primarily associated with business. In this sense, I believe that one can find a type characteristic of the city. We therefore conceived the object as a palace, a solid-looking building that would represent public significance with dignity - and at the same time be characteristic of Prague. We leaned towards these ideas because we are building in the historical center. However, this does not mean that we have resigned on modern expression…

R. S.: Traditional urbanism, a non-experimental way of infill, focusing on the mass of the building itself. I think this is part of five-star: to integrate, to blend elegantly, to not exhibit.

J. M.: Specifically on Národní, one needs to look at the surroundings: there is the National Theatre, a church, a department store - these are archetypes. And the same way we sought an archetypal expression for our hotel. We found it in a representative building of a palace type.

|

R. S.: Undoubtedly yes. In design and technical equipment, it probably isn't. The situations occurring in hotel rooms have historically remained quite similar. But there are certainly different types of hotels set for different clientele. And specifically in those where people spend nights one or two at a time, in obligatory modular networks, I personally see possibilities in intertwining, such as loosening the modulation of residential units. To increase the degree of distinctiveness and reduce homogenization, repetition, similarly resolved floors.

In the Czech Republic, it seems to me that we lack a whole "group" of accommodation where the stay itself is an experience. And in this, I see a significant will. More so than in hotels, where everything is necessarily short-term, I am interested in this topic in residential buildings. In complexes equipped with high standard services, where my desire is not for a separated villa in Prague 8, 9 or 10, but life in the center. Something like a house in which film character Hercule Poirot lives: where the service works, is not visible, and does not burden one's living space.

INVESTOR

You mentioned that in the Czech Republic, you believe there is a lack of a whole "group" of accommodation where the accommodation itself is an experience. Isn't such an investor lacking?R. S.: I wouldn’t say so; in any case, that person hasn’t visited this office. In twelve years, I have never worked for the state or a municipality. We have exclusively private clients.

Only private investors? But that’s not the intention, is it?

R. S.: No, not at all. Rather, it relates to the profile of the office and the references… For certain projects, at this age, you simply can’t get justly involved.

Is there an explanation?

R. S.: Theories exist…

J. M.: So far, we have fared better in private competitions than in state ones. Besides, you can model the private client. And then you hit the mark or not. But to model a jury? To model a multi-headed dragon? Or a prominent figure might become the head of the jury and sway the others. A private investor is always easier to read.

R. S.: I would say that there is definitely a certain direct proportionality between the composition and type of project and the length of the office's operation. But I believe that projects could evolve, also so that tasks do not terribly repeat.

|

R. S.: That’s not entirely the case. However, since we do not suffer from a shortage of work in the long term, we try to compete once, at most twice a year. The last two years have been exceptions because we have entered competitions more often. But we are not really competition types.

J. M.: We are fortunate that private clients already know about us and occasionally invite us to competitions: such as for a hotel in Senovážném náměstí, for a new hotel project on Národní street, or for the Hagibor senior home for the Jewish community… But we have also been invited to competitions for a villa in Horní Počernice, for instance.

A competition for a villa?

J. M.: The client contacts several studios and requests a concept based on which they will choose.

But that’s probably exceptional...

R. S.: Not really. Such a situation surprisingly repeats itself. We had to compete quite a bit for the villas.

J. M.: You get a template email sent to six other studios that people have found perhaps on Archiweb; it includes their rough idea and photos of the plot… Clients have learned quite a lot. And if the investor is serious about implementation, their approach from the very beginning indicates how they want to proceed. Such an investor, or developer, also wants to reward you from the start - to pay at least for the "drafting." They know that this way they will receive professional work.

R. S.: We try to avoid competing for free. It is clear from the outset that the client is not interested in investing in the project. The only reason could be some other strong emotional bond to the project.

|

R. S.: Hard to say. Besides visualization, maybe eleven to thirteen?

J. M.: Or you could say eight to sixteen…

R. S.: We are clear that we do not want to expand the office. The limit we experienced was 16 architects. After that, the structure of operation changes significantly. It's better to maintain a certain way of working and simply not take on more projects because you wouldn’t be able to finish them. Of course, we don’t know what the future holds; perhaps we won’t be able to avoid expansion, but we are certainly not aiming for it programmatically.

J. M.: We do not employ other professions besides architects. We have very strong ties with many other collaborators, often permanent ones, but they aren’t sitting here with us. We have never considered having a construction engineer here, for instance.

R. S.: Abroad, architects want to do execution drawings thoroughly themselves. Whereas we - although we do all stages of the project ourselves - take parts from execution drawings, from large construction units, from statics, only those aspects we are interested in: we draft facades, details, locksmith or carpentry products… But the basic construction work, excavations, or grading we cannot do as well as specialized structural teams. Not always is this division successful, but we are gradually trying to stabilize the system outlined.

TEACHER MIROSLAV ŠIK

When we talk about work systems, we cannot help but return to your school days at the Faculty of Architecture of the Czech Technical University. You studied under Miroslav Šik. How significant was that experience and do you still feel his influence, or the influence of New Czech Work today?J. M.: I was in his studio for two semesters, and I am sure that for each of the approximately 40 people who passed through his studio, it is individual. For me, Professor Šik's influence - that is, he scolded me recently for calling him Professor - is more on a personal level. In the sense of the relationship to work and the way of working, personal involvement in our crafts, and the idea that in our profession/calling, everything intersects from music through fine arts to sports or languages. It’s the same as with a doctor - even when they walk down the street, they are still a doctor. Of course, if a cornice falls, no one calls: Where is the architect? The connecting element, and for example, also the reason for the emergence of New Czech Work, was not so much the desire to continue in analog architecture, but rather the desire to continue in some kind of system that Šik established in the studio.

What did the work specifically look like?

J. M.: Perhaps it wasn’t even a way of working, but the essential investment of energy from the educator. When one struggled with a project over nights for weeks, they felt that during a one-hour consultation, they received an adequate return. However, this can probably work well in any other studio; it always depends on the personality of the educator. I believe that today his methods are reflected in several studios increasingly sought after by students at the Faculty of Architecture. Anyone interested in discovering how work was done under Miroslav Šik should enter the studio of Honza Šépka. In that respect, Hájek and Šépka do well - I saw their work last year when I was on the jury of the Olověný Dušan competition. That is, I saw the results, but I believe that the atmosphere must be quite similar. Also the same graphics, same views - an effort for comparability…

Šik had a well-developed system of working with people in the studio, complemented by a high degree of preparedness of the task assignment: in parallel with studio work, thematic lectures were held. Students also learned a lot from each other. Perhaps he didn’t say this precisely, but I remember that he essentially urged us to steal ideas from each other. Just the fact that I evaluate a solution as good and want to use it myself is a learning process. But it wasn’t a leftist collective approach, no qualitative measure - as might seem now - after all, he clearly ranked work from one to seventeen.

What you said evokes the impression of great discipline…

J. M.: Sometimes the others laughed at us, saying that the system was military-like. We all sat, the doors were closed, the first one came in, consulted, everyone's sat and watched, and the relevant person had to hang their work on the wall down to the last small piece of paper… And it was precisely specified what was consulted when: hundreds, fifties… If you weren't properly prepared, you lost your consultation. On the one hand, the approach may have appeared military, but on the other hand, the discipline was useful: the method led us to adhere to order and continuous work.

|

R. S.: Martin and I attended only consultations when he was no longer leading his studio at school, and people from New Czech Work were dispersed across other studios.

What memories do you have of school? Did you encounter similar strong personalities at the faculty or in practice?

R. S.: I certainly tried to choose studios based on their leaders, to know to whom and for what assignment I was going. Among our local professors, I always intuitively preferred those who actively build houses, not just teach. But I also have the feeling that sometimes an hour-long conversation, a good article, or a lecture can shift a person comparably to a painstakingly outlined project. In the last two years of our studies, we essentially only went “to work.” I remember very much looking forward to leaving school and having everything really begin. I certainly couldn’t say that if school fully fulfilled me and it was wonderful, enriching studies. I feel that for many things, one necessarily came only as a self-taught person: by trial and error. I know that at first, I personally found it suspicious to graduate from school with usually little practice and immediately do "on my own." In retrospect, I regret nothing; those were interesting years, and a clearly right choice. Today, few are willing to start for three thousand crowns a month. Many students have clear financial expectations about how they want to start and what standard they want to maintain.

Thanks to several projects, such as the Smíchov synagogue or the reconstruction of the administrative building of the Jewish Museum, you are sometimes associated with the Jewish community...

R. S.: The mentioned projects were done for the Jewish Museum; we won the competition for the reconstruction of the administrative building as relatively young architects, and it is true that it helped a lot with the startup of the office. We also worked on two other projects for the museum. But then came the floods… As someone from Brandýs, I should mention that we also did a study for the reconstruction of the synagogue in Brandýs nad Labem. I was very much looking forward to it, but then the floods came… the client's situation changed profoundly, and two days before signing, the project was canceled. But for the Jewish community, we only competed once - for the Hagibor senior home and did several truly minor works: the adjustment and reconstruction of the winter prayer room and adjoining areas in the Jubilee Synagogue in Jeruzalémská street, a loft extension on Roxy… For instance, architect Šantavý did a completely different and much larger amount of work for the Jewish community. Thus, I do not consider myself successful in these "home fields" at all…

Thank you for the interview.

Kateřina Lopatová

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment