Interview with HŠH architects

|

The First Decade

Jan Kratochvíl: Your entry into architecture was very striking, even meteoric, in the second half of the 1990s. Something like this hasn’t happened to anyone else. Do you think your “record” could be repeated? Can a group of twenty-five-year-old architects break through the barriers of the field today?Petr Hájek: I think it is still possible to break through at twenty-five today, why not? It will just be tougher and the path will probably not go through architectural competitions. Current legislative conditions do not allow for a larger commission to be entrusted to someone who has no experience yet. Today, investors require such guarantees and references that only large design offices can fulfill them. And that’s bad, because in such an environment, it is very difficult for young architects to establish their own office.

Tomáš Hradečný: But it is possible. For example, through a temporary connection with a reputable office. The important thing is to endure.

Jan Šépka: The time when someone was willing to entrust architecture students - that is, completely inexperienced people - with a significant commission after winning a competition is probably gone. The 1990s offered such an opportunity, as politicians and society were in their beginnings. It was a time when principles and rules wanted to be adhered to. The situation, of course, changed rapidly after 2000, mainly due to the experiences of politicians and their nimble maneuvers in the laws.

If a young architect knocked on the door of your studio tomorrow, wanting to temporarily join a reputable office, would you provide him protective wings?

Tomáš Hradečný: Not universally, but it ultimately depends on the specific situation and context. We would definitely seek a way to be helpful so that the author of a quality proposal could continue working.

Did you plan to work in some studio after school, or did you want to immediately establish your own?

Tomáš Hradečný: Thanks to the competitions we won, we had the opportunity to work on our own commissions. It needs to be mentioned that we initially did not work only as three but even as six. Some of us did not want to face all the pitfalls and risks that come with setting up an office, so they preferred to go to work in another office with prospects. In the end, we remained three.

|

Jan Šépka: Yes, it was a hard school. We did not expect to win the competition at all and we were truly taken aback by such a situation. Especially since negotiations about further project documentation and, of course, realization immediately started after the competition. At that time, we knew almost nothing about designing, but the prospect of working on our own project attracted us so much that we naively signed all contracts and threw ourselves into everything headfirst.

Petr Hájek: I think it was also a hard school for the investor, who had no previous experience with a project from a competition design. Many negotiations happened confusedly and without continuity in previous decisions because of that. In the end, we had to fight for the realization by exerting authors' rights.

What all needed to be done for you as fresh graduates without authorization to realize such a construction?

Jan Šépka: First of all, we had to turn to a more experienced colleague with an authorization stamp who was willing to endorse our first project.

Tomáš Hradečný: It was also necessary to quickly rent an office and create an environment for joint work.

Do the connections from founding the studio carry over to the present? Is your studio different from the studios of colleagues who have brought habits from their previous workplaces into their own studios?

Tomáš Hradečný: I would say yes. We do not share much in common with the structure of a typical private firm with precisely defined internal hierarchy - for better or worse. We actually do not know the internal environment of other studios. In any case, in our studio, a person is responsible for themselves and for the whole studio at the same time - there is no one to hide behind.

Teaching and Learning

Since 2004, you have been teaching architecture at the FA in Prague. What led you to this step?(more about the studio of Petr Hájek and Jan Šépka at www.hsatelier.org)

Jan Šépka: In 2004, we were approached by the former dean of the faculty, Professor Šlapeta. We gave a lecture about our work and subsequently started leading a studio in the winter semester. Šlapeta tried to bring young architects to the school and he succeeded.

Petr Hájek: Even before that, we had the experience of the summer Liberec school, which Monika Mitášová brought us to. There we first realized that we would be interested in working at school.

Do you believe there is such a thing as "maturity" to become a teacher? Conversely, is there a "overripeness" when one should no longer be a teacher?

Petr Hájek: It’s like with any other creative work that you enjoy and try to devote yourself to it as much as possible. There may come a moment when you feel you are starting to repeat yourself and do not have anything to offer. Then it is good to leave, but only a few can do that.

Jan Šépka: The school is primarily about the discussion between the student and the teacher. The answer to your question would probably be better handled by the students themselves, but I perceive it purely subjectively such that if the discussion exists and is fruitful, then the teacher-student relationship works, regardless of whether the teacher is not yet mature or is conversely overly mature. Discussions - questions and answers - should be beneficial for both sides. I feel that at our age, students see us as somewhat older colleagues, and thanks to that, they do not have a problem discussing with us.

How is teaching at FA ČVUT for you? What is the situation like at the school?

Petr Hájek: If we can judge from school exhibitions and diploma commissions, the level is very uneven. Top works go alongside below-average ones. Assessments are unbalanced. There is no bar against which to measure the quality and level of the school as a whole. There is a lack of competitiveness among studios and competition among educators.

How does teaching specifically progress in your studio?

Petr Hájek: Teaching is based on all students working on one task. It is submitted in uniform formats and the final assessment is conducted with the participation of invited guests. These are architects and architecture theorists whom we respect.

I noticed that you assign topics that combine multiple functions together. Is that intentional?

Jan Šépka: We try to combine two or more functions together, such as tram - housing, stadium - supermarket - multiplex - housing, park - multifunctional object, highway - city. We intentionally select contradictory functions that can influence each other and transfer their established forms to other functions. We want students to engage with these relationships between several different functions.

What is the outcome of this method of conflicting functions?

Jan Šépka: Today, we are witnessing a whole range of games with facades, with materials that exist, but in most cases are completely formal. Similarly, the shaping of houses, primarily due to new technologies and materials, is now at a point where I can do completely everything, but ultimately, it is only a formal game with shape. That has no connection with function and ultimately not even with the interior, as, for example, Gehry demonstrates.

Petr Hájek: The connection of contradictory functions in the assignment allows us to look at typology and architecture from a different angle and to seek new solutions. We teach more a "method of work" than any universal recipe for doing architecture.

|

Jan Šépka: Our teachers - for me it was Miroslav Šik, for colleague Hájek it was Alena Šrámková, and later at the Academy, Emil Přikryl, where we met together - certainly played a significant role. We always preferred to work on one topic for one semester because that allowed us to discuss projects among ourselves. Comments from colleagues - students were sometimes more inspiring than the professors' remarks. This eventually led to joint meetings and discussions among us even after Miroslav Šik's departure from the faculty. And the result was, in fact, the exhibition and catalog New Czech Work in 1994, which marked a kind of culmination of our school discussions.

Petr Hájek: Even though the schools of Alena Šrámková, Emil Přikryl, and Miroslav Šik were different and used different teaching methods, they had one thing in common: they showed a way of thinking about architecture and inspired many young people to work as architects. Our current work builds on this experience, and we have the same goal, but the means are different. We teach architecture based on specific assignments that contain two contradictory elements. Based on this tension, we seek questions and answers with the students.

Jan Šépka: Combining multiple functions within one object arises from our work on the Prague 2000 project, where we tried to connect the city with the transportation ring around Prague. The entire project was a vision that dealt with the city's boundaries, preventing its constant expansion into the countryside, and the planned and partially built express ring served to that end.

Sometimes academic experimentation encounters limitations and problems of specific places in real practice. How significant is the phenomenon of place in your assignments?

Jan Šépka: The place is also important. The places we work with now are spaces where trams run, stadiums, parks, or highways, meaning they are defined today. This defined place, along with functions, is another factor that helps students find a concept. In fact, it is most challenging to work on a project where you have no limitations and are building on a green meadow. Therefore, because of the limitations, we try to help students in their thinking about the assignment.

Archdiocesan Museum

When you drew the competition design for the Archdiocesan Museum, did you feel that your idea could win?Tomáš Hradečný: When we submit a design for a competition, we believe that we could win. Otherwise, we wouldn't submit our design.

In which competitions have you not submitted designs?

Jan Šépka: For example, in the competition for the Janáček Philharmonic in Brno. Our approach to competitions is essentially a variant analysis, from which we choose the best one. For the philharmonic, we had, I believe, around sixty different conceptual variants, but none of them seemed good to us in the end.

Did any variant resemble Pavel Joba's winning design?

Petr Hájek: Yes, in the urban solution. We found other counterparts to our variants as well. In architectural competitions, several designs with similar concepts can sometimes emerge. What qualitatively distinguishes them is the elaboration of the original concept in the details of the design.

What about the competition for Dolní náměstí in Olomouc and others where you did not receive any awards?

Petr Hájek: In the competition for Dolní náměstí in Olomouc, the design that incorporated all the principles and ideas from Horní náměstí won, including our furniture. Compared to us, it had one advantage - we were not the ones who submitted it.

Jan Šépka: To add: The Olomouc city hall does not want further discussions with architects, as it did with us at the time regarding Horní náměstí. Today, it demands that Dolní náměstí look the same as Horní, but needs someone to do exactly what the city hall tells them.

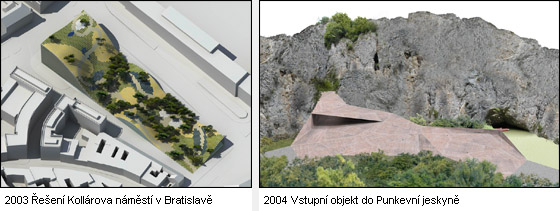

Tomáš Hradečný: Other unsuccessful competitions were, for example, for Kollárovo náměstí in Bratislava or the entrance object to the Punkevní caves. However, these projects have pushed us forward in our work, even though they did not receive any awards. We also participate in competitions because we have the opportunity to shape our vision of the design without significant limitations.

|

Without significant limitations? You still have to adhere to the competition conditions, which are a clear limitation.

Petr Hájek: In my opinion, sometimes it is better to risk exclusion with a good design than to compete within prescribed limits with a bad one.

Jan Šépka: But architecture is about limitations. Architecture is the least free art of all, and it forces many people to think and overcome boundaries and limitations. That is probably what we enjoy about architecture - overcoming boundaries.

Speaking of overcoming boundaries, do you have ambitions to establish yourselves abroad? Do you think Czech architects have a chance to succeed in international competition? What paths could lead to that?

Tomáš Hradečný: Czech architects will have a chance abroad once Czech architecture is known there. That is not the case yet.

Jan Šépka: For someone to significantly break through abroad today, it is not enough to simply be a creative architect; one must propagate their work, give lectures, participate in international competitions, and similar events that lead to visibility. Many well-known foreign offices have teams of people who take care of their promotion. The question is whether such a path is the right one.

Let’s return to the Archdiocesan Museum. The museum is based on inserting modern contrasting elements into the existing structure. Does this concept come from Italy or Spain?

Jan Šépka: Certainly, but a similar principle can also be found in Central and Northern Europe. A few years ago, we visited the Archbishop's Museum in Hamar, Norway by Sverre Fehn, which has a similar concept, however, the contrasting principle is not as consistent as we applied in the museum.

Some of your colleagues criticize the consistency of your concepts.

Tomáš Hradečný: One can criticize inconsistency more. I would value correctness or incorrectness, appropriateness or disproportion in relation to the whole and only then to the detail or partial function on the concept.

|

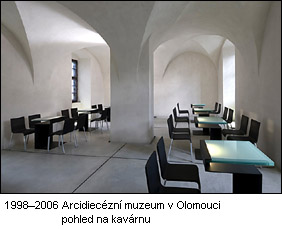

Jan Šépka: The café must have the same form as the museum because it is part of it. Some people find it too austere, but there are many similar cafés even here, which are not adorned with pictures and other superfluities. We see the mistake primarily in the museum's interest, which does not promote the café at all and has not yet allowed for direct access and the end of the exhibition right in the café. That is a great pity because most museums offer the possibility to sit in a café or restaurant at the end of the visit. The café space is primarily lacking people.

What are the biggest changes from the realized version compared to the competition design?

Petr Hájek: It was not about conceptual changes but about the presentation of some findings that entailed operational changes. In such a demanding building, one must reckon that during the work, elements will begin to appear that you could not have anticipated. Restorers began to find valuable inlaid floors and paintings beneath modern layers. The archaeological research also uncovered many interesting findings that we wanted to present. Thanks to these findings, for example, we moved the café from the space where decorated ceilings were found and dedicated this space to temporary exhibitions.

Moving Forward

The Archdiocesan Museum will receive numerous awards and recognition, but architects do not dine on those, and they usually do not lead to further commissions. In recent years, you have narrowly missed victories in competitions. Do you actually have enough work today?Tomáš Hradečný: Primarily, due to the intense oversight of the museum, we have actually lost many projects. But that’s a price one must consider.

Petr Hájek: It is common that when you successfully complete a job, it brings you new contacts and new commissions. After the completion of the paving of the square in Olomouc and at Prague Castle, we were categorized as pavers and received several commissions to modify public spaces. After completing the first phase of the museum and the house in Beroun, no one besides journalists has reached out yet. Our architecture may be interesting to many investors, but on the other hand, it is also complicated and, as already mentioned - radical. It is also true that we have not been successful in any competition lately.

|

I see that you are working on a competition proposal for the National Library. Will you submit it?

Tomáš Hradečný: We will submit it.

What other projects are you currently working on?

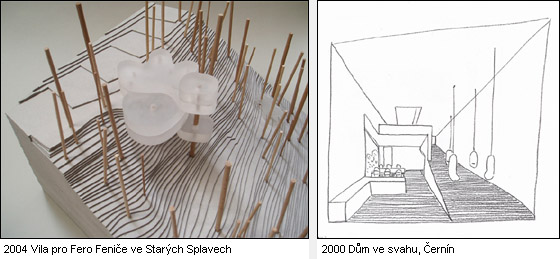

Jan Šépka: Since 2000, we have been trying to build a family house in a Protected Landscape Area on Křivoklátsko with a client. After nearly six years, we will likely receive a building permit. This house relates to the exhibition Spatial House and reveals the possibility of a residential spiral space. Another project is a small apartment building, where we continue to contemplate the collaboration of clients on the final form of the building. The house, like the one in Beroun, has a spatial structure that the specific owners will fill according to their preferences.

A spiral residential space - that sounds like the raumplan of the Müller villa. Soon we will recall the hundredth anniversary of Loos's "discovery."

Jan Šépka: The family house in Černín references Loos's raumplan in a way, but in our case, it is a consistent continuous spiral from the basement to the top floor. The house is located on a steep southern slope, the inclination of which we repeated inside the building. Throughout the house, you will alternately transition from a sloped ramp to a horizontal surface. The sloped surfaces are not self-serving - the client has a large film collection and invites not only many friends to screenings but one can talk about small film festivals. These spaces will serve as projection rooms with sloped surfaces.

|

Do you think the architectural space is evolving? What could be today's contribution to the issues of architectural space? Is there development in architecture? Did Loos actually discover raumplan or did he just name one of the existing principles of shaping space and thus appropriated it?

Jan Šépka: We addressed various spatial principles conceived within buildings in the Spatial House project. It was a recapitulation of spatial possibilities, where we realized that recently it has not been possible to come up with something completely new. And it is quite possible that principles such as assigning, inserting, intersecting spaces, or continuity of space, both vertically and horizontally, are exhausted. Architecture and its development have always been greatly influenced by new discoveries or situations in society. I believe that transport and the densification of our cities may still play their role. If I take shots from science fiction films, like in Blade Runner, then I must realize that not only spatial but also many other aspects can change radically. And that could evoke new possibilities, not only in architecture.

Petr Hájek: In this context, it is worth mentioning projects that deal with the combination of real and virtual space. These projects are currently emerging outside of architecture in the planning of interplanetary flights. Virtual space must satisfy the "need for space" in constrained conditions and partially replace the real space. I can imagine similar principles transformed into architecture.

|

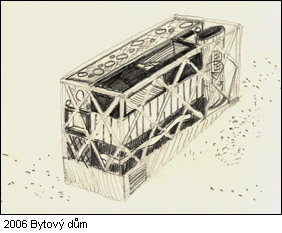

Petr Hájek: The building is essentially a vertical plot - a spatial parcel. The load-bearing structure forms the framework for constructing six apartments - objects. The client is absolutely involved in the design. They decide on materials, layouts, shapes, and therefore also on the architecture of the house. Otherwise, it is similar to when you are designing six family houses for six different clients. Each of them has different requirements, which enter the design. The difference is that here they intersect in one object.

Jan Šépka: We become merely drawers and executors of any wishes from the clients.

With the apartment building project, I recall the thought of Louis Kahn: "A home is a house and its inhabitants. It changes with each inhabitant. The client for whom the house is designed determines the necessary dimensions of the area. The architect creates spaces from these required areas. If such a house, created for a certain family, is designed truthfully towards form, it must also be good for another family." Would you try to refute this statement and defend the client's presence on the playground?

Petr Hájek: I think our apartment building will also be good for any "other" family. It allows for rebuilding according to new ideas both in the interior and exterior, without changing the essence of the house after such an intervention.

Tomáš Hradečný: There is probably no universal form of good family housing today. The mentality of builders usually stems from the mistaken idea that enjoying freedom, they can afford everything that best suits their individuality (and not the family): deodorant, razor, hair color, breasts, insurance, vacation, car, and of course housing. Families do not want to consciously limit their individuality in order to obtain benefits from sharing common "urban" spaces; rather, they consume products in the form of hollow villas made from the cheapest materials offered to them by an incredible number of commercial magazines and real estate agencies. All these products have, with few exceptions, one thing in common: huge profits for crafty developers and construction companies on one side, littered countryside, traffic jams, and social vacuum on the other. A significant role in this unfortunate state plays the very low level, lack of concept, and incompetence of individual representatives of state administration at both central and municipal levels, who simply confuse public interest with their own. But we are getting into the inheritance of Bolshevism…

Thank you for the interview, and I look forward to our next meeting.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment