The housing galaxy is built from eight types

The first part of the interview with Martin Hejl, the curator of the exhibition

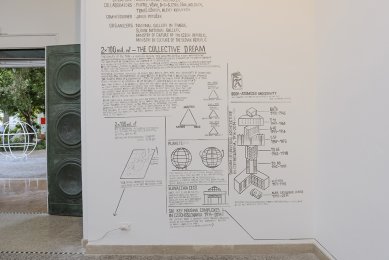

2 x 100 mil.m² : The Collective Dream

To start, I would like to ask about the process of preparing the exhibition, who was involved in it, how the research was conducted in the Czech Republic, and how Rem Koolhaas influenced the preparation with his main thesis for the biennale?

We started competing last summer. After two months of work, we created a basic approximately 160-page brochure as the first research document that originated in our studio Kolmo, with which we won the competition for the curator of the Czechoslovak Pavilion 2014. In the final phase of preparing the brochure, we tried to contact as many institutions as possible because we knew that if we were to deliver the theme Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014 credibly and qualitatively, we would need a fairly decent research team. This means a large number, with access to as many archives as possible, and with the utmost intelligence.

What questions did you address in your research and with whom did you collaborate?

At the very beginning, we debated a lot about what the theme should be, and we approached it extremely, almost dogmatically responsibly. We truly considered it a challenge that would be practical for our region to adhere to the years 1914-2014 and cover the entire one hundred years. Exceptional groups typical to Czech architecture, such as functionalism, the avant-garde of the 1930s, or even the subsequent 1960s quickly emerged from that. It would be a fragmented statement based on our aesthetic preference. In this sense, we were more ambitious and searched for a story that could be told coherently, that has some outcome and broader validity across the entire century. At that moment, we decided to focus on several different architectural programs, including housing. Housing and sacred buildings made it to the finals, and in the end, we decided to go with housing because the story is bigger, has a stronger impact, and needs more attention today than the others. We approached our studio at FUA TUL in Liberec, and we managed to collaborate with the studio of Jan Studený and Benjamín Brádňanský from VŠVU in Bratislava. This collaboration opened new possibilities for interpreting our shared history. Once we won the competition, we launched research at both universities and gradually pulled more people into the team. We approached Cyril Říha as the editor of our work because we were aware that the amount of data that would go through our hands was extremely large, and there are many people involved in the whole process, so it would be challenging to maintain a coherent intellectual line. Cyril showed extreme dedication and provided excellent intellectual help and criticism. Then suddenly, I was contacted by the guys from the d-g-g architectural studio in Prague, who work at ČVUT, and thus we gained access to archival materials from IPR and ČVUT, etc., as a source of historical materials in the book. In Slovakia, Peter Stec and his studio joined us, providing a fantastic study on how and with what to create prefabricated housing estates. These are the main components that we orchestrated to together create one symphony.

How would you define your concept of generic or universal architecture?

For a long time, we were debating individual vs. collective, but in the end, it became clear that we needed to name the actual substance we were dealing with. This was heavily manifested in the map of 200 million m² of housing in Czechoslovakia, where residential complexes built over the last hundred years are marked in 56 cities. Subsequently, we identified six highlights, axonometry, which shows six basic urban patterns. This is complemented by an element that we call the totem, a diagram of evolution from standardization to prefabrication to cataloging. The moment the totem stood on the map, we realized that the galaxy of housing is mostly built from those eight types we have in front of us. This is the abstraction of our reality that we inhabit. At that moment, we decided to start naming. Universal architecture is the fundamental substance that forms the city; most of what we inhabit, architecture without the avant-garde, is the basic template. It is surprising how little diversified it is over a hundred years in Czechoslovakia, both typologically and structurally.

The theme of the biennale is Absorbing Modernity, and one of the layers is indeed national identity – how was national identity absorbed by modernity, or where is national identity in modernity – is there any place for Czech or national identity in your concept of universal architecture?

I think that what we are showing could stand anywhere. Ironically, it is interesting that some of the constructions we exhibit are also displayed in the Chile Pavilion. There is a notion of soviet bloc, which is absurd because some constructions actually emerged from our development, while some arose in other countries; yet, synergistically, the post-war period of the 20th century, despite the political differences between the capitalist world, such as France, and the communist world behind the Eastern Bloc curtain, synchronized. The need for an increase in housing standards and rapid construction was clear, and national identity did not play a role there. Perhaps the only city that truly had national identity in its shield is Ostrava Poruba, which searched for a national style, but ironically, it is a copy of the Stalinist style imported from Russia. I do not believe we are showing something specific to Czechoslovakia. In this sense, I have some doubts about whether this concept still makes sense. A country with ten million inhabitants, seventeen including Slovakia, is the size of one large city. I do not think national identity is a concept that has validity in a global society. The universal architecture we depicted constitutes 97 percent of the housing built in the last 100 years, which accounts for 90 percent of all housing in our country. This indicates that this rhetoric is outdated.

So does national identity seem to you more of a nostalgic moment?

It is partially evident in those pavilions. We have a pavilion from 1926 that is shared, Czechoslovak, and there is a peculiar alternating of the two states that we tried to erase and create a directly Czechoslovak collaboration. That pavilion refers to the exhibition space in Mánes in the Czech Republic, to the avant-garde, although it is more monumental, but it is completely dysfunctional and is extremely constraining as a building. Anything exhibited in it nowadays is inflexible; you cannot drill into it, demolish it, and so on. It is a peculiar memorial approach. This is how we talk about architecture, and I believe this is a big problem. We keep nostalgically looking back at the 1930s, at the avant-garde – sure, back then we were the sixth or seventh richest country in the world, which means villas like Villa Tugendhat were built, costing then the price of seven villas in Ořechovka, which is no longer the case; at the same time, in the 1960s, when we managed to formulate our architectural aesthetics for a moment. But these are still immensely isolated groups. The main story of the cities, the urban substance, is not the story of these unique architectural buildings.

What is the concept of the exhibition and the installation? At first glance, your presentation is quite austere, and when you open the book, it is full of stories.

What you are saying was intentional. I wouldn’t say the installation is austere; I would say it is straightforward. We suspected that if we were to focus on this fundamental substance, we would not end up with a pavilion full of extravagant models that are extremely seductive and diverse, etc. Therefore, we decided to concentrate this color and diversity into one object, which is the book. We formulated the pavilion as a reading room and exhibited three main elements – a map of the two states with 56 cities, on which traces of housing built over the last hundred years are marked – it is evident that when you walk across the map, the patterns of housing are quite similar. From this multitude, we isolated six basic patterns that we organized consecutively. They tell a story from individual housing in Baťa’s houses through collective housing, its evolution, to the subsequent contemporary catalog suburbia. It is an evolutionary spiral. Throughout the process, we invited several theorists, artists, and designers to criticize our work and the exhibition to avoid typical oversaturation and manage to get to some clear information.

Could you briefly say what feedback you have received about the pavilion?

During the opening of the pavilion, the feedback was excellent; I presented the pavilion to a number of people, from Rem, through the research team of OMA, Ippolito, who did Monditalia in the Arsenale, Stephan, who did Elements in the central pavilion, as well as curators from other countries and journalists, and the feedback was more than good. Surprisingly for me, I expected that the theme and the book would resonate a lot towards the east; I anticipated it would work for Russia, Poland, Romania, etc., but to my surprise, the pavilion also received feedback from South American countries or countries like Korea, etc.

I would also like to return to other artifacts in the pavilion – we found that in the 1970s, 2-4% of the budget always went to art in public spaces. We found it interesting to use this rule and contact Tomáš Džadoň according to the same assignment to interact with our exhibition. He came up with the idea that we could work with a sign, and in the end, we settled on swapping Cecoslovacchia for Slovacchiaceco. This is a certain reminder that the pavilion is dedicated to Czechoslovakia for the first time, despite the fact that Czechoslovakia split into two independent states. A small detail is the two children's climbing structures that were prefabricated and manufactured in thousands of series, present in every kindergarten and school from 1965 to the early 1980s. We couldn’t find out who the author was. We had two pieces restored, transported them to Venice, where they serve, and subsequently they will be returned repaired to the children. To connect the book with the pavilion, so that the synergy between these two carriers of information is sufficient, we asked Alexej Kluykov, who is the author of the illustrations in the book, to write captions for the individual exhibited elements in the pavilion.

For us, the main question is what the role of the architect in society today is, when it is clear that the field for architecture is shrinking. Therefore, the subtitle of the book is 'atomized modernity' – there is a certain disintegration of grand ideas, large architectural firms, which are fragmenting into architectural studios with just a few people who do not have the stamina to have a bigger voice in society. Society fills this gap with quick solutions like catalog houses. The question is whether the profession of architect as such, as we know it, which we are aware of, is disappearing today in the position of designer on one hand or as an artist on the other, can survive and whether it even still exists, whether architects are perhaps dead and whether this is purely a peculiar nostalgia.

2 x 100 mil.m² : The Collective Dream

To start, I would like to ask about the process of preparing the exhibition, who was involved in it, how the research was conducted in the Czech Republic, and how Rem Koolhaas influenced the preparation with his main thesis for the biennale?

We started competing last summer. After two months of work, we created a basic approximately 160-page brochure as the first research document that originated in our studio Kolmo, with which we won the competition for the curator of the Czechoslovak Pavilion 2014. In the final phase of preparing the brochure, we tried to contact as many institutions as possible because we knew that if we were to deliver the theme Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014 credibly and qualitatively, we would need a fairly decent research team. This means a large number, with access to as many archives as possible, and with the utmost intelligence.

What questions did you address in your research and with whom did you collaborate?

At the very beginning, we debated a lot about what the theme should be, and we approached it extremely, almost dogmatically responsibly. We truly considered it a challenge that would be practical for our region to adhere to the years 1914-2014 and cover the entire one hundred years. Exceptional groups typical to Czech architecture, such as functionalism, the avant-garde of the 1930s, or even the subsequent 1960s quickly emerged from that. It would be a fragmented statement based on our aesthetic preference. In this sense, we were more ambitious and searched for a story that could be told coherently, that has some outcome and broader validity across the entire century. At that moment, we decided to focus on several different architectural programs, including housing. Housing and sacred buildings made it to the finals, and in the end, we decided to go with housing because the story is bigger, has a stronger impact, and needs more attention today than the others. We approached our studio at FUA TUL in Liberec, and we managed to collaborate with the studio of Jan Studený and Benjamín Brádňanský from VŠVU in Bratislava. This collaboration opened new possibilities for interpreting our shared history. Once we won the competition, we launched research at both universities and gradually pulled more people into the team. We approached Cyril Říha as the editor of our work because we were aware that the amount of data that would go through our hands was extremely large, and there are many people involved in the whole process, so it would be challenging to maintain a coherent intellectual line. Cyril showed extreme dedication and provided excellent intellectual help and criticism. Then suddenly, I was contacted by the guys from the d-g-g architectural studio in Prague, who work at ČVUT, and thus we gained access to archival materials from IPR and ČVUT, etc., as a source of historical materials in the book. In Slovakia, Peter Stec and his studio joined us, providing a fantastic study on how and with what to create prefabricated housing estates. These are the main components that we orchestrated to together create one symphony.

How would you define your concept of generic or universal architecture?

For a long time, we were debating individual vs. collective, but in the end, it became clear that we needed to name the actual substance we were dealing with. This was heavily manifested in the map of 200 million m² of housing in Czechoslovakia, where residential complexes built over the last hundred years are marked in 56 cities. Subsequently, we identified six highlights, axonometry, which shows six basic urban patterns. This is complemented by an element that we call the totem, a diagram of evolution from standardization to prefabrication to cataloging. The moment the totem stood on the map, we realized that the galaxy of housing is mostly built from those eight types we have in front of us. This is the abstraction of our reality that we inhabit. At that moment, we decided to start naming. Universal architecture is the fundamental substance that forms the city; most of what we inhabit, architecture without the avant-garde, is the basic template. It is surprising how little diversified it is over a hundred years in Czechoslovakia, both typologically and structurally.

The theme of the biennale is Absorbing Modernity, and one of the layers is indeed national identity – how was national identity absorbed by modernity, or where is national identity in modernity – is there any place for Czech or national identity in your concept of universal architecture?

I think that what we are showing could stand anywhere. Ironically, it is interesting that some of the constructions we exhibit are also displayed in the Chile Pavilion. There is a notion of soviet bloc, which is absurd because some constructions actually emerged from our development, while some arose in other countries; yet, synergistically, the post-war period of the 20th century, despite the political differences between the capitalist world, such as France, and the communist world behind the Eastern Bloc curtain, synchronized. The need for an increase in housing standards and rapid construction was clear, and national identity did not play a role there. Perhaps the only city that truly had national identity in its shield is Ostrava Poruba, which searched for a national style, but ironically, it is a copy of the Stalinist style imported from Russia. I do not believe we are showing something specific to Czechoslovakia. In this sense, I have some doubts about whether this concept still makes sense. A country with ten million inhabitants, seventeen including Slovakia, is the size of one large city. I do not think national identity is a concept that has validity in a global society. The universal architecture we depicted constitutes 97 percent of the housing built in the last 100 years, which accounts for 90 percent of all housing in our country. This indicates that this rhetoric is outdated.

So does national identity seem to you more of a nostalgic moment?

It is partially evident in those pavilions. We have a pavilion from 1926 that is shared, Czechoslovak, and there is a peculiar alternating of the two states that we tried to erase and create a directly Czechoslovak collaboration. That pavilion refers to the exhibition space in Mánes in the Czech Republic, to the avant-garde, although it is more monumental, but it is completely dysfunctional and is extremely constraining as a building. Anything exhibited in it nowadays is inflexible; you cannot drill into it, demolish it, and so on. It is a peculiar memorial approach. This is how we talk about architecture, and I believe this is a big problem. We keep nostalgically looking back at the 1930s, at the avant-garde – sure, back then we were the sixth or seventh richest country in the world, which means villas like Villa Tugendhat were built, costing then the price of seven villas in Ořechovka, which is no longer the case; at the same time, in the 1960s, when we managed to formulate our architectural aesthetics for a moment. But these are still immensely isolated groups. The main story of the cities, the urban substance, is not the story of these unique architectural buildings.

What is the concept of the exhibition and the installation? At first glance, your presentation is quite austere, and when you open the book, it is full of stories.

What you are saying was intentional. I wouldn’t say the installation is austere; I would say it is straightforward. We suspected that if we were to focus on this fundamental substance, we would not end up with a pavilion full of extravagant models that are extremely seductive and diverse, etc. Therefore, we decided to concentrate this color and diversity into one object, which is the book. We formulated the pavilion as a reading room and exhibited three main elements – a map of the two states with 56 cities, on which traces of housing built over the last hundred years are marked – it is evident that when you walk across the map, the patterns of housing are quite similar. From this multitude, we isolated six basic patterns that we organized consecutively. They tell a story from individual housing in Baťa’s houses through collective housing, its evolution, to the subsequent contemporary catalog suburbia. It is an evolutionary spiral. Throughout the process, we invited several theorists, artists, and designers to criticize our work and the exhibition to avoid typical oversaturation and manage to get to some clear information.

Could you briefly say what feedback you have received about the pavilion?

During the opening of the pavilion, the feedback was excellent; I presented the pavilion to a number of people, from Rem, through the research team of OMA, Ippolito, who did Monditalia in the Arsenale, Stephan, who did Elements in the central pavilion, as well as curators from other countries and journalists, and the feedback was more than good. Surprisingly for me, I expected that the theme and the book would resonate a lot towards the east; I anticipated it would work for Russia, Poland, Romania, etc., but to my surprise, the pavilion also received feedback from South American countries or countries like Korea, etc.

I would also like to return to other artifacts in the pavilion – we found that in the 1970s, 2-4% of the budget always went to art in public spaces. We found it interesting to use this rule and contact Tomáš Džadoň according to the same assignment to interact with our exhibition. He came up with the idea that we could work with a sign, and in the end, we settled on swapping Cecoslovacchia for Slovacchiaceco. This is a certain reminder that the pavilion is dedicated to Czechoslovakia for the first time, despite the fact that Czechoslovakia split into two independent states. A small detail is the two children's climbing structures that were prefabricated and manufactured in thousands of series, present in every kindergarten and school from 1965 to the early 1980s. We couldn’t find out who the author was. We had two pieces restored, transported them to Venice, where they serve, and subsequently they will be returned repaired to the children. To connect the book with the pavilion, so that the synergy between these two carriers of information is sufficient, we asked Alexej Kluykov, who is the author of the illustrations in the book, to write captions for the individual exhibited elements in the pavilion.

For us, the main question is what the role of the architect in society today is, when it is clear that the field for architecture is shrinking. Therefore, the subtitle of the book is 'atomized modernity' – there is a certain disintegration of grand ideas, large architectural firms, which are fragmenting into architectural studios with just a few people who do not have the stamina to have a bigger voice in society. Society fills this gap with quick solutions like catalog houses. The question is whether the profession of architect as such, as we know it, which we are aware of, is disappearing today in the position of designer on one hand or as an artist on the other, can survive and whether it even still exists, whether architects are perhaps dead and whether this is purely a peculiar nostalgia.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

1 comment

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

re.kniha,katalog

Zdeněk Skála

03.07.14 06:19

show all comments