Co-Lived, Co-Proposed, and Co-Created Eco-Systemic Responsiveness on the Ray 2 Wall

Source

Collaborative Collective, z.s.

Collaborative Collective, z.s.

Publisher

Tisková zpráva

30.01.2018 20:45

Tisková zpráva

30.01.2018 20:45

Czech Republic

Prague

Marie Davidová

|

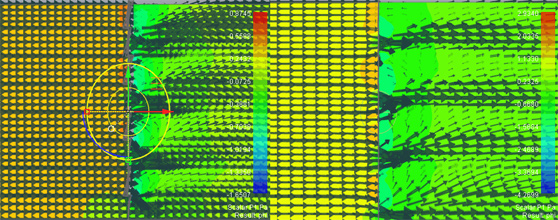

Image 1: Prototype of the responsive wall Ray 2 a) in rather dry April weather, when the wall opens for exchange between the exterior and semi-interior b) shortly after a light April rain, the system closed in order not to let the damp cold air pass through its boundary into the semi-interior. The photograph was taken after four years when the prototype was exposed to weather and biotic conditions near the forest. The prototype was inhabited by blue mold, algae, and lichens. These regulate the moisture of the wood and thus contribute to its warping. Notice also the organization of the algae habitation in the direction of the fibers of the material and thus its further interaction with its moisture. (photo: Davidová 2017)

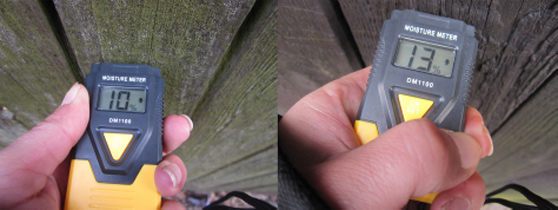

Current research on responsive 1) solid pine wood focuses on broader considerations of the material's interaction with the environment 2). Wood is one of the most significant renewable building materials, which has specific properties due to its biological nature. These include primarily its hygroscopicity, the material's interaction with relative humidity and temperature to achieve its equilibrium moisture. This research not only advances the current pioneering research by Michael Hensel and Achim Menges 3) in the field of responsive wood with laminates and plywood to solid wood in tangential cut, but also takes into account other biological species that can interact with it. Wood warps, expands, or contracts depending on the relative humidity, temperature, or other moisture-absorbing surrounding environments. The warping of the tangential cut generates the so-called "cup" across the direction of the fiber due to the different density of fibers on the left and right sides of the sample (Knight, 1961). This behavior can be utilized for organizing individual components into systems that respond to these stimuli for our benefit. Therefore, these systems operate using primary energy, meaning without the need for electrical energy. The responsive wall Ray designed by the author is to be applied in semi-interior spaces of human dwellings for ventilation in hot, dry weather and sealing in high relative humidity and low temperature. Such a system allows for ‘exchange across the system's boundaries’ (Addington, 2009; Addington & Schodek, 2005) between the outdoor and unconditioned indoor environments, which further moderates and is moderated by ‘climatic heterogeneity’ (Hensel, Hight, & Menges, 2009) of surrounding spaces.

|

Image 2: RhinoCFD Fluid Dynamics Simulation illustrating the exchange between the exterior and Semi-interior through the Ray wall; a) from the left: Situation in dry and hot weather when the wall is open; b) from the right: Situation with higher relative humidity and low temperature (simulation: Davidová 2017)

This means that these spaces further moderate and are moderated by the climatic diversity of surrounding spaces. This behavior occurs through an ever-evolving co-design 4) with its surrounding microclimatic and biotic environment. Unlike bioLogic, which works on synthetic biology for programmed hygromorphic transformations for human-computer interaction (Yao et al., 2015), this research deals with cooperation on co-living, co-design, and co-creation with other species and abiotic factors within the ecosystem 5). This also means that the research does not focus on industrial production based on synthetic biology, as in the example of Araya et al. (Araya, Zolotovsky, & Gidekel, 2012), but on generating a foundation that is further inhabited and lived by biotic organisms of their own volition based on local specifics.

The original tests for artificial algae cultivation on wood samples were by no means as successful as the prototypes exposed to real-life environments with their local natural inhabitants. From my initial measurements to confirm speculation, it appears that algae habitation on wood influences its moisture by two to four percent at an average relative humidity of the air (see Image 4). In high relative humidity after rain, I already measured a difference of up to ten percent on the Ray prototype (Image 5). Observed on the responsive wall Ray 2, algae spread along the wood fiber in its wettest areas. This seems to affect the warping of the material since the longest edge along the fiber has more algae growth, thus absorbing moisture. The warping on the Ray 2 prototype, which has a height of 30 cm at an equilateral triangle, differs by one centimeter at 15°C and 50% relative humidity, with greater deformation on panels with algae. This performance is mainly important at very high relative humidity, when algae prevent warping in the opposite direction. In hot and dry weather, on the other hand, it promotes ventilation.

|

Image 3: Samples of growth Apatococcu and Klebsormidia (from top to bottom) on: a) ash; b) acacia; and c) pine wood (from left to right) (photo: Davidová 2013)

|

Image 4: Fence with and without algae habitat measured with a hygrometer in Nové Město nad Metují (photo: Davidová 2013)

|

Image 5: Wood moisture on panels of prototype Ray 2 a) with algae and b) without algae; both at the same moment at 8°C and 66% relative humidity after a brief April rain (photo: Davidová 2017)

Therefore, these algae co-design, thus co-creating both the interaction of the prototype and environment and their appearance and distribution through their joint life in the system. While Carole Collet discusses co-design with fungi, where the organism designs a pattern through its inhabitation and this process is completed by humans baking the material and thus killing the fungus 6), this design research is 'non-anthropocentric' (Hensel, 2013), developing eco-systemic, responsive 'time-based design' (Sevaldson, 2004, 2017).

This means that this research does not aim to be fully pre-programmed. Non-living biological material from pine wood attracts living species that do not cause its decay, which distribute their habitation according to the interaction of its morphology with the weather. Sunlight, air humidity, and CO2 are absorbed and also released by these organisms the more they distribute themselves. This also causes an increase in their abundance. Decay-causing species are not very attracted to pine wood due to its highly acidic composition with a high amount of resin. Even so, the Ray 3 prototype has undergone a saline bath. This process removes sugar and amyl from the wood and thus does not attract decaying organisms that live off these nutrients. The Ray 3 prototype is relatively new and is still waiting for its habitat by biotic factors. Currently, its performance is primarily based on abiotic factors. For this reason, these walls evolve over time, serving not only human habitats. Altogether, such environments also create rich human personal and social situations for co-living and further co-creation through their psychological and climatic well-being (Davidová, 2016), understanding the being part of the biosphere 7). These processes of ‘performance-oriented design’ 8) thus still find themselves in feedback loops 9). This collective eco-systemic, responsive co-design, where the result is a continuous process, has led me to the ratification of a new field of design: Systemic Approach to Architectural Performance (Systemic Approach to Architectural Performance - SAAP).

Co-design has, in a sense, always been involved in the architectural process, as architects often co-create at least with their clients. Currently, architecture is slowly opening up to a somewhat broader transdisciplinarity and participation, focusing rather on biomimicry of systems than on the life of biological systems themselves. This article argues that this is not enough. We need to co-design in real-time the performance with the overall ecosystem with its biotic and abiotic factors.

Notes:

1) responsive predicts a mutual reaction and exchange with continuous adaptation on both sides of the applied balance‘ (Hookway & Perry, 2006) (translated by the author)

2) The environment is the physical and biological surroundings of an organism. The environment relates to non-living (abiotic factors) such as temperature, soil, atmosphere, and radiation, and also living (biotic) organisms like plants, microorganisms, and animals.‘ (Oxford University Press, 2004) (translated by the author)

3) The first contemporary prototype dealing with responsive wood was built by Asif Amir Khan at the AA School of Architecture in London under the guidance of Michael Hensel and Achim Menges in 2005 and was first published by them in the book Morpho-Ecologies in 2006 (Hensel & Menges, 2006).

4) The difference between co-design, i.e., co-creation and participation was explained by Sanders and Stappers, who only considered people. Co-design means rather the co-creation of stakeholders, while participation involves their engagement in the discussion about design with the possibility of considering their feedback (Sanders & Stappers, 2008).

5) The ecosystem has been described by Allen and Roberts as an ecological system within a system that includes the geophysical part (Allen & Roberts, 1993).

6) Public lecture by Carole Collet at the AA School of Applied Arts in Prague on 28.11.2016

7) The biosphere is 'an irregularly shaped envelope of the earth's atmosphere, water, and soil, which includes heights and depths in which living organisms exist. The biosphere is a closed and self-regulating system (see ecology), maintained by vast cycles of energy and materials - particularly carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, certain minerals and water. Basic recycling processes are photosynthesis, respiration, and nitrogen fixation by some bacteria. Disruption of basic ecological activities in the biosphere can lead to pollution.‘ (Lagasse & Columbia University, 2016) (translated by the author)

8) ‘Performance Oriented Design is a field of research dedicated to formulating inclusive design based on the interaction between various domains of factors that constitute the human environment.‘ (Hensel, 2015) (translated by the author)

9) ‘Feedback principle: The outcome of actions is always recorded and its successes or failures change future behavior.‘ (Skyttner, 2005)

References:

Addington, M. (2009). Contingent Behaviours. Architectural Design, 79(3), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.882

Addington, M., & Schodek, D. L. (2005). Smart Materials and Technologies in Architecture (1st ed.). Oxford: Architectural Press - Elsevier. Retrieved from https://bintian.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/smart-materials-new-technologies-for-the-architecture-design-professions.pdf

Allen, T. F. H., & Roberts, D. W. (1993). Foreword. In R. E. Ulanowicz (Ed.), Ecology, the Ascendent Perspective (pp. xi–xiii). New York: Columbia University Press.

Araya, S., Zolotovsky, E., & Gidekel, M. (2012). Living Architecture: Micro performances of bio fabrication. In H. Achten, J. Pavlicek, J. Hulin, & D. Matejovska (Eds.), Digital Physicality - Proceedings of the 30th eCAADe Conference - Volume 2 (pp. 437–448). Prague: Czech Technical University in Prague, Faculty of Architecture. Retrieved from http://papers.cumincad.org/data/works/att/ecaade2012_243.content.pdf

Davidová, M. (2016). Socio-Environmental Relations of Non-Discrete Spaces and Architectures: Systemic Approach to Performative Wood. In P. Jones (Ed.), Relating Systems Thinking and Design 2016 Symposium Proceedings (pp. 1–17). Toronto: Systemic Design Research Network. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B-0w-H8C5IDCWEtScUlNaVNrX1E/view

Hensel, M. (2013). Performance-Oriented Architecture: Rethinking Architectural Design and the Built Environment (1st ed.). West Sussex: John Willey & Sons Ltd.

Hensel, M. (2015). Performance-Oriented Design. Retrieved April 3, 2016, from http://www.performanceorienteddesign.net/

Hensel, M., Hight, C., & Menges, A. (2009). Space Reader: Heterogenous Space in Architecture. (M. Hensel, C. Hight, & A. Menges, Eds.). London: Wiley.

Hensel, M., & Menges, A. (2006). Morpho-Ecologies (1st ed.). London: AA Publications.

Hookway, B., & Perry, C. (2006). Responsive Systems|Appliance Architectures. Architectural Design, 76(5), 74–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.326

Knight, E. (1961). The Causes of Warp in Lumber Seasoning. Oregon.

Lagasse, P., & Columbia University. (2016). The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). New York: Columbia University Press.

Oxford University Press. (2004). World Encyclopedia (1st ed.). Published Online: Philip’s. https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780199546091.001.0001

Sanders, E. B.-N., & Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign, 4(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068

Sevaldson, B. (2004). Designing Time: A Laboratory for Time Based Design. In Future Ground (pp. 1–13). Melbourne: Monash University. Retrieved from http://www.futureground.monash.edu.au/.

Sevaldson, B. (2017). Systems Oriented Design. in preparation.

Skyttner, L. (2005). Basic Ideas of General Systems Theory. In General Systems Theory: : Problems, Perspectives, Practice (2nd ed., pp. 45–101). Singapore, Hackensack, London: WORLD SCIENTIFIC. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812384850_0002

Yao, L., Ou, J., Cheng, C.-Y., Steiner, H., Wang, W., Wang, G., & Ishii, H. (2015). bioLogic: Natto Cells as Nanoactuators for Shape Changing Interfaces. In B. Begole & J. Kim (Eds.), CHI ’15 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–10). Seoul: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702611

Marie Davidová, MArch.

Marie Davidová, MArch., Ph.D. Founding Member and Chair of Collaborative Collective, z.s.; Main Investigator of Systemic Approach to Architectural Performance Project at the Faculty of Art and Architecture at the Technical University of Liberec, Czechia, PhD Research Fellow at the Faculty of Art and Architecture at the Technical University of Liberec.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.