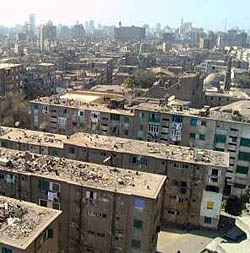

Many residents of Cairo must live on the roof

|

"In the summer, we eat, drink, and sleep out here," he says, pointing to the dusty roof. The monthly rent here is less than one American dollar. "It's better than living down there," he adds.

Some residents of Cairo's rooftops make use of makeshift toilets, plumbing, and even bathtubs. Others, however, have neither running water nor protection from the hot summer sun or winter rains. Some residents from lower social classes can rely on the water and toilet of their luckier neighbors from the apartments below, who are willing to offer them their hospitality.

"We don't have money to rent an apartment. Where else can we go?" says seventy-year-old Jazz Zidan Muhammad, who grew up, got married, and raised three children on the roof of one of the buildings.

Hundreds of thousands of Egyptians who flocked to Cairo during the economic boom of the 1970s cannot afford to rent an apartment. Instead, they build shacks on the rooftops of Cairo's buildings.

For their children, life on the rooftops is a reminder of the current economic development in Egypt's failure to improve the living standards of the poor. However, some argue that it's not a bad life. Rent is low, work is nearby, and perhaps most importantly, they are away from the hustle and crowds down below.

"Life on the roof is amazing because of the breeze and the sun," says Ibrahim Mahmoud, who raised three children 12 stories above the street. Mahmoud works as a telephone operator for a plastic manufacturing company. He came to Cairo 35 years ago. He decided to live on the roof because it is cheaper. He now pays four dollars a month. A comparable apartment is up to ten times more expensive.

According to experts, living on the roof is an acceptable solution to Cairo's housing problem. Almost half of the 14 million residents of Cairo live in areas where housing has not been planned or is not connected to sewage systems.

"Most investments, whether in production or services, go to Cairo. That's why people from agricultural areas head to this large urban center," says Abuzid Rajih from the National Research Center for Housing and Building.

The Egyptian economy grew at its fastest pace in two decades last year. This attracted more residents to Cairo, where 70,000 people live per square kilometer. "Cairo is growing at an uncontrollable pace," says Mahida al-Safty, a sociology professor at the American University in Cairo. "Informal housing can be a pragmatic solution," he adds.

Overcrowding, however, can lead to unrest. Protesters blocked Cairo's highways several times during the summer as they protested against the lack of drinking water. "The government talks about the issue of informal housing, but very little has actually been done," says Abuzid. For some, it is indeed better to live on the roof than to sleep on the street.

Nadia Awad Hisaniya moved into the wooden rooftop shelter ten years ago. She sleeps here because she has no job or other source of income. "When it's really hot, I sleep outside on the roof," she says.

On some larger rooftops, communities of families can create an environment that is better than that below them. Rooftop communities often communicate only among themselves.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

1 comment

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

žluté okno

Vích

13.10.07 09:55

show all comments