Exhibition: Artificial Perspective

Books on Perspective and Graphic Prints from the Castle Collections

Cabinet of the Governor's Palace of the Moravian Gallery in Brno

Moravian Square 1a, Brno

May 4 – August 5, 2007

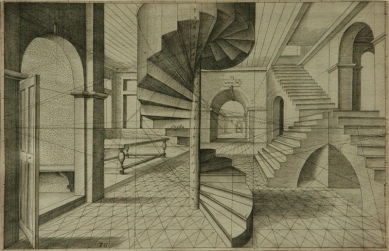

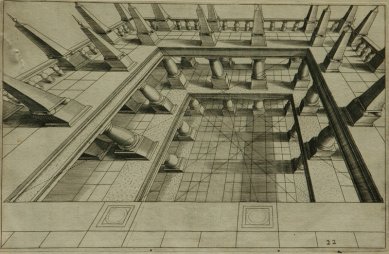

The exhibition Perspectiva artificialis, organized in collaboration with the National Heritage Institute in Brno, focuses on examples of Baroque perspective, architectural and geometric treatises, and graphic sheets. In the Cabinet of the Governor's Palace of MG and simultaneously in the exhibition hall at Rájec nad Svitavou castle, nearly 30 graphics and approximately the same number of books from the 17th and 18th centuries are presented, which represent independent artistic objects lying at the intersection of science, art, and literature.

In the history of art, we understand perspective as a tool for illusion serving to transfer real spatial relationships onto a pictorial surface using a system of lines or colors. The "discovery" of Renaissance perspective and the subsequent development of linear perspective construction were preceded by the development of ancient and later medieval optics and geometry. The term perspectiva artificialis (artificial or also artistic perspective) referred only to that kind of perspective related to the mathematical method of artistic representation. Ancient and medieval geometric optics, also referred to as "perspective" from the Latin perspicere – to see through something, primarily examined such phenomena as the path of a light ray – curvature, refraction, dispersion, reflection, etc., and dealt generally with questions of vision (Witelo, Euclid). Thus, it had seemingly little in common with today's notion of perspective. It was designated as perspectiva naturalis or communis (natural or common perspective). The new perspective system perspectiva artificialis can therefore be perceived to a certain extent as an application of optical theory to issues of artistic representation. Its authors were driven by the desire to create a structure that would have practical applications in artistic creation (Dubreuil, Vignola, Vredeman de Vries, etc.).

Renaissance perspectiva artificialis included a multitude of diverse methods, the most influential of which today is the schema of perspective projection first described by the Florentine architect and theorist Leon Battista Alberti in the Latin treatise De pictura (On Painting, 1435). During the following centuries, perspectiva artificialis became the subject of many theoretical treatises in various forms, which often took the form of lavishly prepared and richly illustrated volumes dedicated to noble patrons. From once esoteric teachings, particularly in the 17th century, which is sometimes called the "age of illusion" and simultaneously "the age of perspective," it became a broad academic discourse practiced and recommended to all architects, painters, etc. The treatises addressed issues related to representation (for example, transferring a given image onto irregularly shaped walls or ceilings – the so-called quadratura), contained mathematical aids for calculating or constructing three-dimensional images, and addressed other mathematical problems such as the calculation of mathematical infinity. They either acquainted readers with ancient patterns or conversely introduced new theories and their pictorial demonstrations.

To this, there was an expansion of various special and eccentric variants – anamorphoses – utilizing the absurd aspects of perspective construction. Special types of perspectives from the 17th century worked with the conventions of linear perspective to achieve various ingenious effects. However, the origin of these "perspective curiosities" dates back to the fifteenth century.

Books on perspective became an indispensable part of the Baroque "image of the world," for whose scaled-down model we can metaphorically consider the representative library of an educated aristocrat or architect. One such library was assembled by Olomouc Bishop Karel II of Liechtenstein – Castlekorna (1637–1695), a church aristocrat and patron of the arts, who was educated in building matters as the builder of his Kroměříž residence. The library had a representative purpose – it included works of classical architectural theory: Vitruvius, Vignola, Vincenzo Scamozzi – but also a practical one – fortification manuals, books on building. Among significant works dealing exclusively with perspective, the inventory lists influential treatises by Samuel Marolois and Vredeman de Vries.

Another example could be the so-called Grimm Collection, which was acquired at the end of the 18th century by Prince and Count Karl Josef of Salm-Reifferscheidt (1750–1838) for his library at the Rájec nad Svitavou castle. Here we encounter the collecting result of the professionally motivated interest of an 18th-century engineer, builder, and architect, František Antonín Grimm from Brno (1710―1784). The collection, which in its significance, i.e., size and focus, exceeds the boundaries of Moravian and Central European space, consists of a convolute of architectural drawings, sketchbooks, manuscripts, and books on architecture, building, mathematics, perspective, and geometry.

Treatises, although they could contain various technical data, schematic drawings, etc., were evidently not primarily intended for builders, and their goal was not only to provide practical instructions. We can much more understand them as a certain new type of literature. They became part of the general cultural discourse, served education, entertainment, reflected and shaped contemporary conventions, and served as a platform for organizing views on taste. They facilitated the emancipation of the architect as an independent artist and author, and also for dilettantes among the aristocrats. This is also why theoretical treatises and textbooks on geometry or perspective have their place in castle libraries.

A characteristic example of practical knowledge of perspective usage is ideal architectural prospects and vedutas, which are referred to in contemporary vocabulary as Prospect, Perspectivischer Aufzug, Szenographia, Veue et perspective, Plan perspectif, etc. At the beginning of the 18th century, architects appeared who presented various designs in large-format graphic sheets to showcase their skills to attract potential clients (Paul Decker, Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach). Architectural drawings utilize elements of scenography, paying attention to "painterly" means such as shading and lighting, staging of the building.

It was the "archaeological and architectural vedutas," whose characteristic representative is the graphic sheets of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778), that revived theoretical interest in perspective in the 18th century, as they adhered more to the rules of perspective representation than other types of landscape painting.

The reach of perspective discourse was not limited to manuals and scholarly treatises, but included ideas hidden in the symbolic language of personifications and emblems. Perspective is also not and was not merely a system of mathematical rules or a practical method but also a source of rich iconography and a rhetorical formula. One-point linear perspective, for example, is associated with the construction of the Cartesian concept of "I", the deceptive perspective of Baroque architecture is often perceived as equivalent to illusionism and tenebrism in painting, but also to the Baroque epigram and poetic wit.

Poets as well as creators of optical tricks found a common theme in anamorphic images, perspective boxes, but also mirrors, lenses, telescopes, and optical prisms. Their work thus extends to remote areas, such as scenography or the design of garden landscapes. Optical and perspective tricks, including the associated aids and inventions, found their echo in poetry, as in Shakespeare, who in his 24th sonnet referred to perspective as "the most perfect painting art".

Moravian Square 1a, Brno

May 4 – August 5, 2007

The exhibition Perspectiva artificialis, organized in collaboration with the National Heritage Institute in Brno, focuses on examples of Baroque perspective, architectural and geometric treatises, and graphic sheets. In the Cabinet of the Governor's Palace of MG and simultaneously in the exhibition hall at Rájec nad Svitavou castle, nearly 30 graphics and approximately the same number of books from the 17th and 18th centuries are presented, which represent independent artistic objects lying at the intersection of science, art, and literature.

In the history of art, we understand perspective as a tool for illusion serving to transfer real spatial relationships onto a pictorial surface using a system of lines or colors. The "discovery" of Renaissance perspective and the subsequent development of linear perspective construction were preceded by the development of ancient and later medieval optics and geometry. The term perspectiva artificialis (artificial or also artistic perspective) referred only to that kind of perspective related to the mathematical method of artistic representation. Ancient and medieval geometric optics, also referred to as "perspective" from the Latin perspicere – to see through something, primarily examined such phenomena as the path of a light ray – curvature, refraction, dispersion, reflection, etc., and dealt generally with questions of vision (Witelo, Euclid). Thus, it had seemingly little in common with today's notion of perspective. It was designated as perspectiva naturalis or communis (natural or common perspective). The new perspective system perspectiva artificialis can therefore be perceived to a certain extent as an application of optical theory to issues of artistic representation. Its authors were driven by the desire to create a structure that would have practical applications in artistic creation (Dubreuil, Vignola, Vredeman de Vries, etc.).

Renaissance perspectiva artificialis included a multitude of diverse methods, the most influential of which today is the schema of perspective projection first described by the Florentine architect and theorist Leon Battista Alberti in the Latin treatise De pictura (On Painting, 1435). During the following centuries, perspectiva artificialis became the subject of many theoretical treatises in various forms, which often took the form of lavishly prepared and richly illustrated volumes dedicated to noble patrons. From once esoteric teachings, particularly in the 17th century, which is sometimes called the "age of illusion" and simultaneously "the age of perspective," it became a broad academic discourse practiced and recommended to all architects, painters, etc. The treatises addressed issues related to representation (for example, transferring a given image onto irregularly shaped walls or ceilings – the so-called quadratura), contained mathematical aids for calculating or constructing three-dimensional images, and addressed other mathematical problems such as the calculation of mathematical infinity. They either acquainted readers with ancient patterns or conversely introduced new theories and their pictorial demonstrations.

To this, there was an expansion of various special and eccentric variants – anamorphoses – utilizing the absurd aspects of perspective construction. Special types of perspectives from the 17th century worked with the conventions of linear perspective to achieve various ingenious effects. However, the origin of these "perspective curiosities" dates back to the fifteenth century.

Books on perspective became an indispensable part of the Baroque "image of the world," for whose scaled-down model we can metaphorically consider the representative library of an educated aristocrat or architect. One such library was assembled by Olomouc Bishop Karel II of Liechtenstein – Castlekorna (1637–1695), a church aristocrat and patron of the arts, who was educated in building matters as the builder of his Kroměříž residence. The library had a representative purpose – it included works of classical architectural theory: Vitruvius, Vignola, Vincenzo Scamozzi – but also a practical one – fortification manuals, books on building. Among significant works dealing exclusively with perspective, the inventory lists influential treatises by Samuel Marolois and Vredeman de Vries.

Another example could be the so-called Grimm Collection, which was acquired at the end of the 18th century by Prince and Count Karl Josef of Salm-Reifferscheidt (1750–1838) for his library at the Rájec nad Svitavou castle. Here we encounter the collecting result of the professionally motivated interest of an 18th-century engineer, builder, and architect, František Antonín Grimm from Brno (1710―1784). The collection, which in its significance, i.e., size and focus, exceeds the boundaries of Moravian and Central European space, consists of a convolute of architectural drawings, sketchbooks, manuscripts, and books on architecture, building, mathematics, perspective, and geometry.

Treatises, although they could contain various technical data, schematic drawings, etc., were evidently not primarily intended for builders, and their goal was not only to provide practical instructions. We can much more understand them as a certain new type of literature. They became part of the general cultural discourse, served education, entertainment, reflected and shaped contemporary conventions, and served as a platform for organizing views on taste. They facilitated the emancipation of the architect as an independent artist and author, and also for dilettantes among the aristocrats. This is also why theoretical treatises and textbooks on geometry or perspective have their place in castle libraries.

A characteristic example of practical knowledge of perspective usage is ideal architectural prospects and vedutas, which are referred to in contemporary vocabulary as Prospect, Perspectivischer Aufzug, Szenographia, Veue et perspective, Plan perspectif, etc. At the beginning of the 18th century, architects appeared who presented various designs in large-format graphic sheets to showcase their skills to attract potential clients (Paul Decker, Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach). Architectural drawings utilize elements of scenography, paying attention to "painterly" means such as shading and lighting, staging of the building.

It was the "archaeological and architectural vedutas," whose characteristic representative is the graphic sheets of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778), that revived theoretical interest in perspective in the 18th century, as they adhered more to the rules of perspective representation than other types of landscape painting.

The reach of perspective discourse was not limited to manuals and scholarly treatises, but included ideas hidden in the symbolic language of personifications and emblems. Perspective is also not and was not merely a system of mathematical rules or a practical method but also a source of rich iconography and a rhetorical formula. One-point linear perspective, for example, is associated with the construction of the Cartesian concept of "I", the deceptive perspective of Baroque architecture is often perceived as equivalent to illusionism and tenebrism in painting, but also to the Baroque epigram and poetic wit.

Poets as well as creators of optical tricks found a common theme in anamorphic images, perspective boxes, but also mirrors, lenses, telescopes, and optical prisms. Their work thus extends to remote areas, such as scenography or the design of garden landscapes. Optical and perspective tricks, including the associated aids and inventions, found their echo in poetry, as in Shakespeare, who in his 24th sonnet referred to perspective as "the most perfect painting art".

Petr Ingerle

EXHIBITION ORGANIZERS

Moravian Gallery in Brno

National Heritage Institute in Brno

State Castle Rájec nad Svitavou

EXHIBITION CURATORS

Petr Ingerle, Lenka Kalábová

GRAPHIC DESIGN OF PRINT MATERIALS

Jiří Maška

PRODUCTION

Miroslava Pluháčková

PROMOTION

Hana Doležalová, Simona Juračková, Eva Maňasová

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment