<title>The Venice Biennale 2018 - A Reflection by Ondřej Hojda on the Exhibition</title>The Venice Biennale 2018 - A Reflection by Ondřej Hojda on the Exhibition

16th International Architecture Exhibition in Venice: Free Space and Freespace

The International Architecture Exhibition in Venice, organized by the Venice Biennale and briefly called the Biennale of Architecture, is taking place for the sixteenth time this year. Once again, the curators selected were architects, specifically female architects – the Irish duo Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara, who have been collaborating for forty years under the name Grafton architects. They were responsible for the extensive main exhibition in the large pavilion in the Giardini gardens and the areas of corderie and parts of artiglierií in the Arsenale. National pavilions are also expected to respond to the designated theme, but usually, each country does what it wants anyway. However, this year, the response worked more than ever, and a diverse yet interconnected whole can be seen.

The credit for this obviously goes to the theme, which is broad enough to inspire everyone: Freespace – free, unbounded space. The Venice Biennale, in a sympathetically anachronistic spirit, compels its curators to write their own “manifesto”: According to Farrell and McNamara, freespace means “generosity and a sense of humanity at the core of architecture” and “a focus on the quality of space itself.” “Freespace” can be “an added, unexpected gift,” something that architects should be able to extract even from the most modest project, even if it may be a seemingly trivial detail. The authors illustrate this with specific examples: they mention Jørn Utzon’s concrete, tiled bench at his house in Lis on Mallorca, the entrance to the Milan house on Via Quadronno 24 by Angelo Mangiarotti, the free space given to the public by architect Lina Bo Bardi under her piloti-built museum in São Paulo, and the stone bench of the Florentine Palazzo Medici, which transforms the adjacent space into its own unique interior. It can thus be said that such freespace is perhaps what still distinguishes architecture from mere building.

However, one might argue that “space itself” offers an infinite number of meanings, and neither “freedom” nor “liberty” specifies it accurately. Considering space as a fundamental element of architecture is not at all as self-evident as it may seem today: it began with modernists at the beginning of the 20th century, heavily inspired by art historians. As long as the concept functions as an understandable medium both within the profession and for communication with the public, it is not much of a problem. The multitude of meanings of space is further transformed in the authors’ manifesto into a programmatic openness toward various approaches, and freespace literally invites the filling of meanings. They explicitly mention the socio-political one (which dominated the previous biennale curated by Alejandro Aravena); that which we could call “phenomenological” (“light, air, and materials,” significantly applied in biennale 2010), as well as the freedom to creatively handle history. It can thus be said that this year's exhibition encompasses all the themes of previous biennales from this decade. Conversely absent are the ostentation and polished self-centeredness from the times of the economic bubble, which concluded with the Venice exhibitions ten years ago with the exhibition Beyond Building (2008). For those who regularly attend the Venice Architecture Biennale, the themes and many participants will naturally be familiar. Nevertheless, it cannot be said that it is a weak, unimpressive, or opinionless exhibition.

Main Trends: Return to Houses, Gender Balance, Working with Place

Those who found the last biennale a bit too information-packed might find it a relief this year, as might those who succumbed to the feeling of despair and impotence of architecture in the face of more powerful forces shaping our world. It can be said that architecture as building houses is back this year, and buildings, models, and specific projects are the main subject and means of communication. Though it is a return to safe ground for architects, it does not feel like an escape. The lessons and questions posed by the previous two conceptually defined biennales are not forgotten and continue to be engaged with. Although the authors addressed participants from all over the world, there is a palpable distinct taste and a great degree of control over the entire exhibition space. Ultimately, the whole is remarkably balanced and convincingly managed despite its scale.

From the feedback thus far, this year's biennale seems to be unifying rather than provoking disputes. One fact, which compelled me to clarify right in the second sentence of this text, contains controversial potential: for the first time this year, the curators of the architectural biennale are entirely women. The fact that the architectural profession is still an extreme domain of men is not directly addressed by the Irish duo of architects, who choose a calmer path through the convincing results of their own work; however, their selection of exhibitors is notably gender-balanced within the possibilities. Attention to the issue was sought during the opening on May 25 through a demonstration, organized by architects Odile Decq, Farhid Moussavi, and Caroline James directly in the biennale grounds. This protest also aimed outward, not against the exhibition; it was even meant as a tribute to the curators. Decq is, after all, one of the exhibitors herself.

In accordance with the principles of their freespace, the authors left the entrance halls open in both the Giardini and Arsenal. The change is noticeable in the first area only after a moment, when we notice the unusual tiles (from Granby Workshop in Liverpool, established by the young architectural collective Assemble). In the Arsenale, one must part a curtain made of suspended ropes, reminiscent of the history of the site – the three-hundred-meter corderie, originally a rope manufacturing factory. The Irish architects found a great conclusion for their declared approach when preparing the exhibition spaces: at the back of the large pavilion in the Giardini, they revealed a long-bricked-up window in the form of two intersecting circles designed by Carlo Scarpa. Also in the interior of the Arsenale, which almost completely lacks natural light, a light at the end moves along the entire three hundred meters of corderie, refracting off freely placed columns by Valerio Olgiati. However, it takes a long time for the viewer to reach there, and it must be admitted that the decision to leave the entire central axis open and to assign uniformly small spaces to the exhibitors on the sides leads, with more than a hundred exhibitors, to a certain monotony.

Schools, History, Matadors, and Discoveries

The curators defined their broad mandate by separating narrower special sections, which follow immediately after the entrance hall in both main exhibition spaces. In the Arsenale, selected architects – including Ticino matadors, Mario Botta and Aurelio Galfetti – express their views on the issue of education in their own ways. It is worth pausing here at the projects of the Indian school from Case Design (A School in the Making), or the impressive large model of a school in Tokyo from Tezuka architects, similar to the school in Líbeznice by the Czech studio projektil. In the Giardini, there is the exhibition Close Encounter, where contemporary Irish studios were tasked with confronting specific buildings, mostly from the twentieth century. The results are of course varied and show that even good building architects are not always convincing installation architects.

Big names like Alvaro Siza and Rafael Moneo will draw attention among the participants (and their contributions are hardly among the most interesting), so lesser-known authors deserve to be highlighted here. It is worth literally putting one’s head into the installation Field by the Portuguese studio Aires Mateus with dreamlike landscapes inside, stopping at the presentation of vertical sections by the Spanish studio Paredes Pedrosa, the generous residential building Tila in Helsinki by the Finnish studio Talli, or the Gowan Court building by the British studio 6a architects, presented through the film Trees Down Here by experimental filmmaker Ben Rivers (all in the Arsenale). Without feeling out of place, one can enjoy the large, meticulously crafted models of buildings by Peter Zumthor (Giardini).

This year's biennale is close to the one from 2012, prepared by David Chipperfield under the name Common Ground. Chipperfield himself participates in the main exhibition with an installation dominated by historic graphics, where architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel depicted the view from the first floor of Berlin's Altes Museum (Beyond Purpose, Giardini). Chipperfield has been working on the Museum Island in Berlin for a long time and seeks to embody the principle of this original openness in the recently completed entry object Joseph-Simon Galerie. The Luxembourg pavilion (Arsenale) is certainly worth attention, as it fills the room with giant models of realized and unrealized large-scale buildings and is literally named Architecture of the Common Ground.

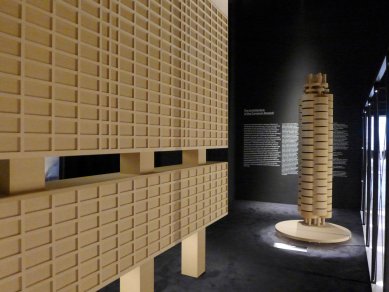

The first Venice Architecture Exhibition in 1980 was called The Presence of the Past, and history has naturally always been present at the biennale; however, this year it seems to be even more than usual. The installation Freespace in Place presents four unrealized projects for Venice by world-famous architects – Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Carlo Scarpa, and – perhaps the least known – a park proposal by Isamu Noguchi. The exhibition Freestanding chooses three entry halls from the work of Swedish modern classic Sigurd Lewerentz; Cino Zucchi prepared a precisely executed homage to his favorite, Milanese architect Luigi Caccia Dominioni (1913–2016), who recently passed away at nearly 103 years old. The installation includes models of publicly accessible interiors of Dominioni’s buildings in Milan as well as translucent models of the interiors. London's Victoria and Albert Museum brought an interesting exhibition on the legendary but recently demolished complex Robin Hood Gardens by Alison and Peter Smithson, including a three-story segment of the façade. The Russian pavilion (Station Russia, Giardini) deals with the history of railways in this country. Flemish architects de vylder vinck taillieu, who co-created the excellent Belgian pavilion in 2016, dedicate an entire room to their project of rehabilitating a building in a psychiatric hospital near Ghent (Unless ever people, Giardini). This project is special compared to other restorations of historical houses as it lacks a clear brief and fixes the building in its partially ruined state, thus presenting a theme of memory as well as openness and freedom. Swedish Skälsö arkitekter present their project of converting bunkers – until recently used by the army (Bungenäs, Arsenale). The theme could resonate in the Czech Republic as well, where even minimal intervention into a “řopík” meets with resistance. British Caruso and St John The Facade is the Window to the Soul of Architecture also relate their installation to their modern historical templates.

Empty Pavilions, Free and Public Space

Adam Caruso and Colin St John were also the commissioners of the British pavilion (Island, Giardini), but already upon entry, there is a suspicion that they did not manage to devote as much attention to it as to their own exhibition. The theme of freespace was taken literally here: the pavilion is completely empty (it is supposed to be filled with activities) but a temporary terrace has been built over the roof. As a one-liner, however, it fails in the details, as noted by The Guardian. The colorful motif on the floor of the roof terrace reveals the authors to those who have already sat on their bench in the main pavilion – the terrace offers an interesting view that disappears when we sit in chairs. Moreover, this year the Hungarians also built a very similar roof terrace above their pavilion.

As a challenge for direct action, the theme of freespace has been embraced by several national pavilions:

The Spaniards opened to visitors a normally inaccessible small garden behind their pavilion, while the Scandinavian pavilion designed by Sverre Fehn is inhabited only by inflatable creature-like objects that expand or contract due to heat sensors depending on the number of visitors (Another Generosity). This installation inadvertently references another of Fehn’s unrealized and atypical projects for an inflatable pavilion at the international exhibition in Osaka (1970). The Australian pavilion (Repair, Giardini) is filled with grasses from Queensland, while the Argentine pavilion (Vértigo horizontal, Arsenale) simulates the experience of the pampas with clouds racing above it. The Belgian pavilion is essentially empty as well (Eurotopia, Giardini); Bahrain only delineated its space in the form of a mosque and allows prayer to sound here (Friday Prayer, Arsenale).

Others addressed the theme more classically and identified freespace with the theme of public space: already mentioned Hungary (Liberty Bridge, Giardini) and Luxembourg (Arsenale). Others connected it with a related theme of public buildings – buildings that emerged from public competitions (Muros de ar [Walls from the Air], Brazil pavilion, Giardini), public libraries (Building Knowledge, Finland pavilion, Giardini), universities (Schools of Athens, Greece pavilion, Giardini), or unrealized projects for conflictual public spaces at the Wailing Wall (In Statu Quo: Structures of Negotiation, Israel pavilion, Giardini). The Estonian pavilion (via Garibaldi, Castello), prepared by a trio of young architects Laura Linsi, Roland Reemaa, and Tadeáš Říha in a deconsecrated church, is also worth attention. The conceptual installation is based on the idea of “weak monument,” referring to the work of the last of them.

Focus: Poland, Switzerland, Czech Republic

An evergreen in all biennale reviews is the exhibition's overwhelming scale, which is challenging for visitors. However, the problem seems rather to be the adaptation of exhibitors to this format. Especially in the national pavilions, one still encounters exhibitions that are well and diligently prepared but set for concentration and time, ideally requiring a whole afternoon. This includes the ambitious American pavilion this year, examining various forms of civic engagement (Dimensions of Citizenship, Giardini), which somewhat presumptively assumes familiarity with the internal tensions of the country. South Korea cannot rely on that, having traditionally prepared a very high-quality pavilion dedicated this year to the sixties (Spectres of State Avant-Garde, Giardini). Thus, we also encounter installations that may not catch the attention of most viewers at first glance, but their quality – or absence thereof – becomes apparent upon closer examination. Among the better group is the content-wise very interesting installation and accompanying publication Amplifying Nature (Poland pavilion, Giardini): contemporary authors Małgorzata Kuciewicz and Simone de Iacobis from the studio CENTRALA approach the perspective of the Anthropocene, a hypothesis that is being increasingly accepted, which posits that human alteration of the Earth’s surface can be considered a separate geological epoch. This is of course a highly architectural theme, as transforming the Earth’s surface is ultimately the main content of architecture. Through more or less experimental architectural projects, they explore how architecture can sustain and amplify natural processes, the cycle of natural light, and primarily water, which also dominates the installation. Interestingly, in addition to their own works, the authors brought into play older Polish modernists of the 60s and 70s (Oskar and Zofia Hansen, Jacek Damięcki) and, for example, demonstrated through the well-thought-out project of the Warszawianka sports complex on the outskirts of Warsaw that modernism was not insensate to these issues contrary to widely held beliefs.

Within the exhibition, however, simple and easily understandable solutions work best. The Swiss know this, and their pavilion also received the Golden Lion for the best national representation. The installation Svizzera 240 plays with the standardization of contemporary residential construction (the name derives from the usually required ceiling height). The sterile spaces of unfurnished interiors feel like a tour of a newly constructed residential building: the same doorknobs, various sockets, white doors. But soon we realize something is amiss: the scale changes. This naturally creates a disorienting impression, leading to an experience of space that is not transferable via photograph: “a place where real estate agents probably go to die,” as Oliver Wainwright wrote.

This year, attention is also drawn to UNES-CO, a project by Kateřina Šedá in the Czech, or rather Czech-Slovak pavilion (Giardini). Having recently received the title of “Architect of the Year,” the selection of this artist confirms a possible shift in the still relatively conservative perception in the Czech Republic of the boundaries of who can actively express themselves about architecture. UNES-CO is a fictional company that Šedá invented in an effort to combat the displacement of everyday life from tourist-frequented locations, often under the protection of the international organization UNESCO. The name serves as a pun in different ways in both Czech and English. Hired individuals will perform their daily activities on the streets of Český Krumlov during the summer months. The thoroughness and patience of Kateřina Šedá give hope that the “ordinary life” broadcast live to Venice, which may seem dangerously close to a reality show based on mere description, will reinforce human and community relationships as the author has successfully done in her previous projects. Thanks to some of them (Bedřichovice nad Temží, 2011–2015), she has already tested her approach abroad, and visitor responses to the Venice pavilion have so far been positive.

The credit for this obviously goes to the theme, which is broad enough to inspire everyone: Freespace – free, unbounded space. The Venice Biennale, in a sympathetically anachronistic spirit, compels its curators to write their own “manifesto”: According to Farrell and McNamara, freespace means “generosity and a sense of humanity at the core of architecture” and “a focus on the quality of space itself.” “Freespace” can be “an added, unexpected gift,” something that architects should be able to extract even from the most modest project, even if it may be a seemingly trivial detail. The authors illustrate this with specific examples: they mention Jørn Utzon’s concrete, tiled bench at his house in Lis on Mallorca, the entrance to the Milan house on Via Quadronno 24 by Angelo Mangiarotti, the free space given to the public by architect Lina Bo Bardi under her piloti-built museum in São Paulo, and the stone bench of the Florentine Palazzo Medici, which transforms the adjacent space into its own unique interior. It can thus be said that such freespace is perhaps what still distinguishes architecture from mere building.

However, one might argue that “space itself” offers an infinite number of meanings, and neither “freedom” nor “liberty” specifies it accurately. Considering space as a fundamental element of architecture is not at all as self-evident as it may seem today: it began with modernists at the beginning of the 20th century, heavily inspired by art historians. As long as the concept functions as an understandable medium both within the profession and for communication with the public, it is not much of a problem. The multitude of meanings of space is further transformed in the authors’ manifesto into a programmatic openness toward various approaches, and freespace literally invites the filling of meanings. They explicitly mention the socio-political one (which dominated the previous biennale curated by Alejandro Aravena); that which we could call “phenomenological” (“light, air, and materials,” significantly applied in biennale 2010), as well as the freedom to creatively handle history. It can thus be said that this year's exhibition encompasses all the themes of previous biennales from this decade. Conversely absent are the ostentation and polished self-centeredness from the times of the economic bubble, which concluded with the Venice exhibitions ten years ago with the exhibition Beyond Building (2008). For those who regularly attend the Venice Architecture Biennale, the themes and many participants will naturally be familiar. Nevertheless, it cannot be said that it is a weak, unimpressive, or opinionless exhibition.

Main Trends: Return to Houses, Gender Balance, Working with Place

Those who found the last biennale a bit too information-packed might find it a relief this year, as might those who succumbed to the feeling of despair and impotence of architecture in the face of more powerful forces shaping our world. It can be said that architecture as building houses is back this year, and buildings, models, and specific projects are the main subject and means of communication. Though it is a return to safe ground for architects, it does not feel like an escape. The lessons and questions posed by the previous two conceptually defined biennales are not forgotten and continue to be engaged with. Although the authors addressed participants from all over the world, there is a palpable distinct taste and a great degree of control over the entire exhibition space. Ultimately, the whole is remarkably balanced and convincingly managed despite its scale.

From the feedback thus far, this year's biennale seems to be unifying rather than provoking disputes. One fact, which compelled me to clarify right in the second sentence of this text, contains controversial potential: for the first time this year, the curators of the architectural biennale are entirely women. The fact that the architectural profession is still an extreme domain of men is not directly addressed by the Irish duo of architects, who choose a calmer path through the convincing results of their own work; however, their selection of exhibitors is notably gender-balanced within the possibilities. Attention to the issue was sought during the opening on May 25 through a demonstration, organized by architects Odile Decq, Farhid Moussavi, and Caroline James directly in the biennale grounds. This protest also aimed outward, not against the exhibition; it was even meant as a tribute to the curators. Decq is, after all, one of the exhibitors herself.

In accordance with the principles of their freespace, the authors left the entrance halls open in both the Giardini and Arsenal. The change is noticeable in the first area only after a moment, when we notice the unusual tiles (from Granby Workshop in Liverpool, established by the young architectural collective Assemble). In the Arsenale, one must part a curtain made of suspended ropes, reminiscent of the history of the site – the three-hundred-meter corderie, originally a rope manufacturing factory. The Irish architects found a great conclusion for their declared approach when preparing the exhibition spaces: at the back of the large pavilion in the Giardini, they revealed a long-bricked-up window in the form of two intersecting circles designed by Carlo Scarpa. Also in the interior of the Arsenale, which almost completely lacks natural light, a light at the end moves along the entire three hundred meters of corderie, refracting off freely placed columns by Valerio Olgiati. However, it takes a long time for the viewer to reach there, and it must be admitted that the decision to leave the entire central axis open and to assign uniformly small spaces to the exhibitors on the sides leads, with more than a hundred exhibitors, to a certain monotony.

Schools, History, Matadors, and Discoveries

The curators defined their broad mandate by separating narrower special sections, which follow immediately after the entrance hall in both main exhibition spaces. In the Arsenale, selected architects – including Ticino matadors, Mario Botta and Aurelio Galfetti – express their views on the issue of education in their own ways. It is worth pausing here at the projects of the Indian school from Case Design (A School in the Making), or the impressive large model of a school in Tokyo from Tezuka architects, similar to the school in Líbeznice by the Czech studio projektil. In the Giardini, there is the exhibition Close Encounter, where contemporary Irish studios were tasked with confronting specific buildings, mostly from the twentieth century. The results are of course varied and show that even good building architects are not always convincing installation architects.

Big names like Alvaro Siza and Rafael Moneo will draw attention among the participants (and their contributions are hardly among the most interesting), so lesser-known authors deserve to be highlighted here. It is worth literally putting one’s head into the installation Field by the Portuguese studio Aires Mateus with dreamlike landscapes inside, stopping at the presentation of vertical sections by the Spanish studio Paredes Pedrosa, the generous residential building Tila in Helsinki by the Finnish studio Talli, or the Gowan Court building by the British studio 6a architects, presented through the film Trees Down Here by experimental filmmaker Ben Rivers (all in the Arsenale). Without feeling out of place, one can enjoy the large, meticulously crafted models of buildings by Peter Zumthor (Giardini).

This year's biennale is close to the one from 2012, prepared by David Chipperfield under the name Common Ground. Chipperfield himself participates in the main exhibition with an installation dominated by historic graphics, where architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel depicted the view from the first floor of Berlin's Altes Museum (Beyond Purpose, Giardini). Chipperfield has been working on the Museum Island in Berlin for a long time and seeks to embody the principle of this original openness in the recently completed entry object Joseph-Simon Galerie. The Luxembourg pavilion (Arsenale) is certainly worth attention, as it fills the room with giant models of realized and unrealized large-scale buildings and is literally named Architecture of the Common Ground.

The first Venice Architecture Exhibition in 1980 was called The Presence of the Past, and history has naturally always been present at the biennale; however, this year it seems to be even more than usual. The installation Freespace in Place presents four unrealized projects for Venice by world-famous architects – Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Carlo Scarpa, and – perhaps the least known – a park proposal by Isamu Noguchi. The exhibition Freestanding chooses three entry halls from the work of Swedish modern classic Sigurd Lewerentz; Cino Zucchi prepared a precisely executed homage to his favorite, Milanese architect Luigi Caccia Dominioni (1913–2016), who recently passed away at nearly 103 years old. The installation includes models of publicly accessible interiors of Dominioni’s buildings in Milan as well as translucent models of the interiors. London's Victoria and Albert Museum brought an interesting exhibition on the legendary but recently demolished complex Robin Hood Gardens by Alison and Peter Smithson, including a three-story segment of the façade. The Russian pavilion (Station Russia, Giardini) deals with the history of railways in this country. Flemish architects de vylder vinck taillieu, who co-created the excellent Belgian pavilion in 2016, dedicate an entire room to their project of rehabilitating a building in a psychiatric hospital near Ghent (Unless ever people, Giardini). This project is special compared to other restorations of historical houses as it lacks a clear brief and fixes the building in its partially ruined state, thus presenting a theme of memory as well as openness and freedom. Swedish Skälsö arkitekter present their project of converting bunkers – until recently used by the army (Bungenäs, Arsenale). The theme could resonate in the Czech Republic as well, where even minimal intervention into a “řopík” meets with resistance. British Caruso and St John The Facade is the Window to the Soul of Architecture also relate their installation to their modern historical templates.

Empty Pavilions, Free and Public Space

Adam Caruso and Colin St John were also the commissioners of the British pavilion (Island, Giardini), but already upon entry, there is a suspicion that they did not manage to devote as much attention to it as to their own exhibition. The theme of freespace was taken literally here: the pavilion is completely empty (it is supposed to be filled with activities) but a temporary terrace has been built over the roof. As a one-liner, however, it fails in the details, as noted by The Guardian. The colorful motif on the floor of the roof terrace reveals the authors to those who have already sat on their bench in the main pavilion – the terrace offers an interesting view that disappears when we sit in chairs. Moreover, this year the Hungarians also built a very similar roof terrace above their pavilion.

As a challenge for direct action, the theme of freespace has been embraced by several national pavilions:

The Spaniards opened to visitors a normally inaccessible small garden behind their pavilion, while the Scandinavian pavilion designed by Sverre Fehn is inhabited only by inflatable creature-like objects that expand or contract due to heat sensors depending on the number of visitors (Another Generosity). This installation inadvertently references another of Fehn’s unrealized and atypical projects for an inflatable pavilion at the international exhibition in Osaka (1970). The Australian pavilion (Repair, Giardini) is filled with grasses from Queensland, while the Argentine pavilion (Vértigo horizontal, Arsenale) simulates the experience of the pampas with clouds racing above it. The Belgian pavilion is essentially empty as well (Eurotopia, Giardini); Bahrain only delineated its space in the form of a mosque and allows prayer to sound here (Friday Prayer, Arsenale).

Others addressed the theme more classically and identified freespace with the theme of public space: already mentioned Hungary (Liberty Bridge, Giardini) and Luxembourg (Arsenale). Others connected it with a related theme of public buildings – buildings that emerged from public competitions (Muros de ar [Walls from the Air], Brazil pavilion, Giardini), public libraries (Building Knowledge, Finland pavilion, Giardini), universities (Schools of Athens, Greece pavilion, Giardini), or unrealized projects for conflictual public spaces at the Wailing Wall (In Statu Quo: Structures of Negotiation, Israel pavilion, Giardini). The Estonian pavilion (via Garibaldi, Castello), prepared by a trio of young architects Laura Linsi, Roland Reemaa, and Tadeáš Říha in a deconsecrated church, is also worth attention. The conceptual installation is based on the idea of “weak monument,” referring to the work of the last of them.

Focus: Poland, Switzerland, Czech Republic

An evergreen in all biennale reviews is the exhibition's overwhelming scale, which is challenging for visitors. However, the problem seems rather to be the adaptation of exhibitors to this format. Especially in the national pavilions, one still encounters exhibitions that are well and diligently prepared but set for concentration and time, ideally requiring a whole afternoon. This includes the ambitious American pavilion this year, examining various forms of civic engagement (Dimensions of Citizenship, Giardini), which somewhat presumptively assumes familiarity with the internal tensions of the country. South Korea cannot rely on that, having traditionally prepared a very high-quality pavilion dedicated this year to the sixties (Spectres of State Avant-Garde, Giardini). Thus, we also encounter installations that may not catch the attention of most viewers at first glance, but their quality – or absence thereof – becomes apparent upon closer examination. Among the better group is the content-wise very interesting installation and accompanying publication Amplifying Nature (Poland pavilion, Giardini): contemporary authors Małgorzata Kuciewicz and Simone de Iacobis from the studio CENTRALA approach the perspective of the Anthropocene, a hypothesis that is being increasingly accepted, which posits that human alteration of the Earth’s surface can be considered a separate geological epoch. This is of course a highly architectural theme, as transforming the Earth’s surface is ultimately the main content of architecture. Through more or less experimental architectural projects, they explore how architecture can sustain and amplify natural processes, the cycle of natural light, and primarily water, which also dominates the installation. Interestingly, in addition to their own works, the authors brought into play older Polish modernists of the 60s and 70s (Oskar and Zofia Hansen, Jacek Damięcki) and, for example, demonstrated through the well-thought-out project of the Warszawianka sports complex on the outskirts of Warsaw that modernism was not insensate to these issues contrary to widely held beliefs.

Within the exhibition, however, simple and easily understandable solutions work best. The Swiss know this, and their pavilion also received the Golden Lion for the best national representation. The installation Svizzera 240 plays with the standardization of contemporary residential construction (the name derives from the usually required ceiling height). The sterile spaces of unfurnished interiors feel like a tour of a newly constructed residential building: the same doorknobs, various sockets, white doors. But soon we realize something is amiss: the scale changes. This naturally creates a disorienting impression, leading to an experience of space that is not transferable via photograph: “a place where real estate agents probably go to die,” as Oliver Wainwright wrote.

This year, attention is also drawn to UNES-CO, a project by Kateřina Šedá in the Czech, or rather Czech-Slovak pavilion (Giardini). Having recently received the title of “Architect of the Year,” the selection of this artist confirms a possible shift in the still relatively conservative perception in the Czech Republic of the boundaries of who can actively express themselves about architecture. UNES-CO is a fictional company that Šedá invented in an effort to combat the displacement of everyday life from tourist-frequented locations, often under the protection of the international organization UNESCO. The name serves as a pun in different ways in both Czech and English. Hired individuals will perform their daily activities on the streets of Český Krumlov during the summer months. The thoroughness and patience of Kateřina Šedá give hope that the “ordinary life” broadcast live to Venice, which may seem dangerously close to a reality show based on mere description, will reinforce human and community relationships as the author has successfully done in her previous projects. Thanks to some of them (Bedřichovice nad Temží, 2011–2015), she has already tested her approach abroad, and visitor responses to the Venice pavilion have so far been positive.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment

Related articles

1

02.10.2017 | The National Gallery will select an author for the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale

2

19.01.2017 | The curator of the 16th Biennale in Venice will be Grafton Architects

0

11.07.2014 | <title>The Venice Biennale 2014 - a look back at individual pavilions</title> The Venice Biennale 2014 - a look back at individual pavilions

0

09.07.2013 | HTML Translation:

```html

Working meeting on the competition conditions for the national exhibition at the 14th Architecture Biennale in Venice

```