Villa Dall'Ava

|

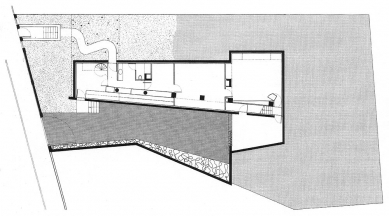

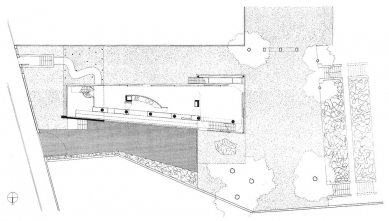

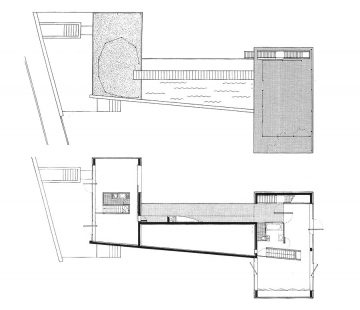

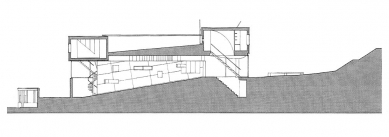

Koolhaas admits that the challenge of realization in Paris intimidated him considerably. From his text "Obstacles" in the book S,M,L,XL, we learn that "two Le Corbusier villas stand nearby" and "the client desired a masterpiece." The architect faced the challenge head-on. He focused on the more famous of the two Corbusier houses – Villa Savoye – and deconstructed it into its individual parts – the Five Points of New Architecture – which he then "remixed." The construction site for Koolhaas's building was almost the exact opposite of Savoye. The plot was narrow and flanked on both sides by family houses. Koolhaas thus took the upper floor of Savoye, cut it into two parts, which he then asymmetrically reconnected. He took the columns supporting the upper floor of Savoye, shook them up, and placed them chaotically into his design. The sunbathing area on top of Corbusier's building was replaced by a pool, and the sculpturally shaped enclosure was carelessly substituted with plastic construction fencing. This flagrant disruption of symmetry, the mixing of architectural elements approaches its grand pattern, yet simultaneously parodies it. The famous five points of Corbusier, according to which countless houses were built, are mocked. Koolhaas plays the game of being just as cool and daring as Le Corbusier once was. Koolhaas turns the seriousness of the classic upon himself without roughly or directly quoting.

At the time of its creation, Villa Dall'Ava was frequently published. It was constantly evaluated and discussed. A new media star began to slowly emerge, and as is often the case with such stars, it looks much better in photographs than in reality. Koolhaas, with a kind of modernity, achieved what postmodernism failed to do in its attempts at regressing to a period before modernity. He absorbs the power of classic events but does not submit to it. When it comes to benefiting from accumulated prestige, postmodern attempts were naive. They made no distinction between value achieved through objective verification and the principle of ancienneté (based on service tenure as opposed to seniority based on actual age). This distinction Koolhaas understands very precisely. He swears by the verified, yet he strips it of its right to seriousness. He distinguishes between meanings, classically acquired as cultural or social capital. He mocks the first one while utilizing the second meaning for his own benefit. Far deeper than with Le Corbusier, Koolhaas engaged with Mies's legacy in his later works.

Sources:

Obstacles in the book by Rem Koolhaas S,M,L,XL, Monacelli, New York 1995, pp. 132-193

Georg Franck: Mentaler Kapitalismus, Munich 2005, pp. 209-213

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment