Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences

"Few materials characterize the modernity of tomorrow as distinctly as glass." [1]

When in the autumn of 1954 N. S. Khrushchev criticized the overly decorative Soviet new buildings at a conference of builders in Moscow, and when this turnaround officially became known in our country in the first issue of Architect in 1955 as "the resolution of the Central Committee of the CPSU and the Council of Ministers of the USSR on the elimination of superfluities in design and construction", it did not yet signify a fundamental change for the domestic ideologists of socialist realism— no further instructions were forthcoming. While the neoclassicism of projects stripped of folk ornaments after this date can be compared with similar expressions of architecture around the world, it cannot, however, be compared with the main line of post-war modernism, which continued to be criticized here as "formalism." One of the few completed monumental buildings of Sorela, the Internacionál hotel in Podbaba, designed by František Jeřábek in 1952, did not open until 1958, and it was only this year that became a real milestone. In this year, the designs for Brno's buildings in the international style emerged—the hotel International (Arnošt Krejza - Miloslav Kramoliš) and the administrative building of BVV (Miroslav Spurný - Zdeněk Ševčík). Karel Prager (who had tested a Stalinist tower in a competition for the Central House of the Army as early as 1954) designed the interior of the Polish Cultural Center at the corner of Jindřišská Street and Wenceslas Square, which will be among the first domestic examples of the so-called "Brussels style." The year 1958 is primarily a year of extraordinary success for the Czechoslovak pavilion at the World Expo in this city, on which a team of architects František Cubr, Josef Hrubý, and Jaroslav Pokorný worked since 1956, along with scenographers Tröstr and Svoboda, scriptwriters Santar, and a number of visual artists—Kotík, Libenský, Brychtová, Fuka, Šimotová, or Trnka. And in 1958, Karel Prager also created the first concept for the building of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry (founded within the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in 1959) and for its first director, Otto Wichterle. [2]

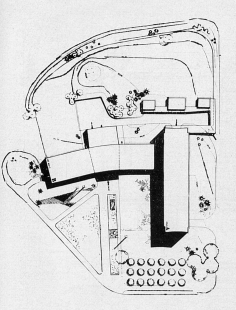

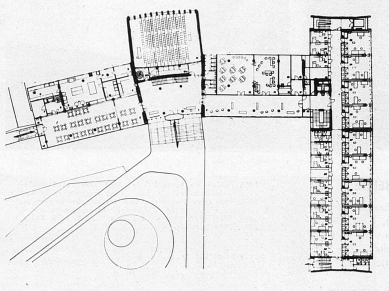

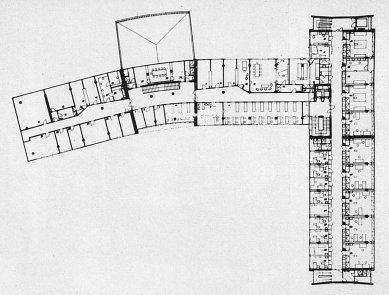

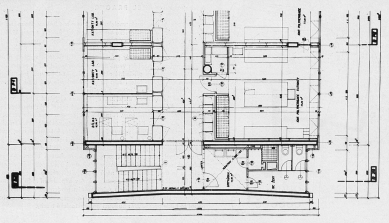

The building forms a vanishing point of the new main street of the Petřiny housing estate, developed since 1956 by a team led by Evžen Benda from the modified Kulov panel system. As the reviewer finally pointed out [3], even several Kulov maples did not completely succeed in creating the intended "green entrance area to Hvězda"—it should also be noted that the logical direction of entry into the garden was already obstructed during the First Republic by villas along Libocká Street. Further from the author's report: "Urbanistic, disposition, operational, and constructive impulses led to the creation of an independent laboratory building, to which a wing of supporting technical, community, and administrative operations is connected." Such a functional and simultaneously expressively dynamic arrangement of Prager's building was so influential in our environment that it became a reliable model for many years, encapsulated by the term "volumetric contrast" — Prager himself used it again in 1965 while designing (unfinished) complex MatFyz UK at Pelc-Tyrolka. "The outer walls consist of lightweight suspended steel panels 8 cm thick, whose thermal resistance is equivalent to a brick wall 65 cm thick." And this lightweight envelope represented perhaps the most significant novelty of this building in the Czech context—unlike the glazed walls of the Brussels pavilion, it involved a true curtain wall, developed as a prototype series thanks to Prager's resilience in domestic conditions. ("... at the Research Institute of Construction Production with Ing. Pařízek and Mr. Bor, in technical cooperation with Kovona Karviná and the plant in Boletice".) Even the so-called Boletice panels, however, over time, as the only available alternative to prefabricated concrete walls, lost their uniqueness—in common production they became weedy. Additionally, another solution required by this building due to the complex runs of laboratory operations, namely the modular partitions between laboratories and the cabinet walls of corridors, was later developed at various levels— in Prager's case to the details of the modular system of Gama panels. All these solutions are borne by the idea of technological perfection of a building assembled from parts, industrially manufactured from new materials. At the time of the first space flights, these notions were by no means unusual; the theme of the congress UIA held in London in 1961, which was also reflected upon in our country, was precisely "New technology and its influence on architecture," and Prager published an extensive article on this topic in 1963, in which he criticizes the lagging Czechoslovak construction technology, insufficiently innovative to become a source of new forms. [4] However, this "technological materialism" [5] is not fully exhausted in Prager's approach, expressed for the first time entirely in the building of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry. It is necessary to quote another of his texts again, actually just one paragraph in an article on the competition "Glass in Construction," which, however, departed from then-common writing in its diction. "The vision of modern architecture has always been associated with glass as a fundamental artistic and building element. Purity and authenticity, shimmering elegance, subtlety and warmth of reflection, cold nobility and colorful exuberance, qualitative perception of permanence and stability, objectivity and reality, transparency and crystalline clarity, as well as delicacy, pride, and grandeur are the emotional signs upon which the imagination of the style of the coming decades rests, and which are concretized in the sensations and effects of glass surfaces in architecture." [6]

Prager's architecture from this period is often associated with Mies's American buildings (Lake Shore Drive 1948-1951, Seagram Building 1954-1958), and Prager himself reportedly declared allegiance to them. [7] Mies's work undoubtedly powerfully influenced Czech architecture, although it was theoretically received quite cautiously. Even in 1961, Prager's collaborator Jiří Albrecht wrote about "the aesthetic and formalistic" aspects of Mies's work, and by 1962, architects Zdeněk Kuna, Zdeněk Stupka, and Olivier Honke-Houfek had on the boards the first version of the Strašnice building of Strojimport, which would become the first Czech pastiche of the Seagram, although it was completed only in 1972. From 1966, further Miesian buildings arose in Prague— the headquarters of Chemapol in Vršovice (Zdenka Marie Nováková - D. Šestáková) and the publishing house Albatros on Národní třída (Stanislav Franc - Luděk Hanf - Jan Nováček). In all these cases, they were already curtain walls from the Italian company FEAL. Prager's Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry, with its low wing curve and especially the "framing" of the office plate with the angular façade surface of the technical floor and vertical communication covered with a different façade grid, is rather closer to the Central European version of the international style, which we in our country, especially in relation to interior design, refer to as Brussels. [8]

The reconstruction of the building of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry was completed in 2002 according to the project of Miloslav Pavlík, Prager's long-time colleague. The original intention of the Investment Department of the ASCR to replace the technically outdated curtain walls with a replica or masonry façade was overturned not only by the intervention of Karel Prager (+ May 31, 2001) but also by the decision of the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic to register the building in the Central List of Historical Monuments (May 24, 2000). The new curtain façade of the building ultimately evokes, successfully within the investor's financial possibilities, the appearance of the original. For comparison - at the same time, the reconstruction of the Lever Building [9] (SOM, Gordon Bushaft, 1951-1952) was completed. This construction, thought to be of similar importance for architectural development in the United States as Prager's institute for the Czechoslovak environment, was declared a monument in 1992 and subsequently received new curtain walls, again designed by the office of SOM, which successfully employed today's construction method while preserving the original appearance of the building. The ground floor of the Lever Building today is adorned by the originally intended sculptural benches by Isamu Noguchi, "Makráč", and in 2005, the monument to Otto Wichterle by Michal Gabriel. "From the history of modern Czech architecture, many buildings with curtain walls have fallen out after insensitive reconstructions, but Prager's institute in Petřiny has remained among them even after its reconstruction." [10]

[1] Karel Prager, Conference "Glass in Construction," Architecture of the CSSR XX, 1961, pp. 295-298.

[2] Karel Prager, Project of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in Prague, Architecture of the CSR, XIX, 1960, pp. 528-536; Karel Prager, Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in Prague, Architecture of the CSSR XXIV, 1965, p. 653.

[3] Miroslav Koukolík, Notes on the Realization of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry, Architecture of the CSSR XXIV, 1965, pp. 656 and 658.

[4] Karel Prager, Building Technique and Architecture, Architecture of the CSSR XXII, 1963, pp. 294-296.

[5] Rostislav Švácha, Czech Architecture 1956-1963, in: Marie Judlová (ed.), Foci of Rebirth, Prague 1996, pp. 243-256, here p. 250; see also Rostislav Švácha, Architecture 1958-1970, in: Rostislav Švácha, Marie Platovská (eds.), History of Czech Visual Art VI/1, pp. 41-70, Prague 2007.

[6] Karel Prager, Glass in Construction, Architecture of the CSSR XXII, 1963, p. 385.

[7] Radomíra Sedláková, Karel Prager, Space in Time, (Exhibition Catalog at the Jaroslav Fragner Gallery), Prague 2002, p. 6.

[8] Lenka Tichá, Central European Architecture in the Years 1956-1963 and the Brussels Style, Art XLIX, 2001, No. 2, pp. 151-160.

[9] Architectural Record, June 1952.

[10] Rostislav Švácha, Pioneering Reconstruction of a Pioneering Building, Construction X, 2003, No. 1, pp. 50-51; cf.: Miloslav Pavlík, Reconstruction of the Outer and Roof Envelope of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry of the ASCR in Prague, Construction X, 2003, No. 1, pp. 52-56; Miloslav Pavlík, Reconstruction of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry of the ASCR, Architect XLIX, 2004, No. 1, pp. 14-15; Rostislav Švácha, Three Good Rehabilitations of Post-War Architecture, Reports on Monument Care LXV, 2005, No. 5, pp. 393-396.

Some texts and period photographs of the building can be found directly on the pages of the IMC.

When in the autumn of 1954 N. S. Khrushchev criticized the overly decorative Soviet new buildings at a conference of builders in Moscow, and when this turnaround officially became known in our country in the first issue of Architect in 1955 as "the resolution of the Central Committee of the CPSU and the Council of Ministers of the USSR on the elimination of superfluities in design and construction", it did not yet signify a fundamental change for the domestic ideologists of socialist realism— no further instructions were forthcoming. While the neoclassicism of projects stripped of folk ornaments after this date can be compared with similar expressions of architecture around the world, it cannot, however, be compared with the main line of post-war modernism, which continued to be criticized here as "formalism." One of the few completed monumental buildings of Sorela, the Internacionál hotel in Podbaba, designed by František Jeřábek in 1952, did not open until 1958, and it was only this year that became a real milestone. In this year, the designs for Brno's buildings in the international style emerged—the hotel International (Arnošt Krejza - Miloslav Kramoliš) and the administrative building of BVV (Miroslav Spurný - Zdeněk Ševčík). Karel Prager (who had tested a Stalinist tower in a competition for the Central House of the Army as early as 1954) designed the interior of the Polish Cultural Center at the corner of Jindřišská Street and Wenceslas Square, which will be among the first domestic examples of the so-called "Brussels style." The year 1958 is primarily a year of extraordinary success for the Czechoslovak pavilion at the World Expo in this city, on which a team of architects František Cubr, Josef Hrubý, and Jaroslav Pokorný worked since 1956, along with scenographers Tröstr and Svoboda, scriptwriters Santar, and a number of visual artists—Kotík, Libenský, Brychtová, Fuka, Šimotová, or Trnka. And in 1958, Karel Prager also created the first concept for the building of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry (founded within the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in 1959) and for its first director, Otto Wichterle. [2]

The building forms a vanishing point of the new main street of the Petřiny housing estate, developed since 1956 by a team led by Evžen Benda from the modified Kulov panel system. As the reviewer finally pointed out [3], even several Kulov maples did not completely succeed in creating the intended "green entrance area to Hvězda"—it should also be noted that the logical direction of entry into the garden was already obstructed during the First Republic by villas along Libocká Street. Further from the author's report: "Urbanistic, disposition, operational, and constructive impulses led to the creation of an independent laboratory building, to which a wing of supporting technical, community, and administrative operations is connected." Such a functional and simultaneously expressively dynamic arrangement of Prager's building was so influential in our environment that it became a reliable model for many years, encapsulated by the term "volumetric contrast" — Prager himself used it again in 1965 while designing (unfinished) complex MatFyz UK at Pelc-Tyrolka. "The outer walls consist of lightweight suspended steel panels 8 cm thick, whose thermal resistance is equivalent to a brick wall 65 cm thick." And this lightweight envelope represented perhaps the most significant novelty of this building in the Czech context—unlike the glazed walls of the Brussels pavilion, it involved a true curtain wall, developed as a prototype series thanks to Prager's resilience in domestic conditions. ("... at the Research Institute of Construction Production with Ing. Pařízek and Mr. Bor, in technical cooperation with Kovona Karviná and the plant in Boletice".) Even the so-called Boletice panels, however, over time, as the only available alternative to prefabricated concrete walls, lost their uniqueness—in common production they became weedy. Additionally, another solution required by this building due to the complex runs of laboratory operations, namely the modular partitions between laboratories and the cabinet walls of corridors, was later developed at various levels— in Prager's case to the details of the modular system of Gama panels. All these solutions are borne by the idea of technological perfection of a building assembled from parts, industrially manufactured from new materials. At the time of the first space flights, these notions were by no means unusual; the theme of the congress UIA held in London in 1961, which was also reflected upon in our country, was precisely "New technology and its influence on architecture," and Prager published an extensive article on this topic in 1963, in which he criticizes the lagging Czechoslovak construction technology, insufficiently innovative to become a source of new forms. [4] However, this "technological materialism" [5] is not fully exhausted in Prager's approach, expressed for the first time entirely in the building of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry. It is necessary to quote another of his texts again, actually just one paragraph in an article on the competition "Glass in Construction," which, however, departed from then-common writing in its diction. "The vision of modern architecture has always been associated with glass as a fundamental artistic and building element. Purity and authenticity, shimmering elegance, subtlety and warmth of reflection, cold nobility and colorful exuberance, qualitative perception of permanence and stability, objectivity and reality, transparency and crystalline clarity, as well as delicacy, pride, and grandeur are the emotional signs upon which the imagination of the style of the coming decades rests, and which are concretized in the sensations and effects of glass surfaces in architecture." [6]

Prager's architecture from this period is often associated with Mies's American buildings (Lake Shore Drive 1948-1951, Seagram Building 1954-1958), and Prager himself reportedly declared allegiance to them. [7] Mies's work undoubtedly powerfully influenced Czech architecture, although it was theoretically received quite cautiously. Even in 1961, Prager's collaborator Jiří Albrecht wrote about "the aesthetic and formalistic" aspects of Mies's work, and by 1962, architects Zdeněk Kuna, Zdeněk Stupka, and Olivier Honke-Houfek had on the boards the first version of the Strašnice building of Strojimport, which would become the first Czech pastiche of the Seagram, although it was completed only in 1972. From 1966, further Miesian buildings arose in Prague— the headquarters of Chemapol in Vršovice (Zdenka Marie Nováková - D. Šestáková) and the publishing house Albatros on Národní třída (Stanislav Franc - Luděk Hanf - Jan Nováček). In all these cases, they were already curtain walls from the Italian company FEAL. Prager's Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry, with its low wing curve and especially the "framing" of the office plate with the angular façade surface of the technical floor and vertical communication covered with a different façade grid, is rather closer to the Central European version of the international style, which we in our country, especially in relation to interior design, refer to as Brussels. [8]

The reconstruction of the building of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry was completed in 2002 according to the project of Miloslav Pavlík, Prager's long-time colleague. The original intention of the Investment Department of the ASCR to replace the technically outdated curtain walls with a replica or masonry façade was overturned not only by the intervention of Karel Prager (+ May 31, 2001) but also by the decision of the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic to register the building in the Central List of Historical Monuments (May 24, 2000). The new curtain façade of the building ultimately evokes, successfully within the investor's financial possibilities, the appearance of the original. For comparison - at the same time, the reconstruction of the Lever Building [9] (SOM, Gordon Bushaft, 1951-1952) was completed. This construction, thought to be of similar importance for architectural development in the United States as Prager's institute for the Czechoslovak environment, was declared a monument in 1992 and subsequently received new curtain walls, again designed by the office of SOM, which successfully employed today's construction method while preserving the original appearance of the building. The ground floor of the Lever Building today is adorned by the originally intended sculptural benches by Isamu Noguchi, "Makráč", and in 2005, the monument to Otto Wichterle by Michal Gabriel. "From the history of modern Czech architecture, many buildings with curtain walls have fallen out after insensitive reconstructions, but Prager's institute in Petřiny has remained among them even after its reconstruction." [10]

[1] Karel Prager, Conference "Glass in Construction," Architecture of the CSSR XX, 1961, pp. 295-298.

[2] Karel Prager, Project of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in Prague, Architecture of the CSR, XIX, 1960, pp. 528-536; Karel Prager, Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in Prague, Architecture of the CSSR XXIV, 1965, p. 653.

[3] Miroslav Koukolík, Notes on the Realization of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry, Architecture of the CSSR XXIV, 1965, pp. 656 and 658.

[4] Karel Prager, Building Technique and Architecture, Architecture of the CSSR XXII, 1963, pp. 294-296.

[5] Rostislav Švácha, Czech Architecture 1956-1963, in: Marie Judlová (ed.), Foci of Rebirth, Prague 1996, pp. 243-256, here p. 250; see also Rostislav Švácha, Architecture 1958-1970, in: Rostislav Švácha, Marie Platovská (eds.), History of Czech Visual Art VI/1, pp. 41-70, Prague 2007.

[6] Karel Prager, Glass in Construction, Architecture of the CSSR XXII, 1963, p. 385.

[7] Radomíra Sedláková, Karel Prager, Space in Time, (Exhibition Catalog at the Jaroslav Fragner Gallery), Prague 2002, p. 6.

[8] Lenka Tichá, Central European Architecture in the Years 1956-1963 and the Brussels Style, Art XLIX, 2001, No. 2, pp. 151-160.

[9] Architectural Record, June 1952.

[10] Rostislav Švácha, Pioneering Reconstruction of a Pioneering Building, Construction X, 2003, No. 1, pp. 50-51; cf.: Miloslav Pavlík, Reconstruction of the Outer and Roof Envelope of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry of the ASCR in Prague, Construction X, 2003, No. 1, pp. 52-56; Miloslav Pavlík, Reconstruction of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry of the ASCR, Architect XLIX, 2004, No. 1, pp. 14-15; Rostislav Švácha, Three Good Rehabilitations of Post-War Architecture, Reports on Monument Care LXV, 2005, No. 5, pp. 393-396.

Some texts and period photographs of the building can be found directly on the pages of the IMC.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

5 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

Rekonstrukce

ježek

26.11.13 09:05

ad Rekonstrukce

IK

27.11.13 01:34

Rekonstrukce 2

ježek

27.11.13 08:09

Idealismus

IK

28.11.13 11:45

Opakovat chyby, či je napravovat?

Dr.Lusciniol

29.11.13 12:45

show all comments