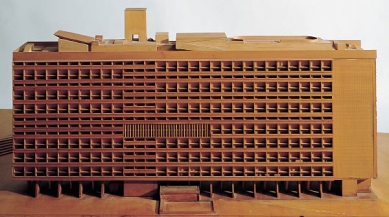

Unit of Housing Marseille

Cité Radieuse

Residential Unit in Marseille

The Construction of the Transatlantic Liner

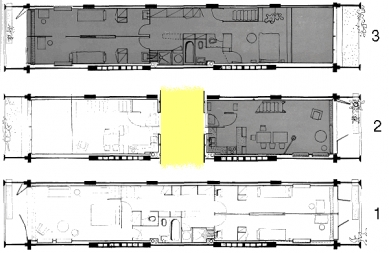

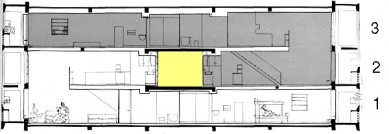

The realization of the Unit in Marseille showcased the splendor achievable through the use of reinforced concrete as a natural material of the same value as stone, wood, or terracotta. It truly seems possible to regard concrete as restored stone, and it is worth exposing it to sight in its natural state. It is said that due to the cement, it is bland, meaning its color is bland. This is just as misleading as saying that color is bland in itself, when in fact colors gain value only in relation to their surroundings.

The unit in Marseille took five arduous years to construct and was constantly hindered by various circumstances; coordination was lacking, and indifferent workers—even those skilled in their own trades—were unable to adjust to one another. For example, the concrete workers and carpenters who created the formwork did their jobs under the impression that imperfections (as is usually the case) could be improved with a trowel, that they could be plastered over or tinted, until the formwork was taken down. The defects scream at us from all parts of the building! Fortunately, we didn't have the money for it!

But even with money, the problem of repairing defects would not have seemed solvable. Plaster or smoothed cement would merely disfigure the surface of the building without correcting the mistakes. Exposed concrete reveals the slightest episodes in formwork, seams of boards, fibers, and knots of wood, etc. But how noble these things are when we look at them, how interesting when we observe them, how surely they enrich those who have a bit of imagination.

How often visitors (especially Swiss, Dutch, and Swedes) told me: “Your building is very beautiful, but how poorly it was executed,” and I would reply, “Have you never noticed at cathedrals or castles how roughly shaped the stones are, the acknowledged imperfections clearly displayed for all to see? Have you not accidentally noticed such things when you were looking at architecture? Don't you see wrinkles and moles, crooked noses, countless peculiarities even in men and women? Do you not expect to encounter the Venus of Medici made of flesh and blood—Apollo of Belvedere?”

Mistakes are human; they are indeed our everyday lives. What matters is to move on, to live, to be strong, to aim higher, and to be faithful!

I devised a way to deal with the worst flaw of the Unit in Marseille, which is the railing of the ramp leading up to the children's corner on the roof. I decided to evoke beauty through contrast. I found its complement and established a play between roughness and finesse, between dullness and potency, between precision and chance. I will do it in such a way that people think and reflect, and that is the reason for the bold, loud, victorious polychromy of the façades in Marseille—thanks to no small courage and a new and noble product “matroil”.

I achieved that the ministry paid a small amount to a concrete worker from Sardinia who understood his craft. Concrete deteriorates only due to ignorance and not because of its own faults. In craftsmanship here, poor taste prevails, and there are craftsmen with poor taste. In a similar case, I had to apply indomitable energy to ensure that the state employed a concrete worker whom I trust, who accepts orders directly from me and understands them. I proposed certain parts of the building in a way that requires them to be modeled with a trowel—the craftsman then works like a sculptor, directly shaping the material. By arranging the color and using the trowel, contrasts were created, and the splendors of naked concrete were realized!

The unit in Marseille took five arduous years to construct and was constantly hindered by various circumstances; coordination was lacking, and indifferent workers—even those skilled in their own trades—were unable to adjust to one another. For example, the concrete workers and carpenters who created the formwork did their jobs under the impression that imperfections (as is usually the case) could be improved with a trowel, that they could be plastered over or tinted, until the formwork was taken down. The defects scream at us from all parts of the building! Fortunately, we didn't have the money for it!

But even with money, the problem of repairing defects would not have seemed solvable. Plaster or smoothed cement would merely disfigure the surface of the building without correcting the mistakes. Exposed concrete reveals the slightest episodes in formwork, seams of boards, fibers, and knots of wood, etc. But how noble these things are when we look at them, how interesting when we observe them, how surely they enrich those who have a bit of imagination.

How often visitors (especially Swiss, Dutch, and Swedes) told me: “Your building is very beautiful, but how poorly it was executed,” and I would reply, “Have you never noticed at cathedrals or castles how roughly shaped the stones are, the acknowledged imperfections clearly displayed for all to see? Have you not accidentally noticed such things when you were looking at architecture? Don't you see wrinkles and moles, crooked noses, countless peculiarities even in men and women? Do you not expect to encounter the Venus of Medici made of flesh and blood—Apollo of Belvedere?”

Mistakes are human; they are indeed our everyday lives. What matters is to move on, to live, to be strong, to aim higher, and to be faithful!

I devised a way to deal with the worst flaw of the Unit in Marseille, which is the railing of the ramp leading up to the children's corner on the roof. I decided to evoke beauty through contrast. I found its complement and established a play between roughness and finesse, between dullness and potency, between precision and chance. I will do it in such a way that people think and reflect, and that is the reason for the bold, loud, victorious polychromy of the façades in Marseille—thanks to no small courage and a new and noble product “matroil”.

I achieved that the ministry paid a small amount to a concrete worker from Sardinia who understood his craft. Concrete deteriorates only due to ignorance and not because of its own faults. In craftsmanship here, poor taste prevails, and there are craftsmen with poor taste. In a similar case, I had to apply indomitable energy to ensure that the state employed a concrete worker whom I trust, who accepts orders directly from me and understands them. I proposed certain parts of the building in a way that requires them to be modeled with a trowel—the craftsman then works like a sculptor, directly shaping the material. By arranging the color and using the trowel, contrasts were created, and the splendors of naked concrete were realized!

Le Corbusier. The Complete Architectural Works, Volume V, 1946-52. Willy Boesiger. Thames and Hudson, London 1953, p.191, translated by Professor Rostislav Švácha.

The Construction of the Transatlantic Liner

Just as airplanes represent significant elements of national propaganda, so too do liners. Many countries around the world engage their best ideas, best techniques, and best products to surpass records of intelligence, spirit, or power.

The elements of propaganda that seemed most entrenched gave way to entirely new perspectives brought about by the astonishing development of machine civilization within a few years.

One of the first victims of this transformation is France. Through a simple play of languages, France lost a significant lead over the Anglo-Saxon world. It retained the prestige of its creators (French creative spirit). But France still coyly mocks those inventors of theirs who carry the prestige of their country abroad. France decides to recognize the worth of those who dedicated their lives to research only after a very delayed turn. France was notorious for good taste, that is true. However, official good taste is not the kind of good taste accepted abroad. Remarks made in some countries indicate coldness, irony, or even contempt. I have often heard them; I will not quote them... Heads of national institutions, consecrated and certainly marked by an unpleasant delay compared to contemporary developments, do not know such a state of mind or such judgments. Official officials inform each other among themselves, and thus due to a twenty to thirty-year delay, our country slips into disrespect among international elites.

In our subject (transatlantic liners), a striking example is the “Normandie.” This ship is an elegant vessel, an efficient mechanism, a friendly luxury restaurant, but the style of its architecture was judged strictly and left passengers feeling boredom that the festivities held on board could not dispel. The French were very happy, but foreigners criticized.

Recently, architecture has made a tremendous leap forward around the world. A typical example is the Residential Unit in Marseille, which was vilified, criticized, and fiercely battled for five years to the point that the project was threatened with failure. Today, it is the subject of the most favorable comments from all major foreign reviews, and those who visited it must admit that a tremendous step has been made. Only incredible statements from the official authorities of French architecture and hygiene linger like real burdens on this project.

What is the transatlantic liner? It is a ship, a means of penetrating into the waves and into the air. It is propulsion, a mechanical creation. Finally, it is a luxury restaurant, a magnificent hotel that must satisfy 2000 people under conditions of extraordinary closeness and modesty. This takes place amidst waves, in a storm, or conversely in complete calm.

Up to this time, the psychology of the client (the passengers) has been tinged with fear: storms, infamous shipwrecks, and above all, seasickness. (...)

Seasickness has a highly nervous nature, induced by both physical and psychological reactions: psychological factors of uncertainty, fear, and anxiety predominate. Just as earlier French architecture offers transatlantic travelers salons, huge dining halls (the cathedral dining hall of “Normandie,” where guests looked like miserable people crushed by such useless ostentation, so reminiscent of the palace in Versailles or the decorative arts exhibition in 1925) with stone staircases, wrought iron ramps, marble pilasters, and when these pilasters, these staircases leave the vertical, tilting alternately to the left and to the right, the passengers feel ill. We must not realize “terrestrial” architecture on the skeleton of a floating and swaying ship.

Life on board (the life of the passengers) must correspond to a specific concept of a luxury floating restaurant. Passengers must feel pleasantly as if on a ship and not as in a terrestrial swaying palace. And the nature of the cabins, the nature of the corridors, decks, and salons must confirm for them that they are at sea; the joy of being at sea, with a constantly moving horizontal line and a vertical that exists only in the doorway between two opposite oscillations. (...)

Another problem, no less important, is the issue of dignity and then pride in the silhouette of the transatlantic liner. Here lies a great game. The error that occurred with “Normandie” lies in its third funnel, which gave it the appearance of an old steamer and not at all the silhouette demanded by speed, mechanics, and aerodynamics. Some countries, particularly Italy, have already addressed this major issue, the silhouette of the vessel as it appears on the waves. It is a matter of harmony that can arise only from the true miracle of finding proportion. It concerns the issue of ship sculpture that can only be created by a sculptor who is connected with technique and is familiar with materials and physical problems. To realize such a thing, this ability to conceive must be found in a single person.

The key to solving the aforementioned problem of harmony lies in numbers, that is, the unit in geometry and mathematics, entering into the realization of the work in full measure, from the dimensions of the window of the doors to the overall silhouette of the vessel. The creation of modern times, recognized now and used all over the world, a creation that provides the designer with a useful tool to find proportion, is the Modulor. This Modulor, a harmonic measure corresponding to the human scale, universally applicable in Architecture as well as in Mechanics, created from 1942 to 1948, was created to fill the significant gap that hindered the production of coordinated harmonic and harmonizing series. The application of the Modulor brings a lightness incomparable to drawing or construction, helping us out of uncertainty and also solving the absence of method in this field. (...)

A typical building for the use of the Modulor is the transatlantic liner, as the coordination of all dimensions thus becomes automatic.

The realization of Residential Units, such as the one in Marseille, which is already in use, seems to be a real triumph and becomes a significant part of French propaganda abroad. The work in Nantes, currently in progress, the work in Briey, currently being prepared, indicate a spiritual turn that we should appeal to in the realization of the transatlantic liner, this similar problem (in terms of service provided to users).

To achieve such a spiritual turnaround, we must devote special attention to it throughout our entire lives. We must create an organization capable of bringing its influence externally. This means we need to create a drawing studio, where we can find collaborators engaged in the same spiritual turnaround and capable of working in absolute cohesion. These factors unite in the studio at 35 de Sévres street, in a studio that has created an enormous volume of designs for the equipment of machine civilization over 32 years. This studio is intended to face the grand problems of the construction of a transatlantic liner that is to impress public opinion.

The elements of propaganda that seemed most entrenched gave way to entirely new perspectives brought about by the astonishing development of machine civilization within a few years.

One of the first victims of this transformation is France. Through a simple play of languages, France lost a significant lead over the Anglo-Saxon world. It retained the prestige of its creators (French creative spirit). But France still coyly mocks those inventors of theirs who carry the prestige of their country abroad. France decides to recognize the worth of those who dedicated their lives to research only after a very delayed turn. France was notorious for good taste, that is true. However, official good taste is not the kind of good taste accepted abroad. Remarks made in some countries indicate coldness, irony, or even contempt. I have often heard them; I will not quote them... Heads of national institutions, consecrated and certainly marked by an unpleasant delay compared to contemporary developments, do not know such a state of mind or such judgments. Official officials inform each other among themselves, and thus due to a twenty to thirty-year delay, our country slips into disrespect among international elites.

In our subject (transatlantic liners), a striking example is the “Normandie.” This ship is an elegant vessel, an efficient mechanism, a friendly luxury restaurant, but the style of its architecture was judged strictly and left passengers feeling boredom that the festivities held on board could not dispel. The French were very happy, but foreigners criticized.

Recently, architecture has made a tremendous leap forward around the world. A typical example is the Residential Unit in Marseille, which was vilified, criticized, and fiercely battled for five years to the point that the project was threatened with failure. Today, it is the subject of the most favorable comments from all major foreign reviews, and those who visited it must admit that a tremendous step has been made. Only incredible statements from the official authorities of French architecture and hygiene linger like real burdens on this project.

What is the transatlantic liner? It is a ship, a means of penetrating into the waves and into the air. It is propulsion, a mechanical creation. Finally, it is a luxury restaurant, a magnificent hotel that must satisfy 2000 people under conditions of extraordinary closeness and modesty. This takes place amidst waves, in a storm, or conversely in complete calm.

Up to this time, the psychology of the client (the passengers) has been tinged with fear: storms, infamous shipwrecks, and above all, seasickness. (...)

Seasickness has a highly nervous nature, induced by both physical and psychological reactions: psychological factors of uncertainty, fear, and anxiety predominate. Just as earlier French architecture offers transatlantic travelers salons, huge dining halls (the cathedral dining hall of “Normandie,” where guests looked like miserable people crushed by such useless ostentation, so reminiscent of the palace in Versailles or the decorative arts exhibition in 1925) with stone staircases, wrought iron ramps, marble pilasters, and when these pilasters, these staircases leave the vertical, tilting alternately to the left and to the right, the passengers feel ill. We must not realize “terrestrial” architecture on the skeleton of a floating and swaying ship.

Life on board (the life of the passengers) must correspond to a specific concept of a luxury floating restaurant. Passengers must feel pleasantly as if on a ship and not as in a terrestrial swaying palace. And the nature of the cabins, the nature of the corridors, decks, and salons must confirm for them that they are at sea; the joy of being at sea, with a constantly moving horizontal line and a vertical that exists only in the doorway between two opposite oscillations. (...)

Another problem, no less important, is the issue of dignity and then pride in the silhouette of the transatlantic liner. Here lies a great game. The error that occurred with “Normandie” lies in its third funnel, which gave it the appearance of an old steamer and not at all the silhouette demanded by speed, mechanics, and aerodynamics. Some countries, particularly Italy, have already addressed this major issue, the silhouette of the vessel as it appears on the waves. It is a matter of harmony that can arise only from the true miracle of finding proportion. It concerns the issue of ship sculpture that can only be created by a sculptor who is connected with technique and is familiar with materials and physical problems. To realize such a thing, this ability to conceive must be found in a single person.

The key to solving the aforementioned problem of harmony lies in numbers, that is, the unit in geometry and mathematics, entering into the realization of the work in full measure, from the dimensions of the window of the doors to the overall silhouette of the vessel. The creation of modern times, recognized now and used all over the world, a creation that provides the designer with a useful tool to find proportion, is the Modulor. This Modulor, a harmonic measure corresponding to the human scale, universally applicable in Architecture as well as in Mechanics, created from 1942 to 1948, was created to fill the significant gap that hindered the production of coordinated harmonic and harmonizing series. The application of the Modulor brings a lightness incomparable to drawing or construction, helping us out of uncertainty and also solving the absence of method in this field. (...)

A typical building for the use of the Modulor is the transatlantic liner, as the coordination of all dimensions thus becomes automatic.

The realization of Residential Units, such as the one in Marseille, which is already in use, seems to be a real triumph and becomes a significant part of French propaganda abroad. The work in Nantes, currently in progress, the work in Briey, currently being prepared, indicate a spiritual turn that we should appeal to in the realization of the transatlantic liner, this similar problem (in terms of service provided to users).

To achieve such a spiritual turnaround, we must devote special attention to it throughout our entire lives. We must create an organization capable of bringing its influence externally. This means we need to create a drawing studio, where we can find collaborators engaged in the same spiritual turnaround and capable of working in absolute cohesion. These factors unite in the studio at 35 de Sévres street, in a studio that has created an enormous volume of designs for the equipment of machine civilization over 32 years. This studio is intended to face the grand problems of the construction of a transatlantic liner that is to impress public opinion.

Report on the construction of the transatlantic liner addressed to the president of the General Transatlantic Company, Paris, October 30, 1953.

Le Corbusier, le passé réaction poétique, Le Corbusier, Paris 1987, pp.189-91, translated by Kateřina Jandová.The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment