Project of the Congress Palace in Venice

Palace of Congresses

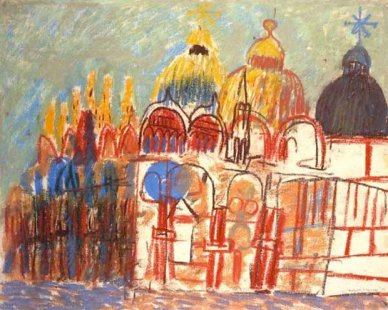

Venice decided in 1968 to commission a project for a new congress palace from the Estonian-born architect Louis Kahn. The unique city built on oak piles perfectly preserves the architectural legacy of the past millennium, but there is very little room for new buildings, and it is rare for projects of such scale to be realized. Before Kahn, a similar opportunity was given to Le Corbusier, who, during the time of great growth in the Italian economy, prepared a proposal for a new hospital in 1965.

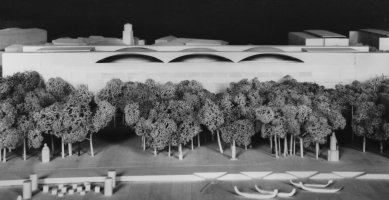

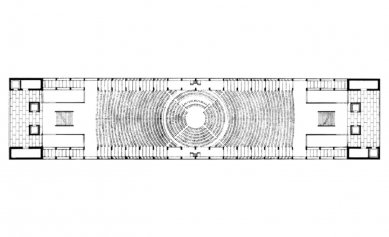

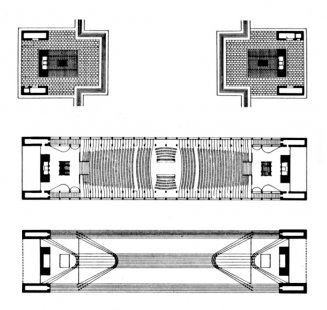

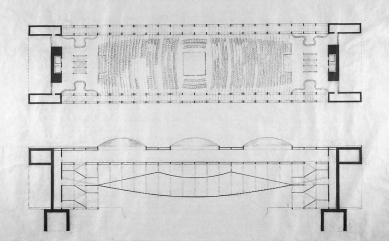

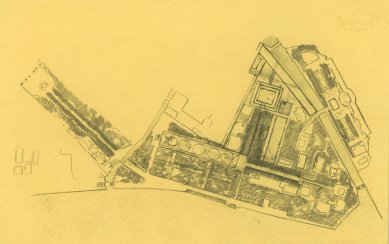

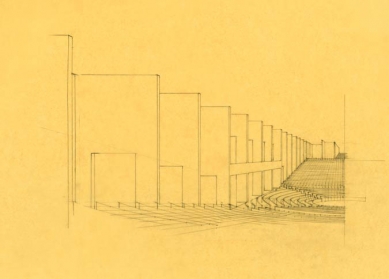

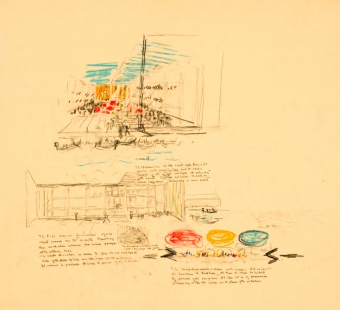

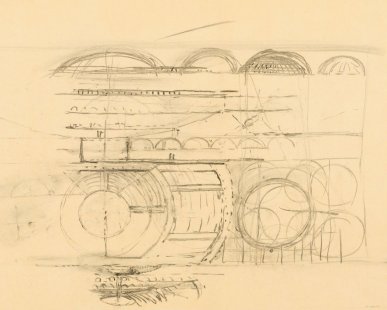

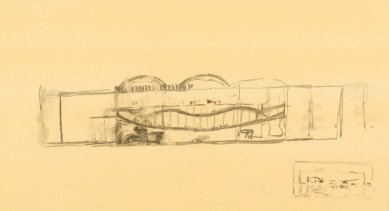

The original site was located in Giardini Park, but later the congress center was moved to the former military complex of Arsenale. The new design involved spanning the Canale delle Galeazze. With a bold gesture, it connected the two shores. A public institution as a bridge and an accompanying public space in the form of an open rooftop terrace. A strong concept that Kahn was able to develop into a simple form does not lose its drama. The mass consists of two volumes with staircore shafts, elegantly carrying a gracefully curved concrete slab across the water channel, upon which the main hall of the congress palace rests. A place where public discussions about the city and its inhabitants take place. The hall is glazed on both sides. Thus, it is possible to see through the entire building. This sends a signal outward that the building is transparent, as are the discussions held within it. The entire structure is reflected in the water surface of the canal.

What fascinates me about Kahn is how incredibly sensitively he works with materials to create buildings with a strong expression, appearing monumental yet simultaneously human. It seems he succeeded in bridging that modernist chasm, which rejected all historicisms, and connecting to ancient building artistry, interpreting it in the twentieth century. To create architecture as a connection, instead of architecture around the circulation of life. To create real places with an atmosphere instead of merely functional spaces. Not to seek universal truth, but rather a balance between reciprocal quantities.

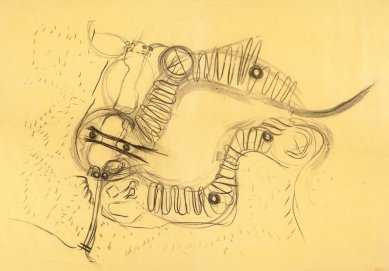

The design was rejected by the city council upon its completion and thus became one of Kahn's other unrealized projects. However, this does not mean that the project does not continue to live its life. From his hand-drawn plans, one can feel great energy. Floor plans drawn in charcoal, meticulously thought-out construction details, or atmospheric sketches of the interior. From all this, one can easily trace how Kahn thought about the project and elaborated on his ideas. Perhaps that is why his projects are an eternal inspiration for new generations of architects. For a long time, I believed that architecture is only what becomes reality. Considering the impact an unrealized project can have on society, I must admit that such a perspective on architecture would be very narrow-minded. After all, even an unrealized project in the shape of a bizarre octopus can spark a debate about architecture that lasts for years. Kahn believed in the power of unrealized projects, as evidenced by this quote: “What was not built is not truly lost. Once the value of a work is created, its claim to existence is undeniable.” So what does it really mean for a project to be real?

Just as I see the national assembly building in Dhaka, I understand the Palazzo dei Congressi as a symbol. A symbol of the common interest of the people of a certain territory to decide on public matters democratically based on common discussion. It is also a symbol of the maturity of this society, as a functioning democracy is undoubtedly a sign of advancement.

The original site was located in Giardini Park, but later the congress center was moved to the former military complex of Arsenale. The new design involved spanning the Canale delle Galeazze. With a bold gesture, it connected the two shores. A public institution as a bridge and an accompanying public space in the form of an open rooftop terrace. A strong concept that Kahn was able to develop into a simple form does not lose its drama. The mass consists of two volumes with staircore shafts, elegantly carrying a gracefully curved concrete slab across the water channel, upon which the main hall of the congress palace rests. A place where public discussions about the city and its inhabitants take place. The hall is glazed on both sides. Thus, it is possible to see through the entire building. This sends a signal outward that the building is transparent, as are the discussions held within it. The entire structure is reflected in the water surface of the canal.

What fascinates me about Kahn is how incredibly sensitively he works with materials to create buildings with a strong expression, appearing monumental yet simultaneously human. It seems he succeeded in bridging that modernist chasm, which rejected all historicisms, and connecting to ancient building artistry, interpreting it in the twentieth century. To create architecture as a connection, instead of architecture around the circulation of life. To create real places with an atmosphere instead of merely functional spaces. Not to seek universal truth, but rather a balance between reciprocal quantities.

The design was rejected by the city council upon its completion and thus became one of Kahn's other unrealized projects. However, this does not mean that the project does not continue to live its life. From his hand-drawn plans, one can feel great energy. Floor plans drawn in charcoal, meticulously thought-out construction details, or atmospheric sketches of the interior. From all this, one can easily trace how Kahn thought about the project and elaborated on his ideas. Perhaps that is why his projects are an eternal inspiration for new generations of architects. For a long time, I believed that architecture is only what becomes reality. Considering the impact an unrealized project can have on society, I must admit that such a perspective on architecture would be very narrow-minded. After all, even an unrealized project in the shape of a bizarre octopus can spark a debate about architecture that lasts for years. Kahn believed in the power of unrealized projects, as evidenced by this quote: “What was not built is not truly lost. Once the value of a work is created, its claim to existence is undeniable.” So what does it really mean for a project to be real?

Just as I see the national assembly building in Dhaka, I understand the Palazzo dei Congressi as a symbol. A symbol of the common interest of the people of a certain territory to decide on public matters democratically based on common discussion. It is also a symbol of the maturity of this society, as a functioning democracy is undoubtedly a sign of advancement.

David Zatloukal

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment