The Pavilion / Norman Foster Foundation

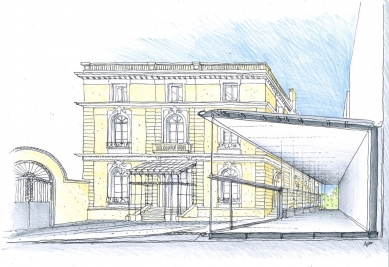

The Norman Foster Foundation, which officially opened its headquarters in a heritage-listed residential Palace by Joaquín Saldaña in Madrid on 1 June, has opened a new pavilion in its courtyard that will show a changing display of objects and images that have, over the years, been personal references for Foster. The flexible space will also be the setting for talks and discussion groups, and features a façade that can open to the courtyard for outdoor events.

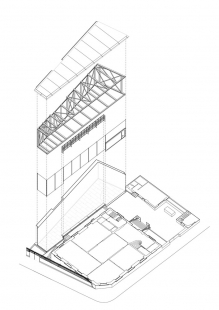

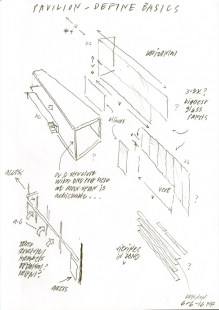

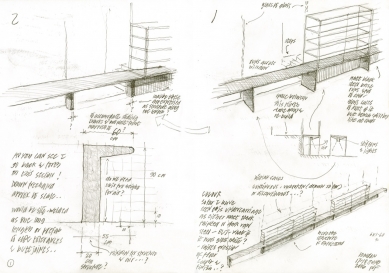

The new building resolves the irregular geometry of the outdoor area with a roof shaped like the wing of an aircraft. This is supported by a hidden steel structure cantilevered over a structural glass façade without any visible means of support so the roof seems to oat over it. The result is an architecture which seeks the ephemeral qualities of light, lightness and reflections. Elements are reduced to an essential minimum with a mirrored ceiling and fascia which further dissolves the volume of space to emphasise its contents.

The courtyard and entrance façade of the pavilion is shaded by a canopy created by the Spanish artist Cristina Iglesias. This work, The Ionosphere (A Place of Silent Storms), is composed of interlocking light carbon bre panels with patterns generated from a text of Arthur C. Clarke’s The Fountains of Paradise. It frames the view of the court from the pavilion as well as bathing it in dappled shade.

From its innovative but understated use of glass, steel and composite materials, the pavilion is a further exploration of techniques that Norman Foster has pioneered over more than ve decades. The wide glass panel to the courtyard next to the entrance is itself a massive door, weighing 2.7 tons and 6 metres long. When this portal is opened up the interior and exterior worlds are united into one owing space for Foundation gatherings.

By working closely with the craftsmen in metal and glass it has been possible to develop a combination of slim bead-blasted stainless steel sections welded together and with mirror polished edges which dematerialise the bulk of supporting structures.

The contents of the pavilion are an eclectic selection of objects, models, photography and sculpture from the worlds of art, architecture and design, embracing aircraft, cars and locomotives. For Norman Foster these are not separate worlds but interconnected with a special emphasis on his passion for ight. The display is also an opportunity to acknowledge the importance to Foster of other architects, engineers and mentors from the past as well as the present.

An important and historic car is displayed for the rst time. This is not a replica - it is the newly restored and original 1927 Avions Voisin C7 that was owned by Le Corbusier and featured in photographs of all his early works. The car was very advanced in its time using aviation technology pioneered by Voisin for his ying machines. Because of its large expanse of glass, echoed in the new architecture of its age, it was called the Lumineuse. Gabriel Voisin was also a patron of Le Corbusier who named his radical proposal for Paris The Voisin Plan.

The pavilion was realised through detail design and construction in six months. This was made possible by prefabricating all the elements which also avoided excavation on the site and disruption to neighbours. The high thermal performance of the glass building envelope, radiant heating and cooling through the oor, generous external shading and the latest generation of LED lighting are all part of its sustainable agenda.

The Norman Foster Foundation is separate from the practice of Norman Foster - the architects for the pavilion are a design studio based within the Madrid Foundation and led by Foster. Local skills and materials have been important – for example eleven of the twelve consultants are from Spain and six of the nine contractors and suppliers are Spanish – the remainder from Italy, Germany and Japan.

The new building resolves the irregular geometry of the outdoor area with a roof shaped like the wing of an aircraft. This is supported by a hidden steel structure cantilevered over a structural glass façade without any visible means of support so the roof seems to oat over it. The result is an architecture which seeks the ephemeral qualities of light, lightness and reflections. Elements are reduced to an essential minimum with a mirrored ceiling and fascia which further dissolves the volume of space to emphasise its contents.

The courtyard and entrance façade of the pavilion is shaded by a canopy created by the Spanish artist Cristina Iglesias. This work, The Ionosphere (A Place of Silent Storms), is composed of interlocking light carbon bre panels with patterns generated from a text of Arthur C. Clarke’s The Fountains of Paradise. It frames the view of the court from the pavilion as well as bathing it in dappled shade.

From its innovative but understated use of glass, steel and composite materials, the pavilion is a further exploration of techniques that Norman Foster has pioneered over more than ve decades. The wide glass panel to the courtyard next to the entrance is itself a massive door, weighing 2.7 tons and 6 metres long. When this portal is opened up the interior and exterior worlds are united into one owing space for Foundation gatherings.

By working closely with the craftsmen in metal and glass it has been possible to develop a combination of slim bead-blasted stainless steel sections welded together and with mirror polished edges which dematerialise the bulk of supporting structures.

The contents of the pavilion are an eclectic selection of objects, models, photography and sculpture from the worlds of art, architecture and design, embracing aircraft, cars and locomotives. For Norman Foster these are not separate worlds but interconnected with a special emphasis on his passion for ight. The display is also an opportunity to acknowledge the importance to Foster of other architects, engineers and mentors from the past as well as the present.

An important and historic car is displayed for the rst time. This is not a replica - it is the newly restored and original 1927 Avions Voisin C7 that was owned by Le Corbusier and featured in photographs of all his early works. The car was very advanced in its time using aviation technology pioneered by Voisin for his ying machines. Because of its large expanse of glass, echoed in the new architecture of its age, it was called the Lumineuse. Gabriel Voisin was also a patron of Le Corbusier who named his radical proposal for Paris The Voisin Plan.

The pavilion was realised through detail design and construction in six months. This was made possible by prefabricating all the elements which also avoided excavation on the site and disruption to neighbours. The high thermal performance of the glass building envelope, radiant heating and cooling through the oor, generous external shading and the latest generation of LED lighting are all part of its sustainable agenda.

The Norman Foster Foundation is separate from the practice of Norman Foster - the architects for the pavilion are a design studio based within the Madrid Foundation and led by Foster. Local skills and materials have been important – for example eleven of the twelve consultants are from Spain and six of the nine contractors and suppliers are Spanish – the remainder from Italy, Germany and Japan.

0 comments

add comment