Lidice Memorial - new audiovisual exhibition

The tragedy of Lidice in June 1942, when this village was annihilated and razed to the ground in an act of revenge after the assassination of R. Heydrich, once sparked a response and a wave of solidarity across the world. Human memory, however, is a cultural matter. It is tied to language, thought, the interpretation of history, as well as the very act of remembering. If after 1989 the commemoration of Lidice was threatened by its association with the communist regime, which appropriated it as one of the symbols of its own ideology, and the newly transforming country turned away from it for a time, then the creators of the current reconstruction of the memorial and museum are trying to approach this sad event in our past more in a cathartic than a descriptive manner, excluding any political ideology.

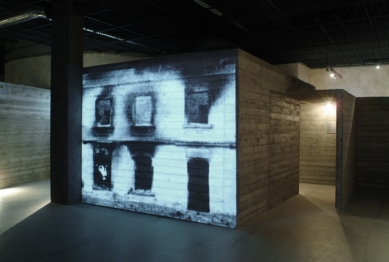

However, it is questionable to what extent such an approach is even possible. Since the museum's exhibition is primarily based on period photographs, archival film material, and admittedly newly shot material, even the projection in the circular entrance chamber is a sort of interpretation of history, placing the Lidice tragedy within the context of the global political situation. The projection takes place simultaneously on three screens placed next to each other, where images of global events are combined with pictures of everyday life, sometimes arranged together in overly conventional ways. Work in the fields and in factories, the First Republic with its icon T. G. Masaryk, the crash on the New York Stock Exchange, Hitler's rise to power, the occupation of Czechoslovakia, war... until the collage culminates in the very comparison of Lidice with the ground. The combination of the three screens, a technique once invented by Abel Gance for his historical film "Napoleon," protects the projection from superficial interpretation, forcing the viewer to jump their gaze from screen to screen, collaborating in connecting individual scenes, and preventing nostalgic repose in their age. Through the rapid cuts occurring between the screens, along with the aggressive sound component of war and the darkly rumbling crowds, considerable expressive impact is achieved in the eight-minute film. After we "take in" the final panoramic view of the burned Lidice, we can enter the museum's exhibition itself.

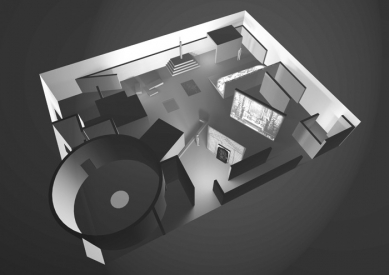

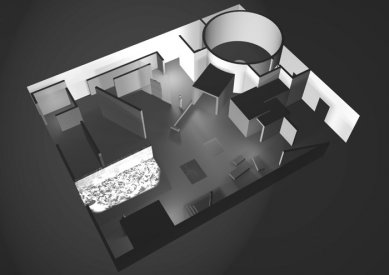

We find ourselves in a dimly lit rectangular hall with rough plastered walls showing traces of circular smoothing movements. The technical equipment of the room, including the air conditioning and data projectors, is equally transparently acknowledged.

The room is divided by monolithic concrete panels, creating various nooks, loops, and chambers that irregularly run along the walls. The imaginary, conceptual, rather than geometric center of the room is formed by the gates of the former Lidice church, which fortuitously survived, and the large concrete slab behind them onto which a photograph of the altar is projected. It serves as a conceptual center representing a return to something that was overturned and which, as the exhibition's authors likely believe, is undeniable. It creates a virtual space of a temple, raised above the relics of preserved objects, around which both ordinary and horrifying scenes unfold, perhaps serving as a manifestation of the desire for the restoration of a brutally disrupted order.

As we walk along the walls and visit individual chambers, we chronologically traverse the history suggested by the initial image, with its symbolic representation also being the gas chamber. This history is composed of further edited short films, each dedicated to a specific phase of the development of the causes of the massacre's tragedy.

However, the arrangement of the exhibition also has a different meaning than mere chronology. Apart from several solemnly displayed items that survived from the village and escaped destruction, nearly the entire exhibition consists of images, both static and moving, projected onto concrete slabs and thus by light. It is a kind of fragility, immateriality, and unreality of the projected photograph, which is supported by concrete blocks, a process not unlike the ancient Greek mystical principle of the emanation of divine light through darkness and its permeation of matter in the act of creation. Here too, light gives rise to a flickering of images on the surface of the concrete, which, however, simultaneously destroys the images, as traces of the wooden boards in which the slabs were cast emerge to the surface, along with various blemishes and pores of the material. The idea, the memory, the act of reverence—all require matter for their creation, unfolding on its surface, while also remaining vulnerable, immaterial, threatened by extinction, non-existence. Despite the endless repetition of loops of films reminiscent of the obsessive fixation of "tormenting memories," we sense that it only takes turning off the data projectors for bare, brutal, and cold concrete to remain. The act of remembering, of thinking, requires effort; the spiritualizing of matter is thus not merely a mechanical affair.

However, it is primarily the content of the images that is oppressive. As we walk along the walls, we first encounter small snapshots that have survived from the village. Images of residents, men, women, and children, captured on solid material, all in such small formats that voyeuristic access to the matter is prevented, compelling the visitor to approach the concrete wall and extract the image from it with their attention. The only exception is a large-format photograph of students in a classroom. Here I cannot refrain from a small criticism. While it is indeed preserved material and a selection from it, trivial images such as ducks on the water or a dog with glasses sitting in a chair belong to the traces of everyday life in Lidice; however, within the entire exhibition based on the necessity of increasing the attention paid to the images, they seem somewhat out of place. The images of children, which appear in several sectors, are also unnecessarily overused, as it seems to me at least, introducing unnecessary sentiment even where the authors otherwise managed to avoid it.

Following are film images and collages of Heydrich's aggressive proclamations threatening to erase the Slavic race from the surface of the usurped land, wartime scenes, Czechoslovak units in England from which the assassins were recruited, the assassination of Heydrich itself, and his subsequent burial in Berlin along with the dead paratroopers.

The day after Heydrich's funeral, the Lidice massacre took place. We stand over a concrete embankment, in which bodies of shot men are projected. The blurriness of the photograph does not allow us to discern the details of the image, yet even here, we are prevented from disturbing the dead with our curiosity. As we approach the image, the projector placed behind us casts our own shadow onto the surface. The image disappears behind its outlines, and we ourselves, with our own bodies, become part of the realm of the dead, the valley of shadows. It is an extremely disturbing feeling, a phenomenon that haunts us throughout the exhibition and contributes to the intensification of a stifling atmosphere.

The next part of the exhibition is dedicated to familiarizing oneself with the individuality of the murdered, as far as the view on the light imprint of a human face in photochemical material allows and distinguishes it from the mass of the common grave. Small, period portrait photographs running in a thin line along the wall, faces of the 199 executed with attached names. In these places, the walls are equipped with a low ceiling, as if we were finding ourselves in some sort of tomb. The same approach is applied in the space dedicated to child victims.

While all the men were shot, women were placed in concentration camps, the Lidice children were transported to Polish Chelmno and here exterminated by exhaust fumes in specially adapted trucks. Of the total number of 105, only seventeen were saved. The exhibition, apart from several photographs, is dedicated to their last words, captured on postcards that were sent from Poland a day before the execution.

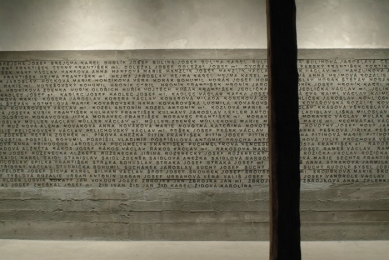

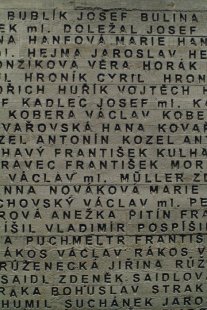

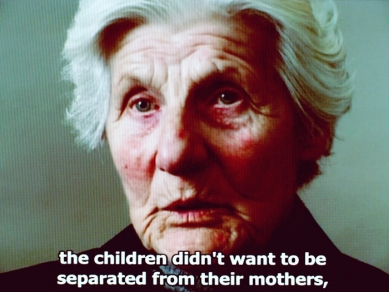

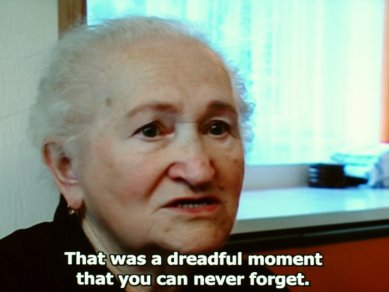

Just near the exit of the museum, behind a solemn wall engraved with the names of all the victims of Lidice, which forms a counterpoint to the immateriality of the images, there are several photographs focusing on the fate of the memorial itself. Here, for the first time, color appears, and from the modern flat screen, survivors and elderly women speak to us, like an intervention of presence confirming the profundity and subtle fragility of the images of a cruel past.

Client: Memorial Lidice - contributory organization of the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic

Historical script: Dr. E. Stehlík, Mgr. M. Burian, and for the MK ČR Dr. J. Žalman - VHÚ

Multivision: Pavel Štingl, editing: Pavel Hudec

However, it is questionable to what extent such an approach is even possible. Since the museum's exhibition is primarily based on period photographs, archival film material, and admittedly newly shot material, even the projection in the circular entrance chamber is a sort of interpretation of history, placing the Lidice tragedy within the context of the global political situation. The projection takes place simultaneously on three screens placed next to each other, where images of global events are combined with pictures of everyday life, sometimes arranged together in overly conventional ways. Work in the fields and in factories, the First Republic with its icon T. G. Masaryk, the crash on the New York Stock Exchange, Hitler's rise to power, the occupation of Czechoslovakia, war... until the collage culminates in the very comparison of Lidice with the ground. The combination of the three screens, a technique once invented by Abel Gance for his historical film "Napoleon," protects the projection from superficial interpretation, forcing the viewer to jump their gaze from screen to screen, collaborating in connecting individual scenes, and preventing nostalgic repose in their age. Through the rapid cuts occurring between the screens, along with the aggressive sound component of war and the darkly rumbling crowds, considerable expressive impact is achieved in the eight-minute film. After we "take in" the final panoramic view of the burned Lidice, we can enter the museum's exhibition itself.

We find ourselves in a dimly lit rectangular hall with rough plastered walls showing traces of circular smoothing movements. The technical equipment of the room, including the air conditioning and data projectors, is equally transparently acknowledged.

The room is divided by monolithic concrete panels, creating various nooks, loops, and chambers that irregularly run along the walls. The imaginary, conceptual, rather than geometric center of the room is formed by the gates of the former Lidice church, which fortuitously survived, and the large concrete slab behind them onto which a photograph of the altar is projected. It serves as a conceptual center representing a return to something that was overturned and which, as the exhibition's authors likely believe, is undeniable. It creates a virtual space of a temple, raised above the relics of preserved objects, around which both ordinary and horrifying scenes unfold, perhaps serving as a manifestation of the desire for the restoration of a brutally disrupted order.

As we walk along the walls and visit individual chambers, we chronologically traverse the history suggested by the initial image, with its symbolic representation also being the gas chamber. This history is composed of further edited short films, each dedicated to a specific phase of the development of the causes of the massacre's tragedy.

However, the arrangement of the exhibition also has a different meaning than mere chronology. Apart from several solemnly displayed items that survived from the village and escaped destruction, nearly the entire exhibition consists of images, both static and moving, projected onto concrete slabs and thus by light. It is a kind of fragility, immateriality, and unreality of the projected photograph, which is supported by concrete blocks, a process not unlike the ancient Greek mystical principle of the emanation of divine light through darkness and its permeation of matter in the act of creation. Here too, light gives rise to a flickering of images on the surface of the concrete, which, however, simultaneously destroys the images, as traces of the wooden boards in which the slabs were cast emerge to the surface, along with various blemishes and pores of the material. The idea, the memory, the act of reverence—all require matter for their creation, unfolding on its surface, while also remaining vulnerable, immaterial, threatened by extinction, non-existence. Despite the endless repetition of loops of films reminiscent of the obsessive fixation of "tormenting memories," we sense that it only takes turning off the data projectors for bare, brutal, and cold concrete to remain. The act of remembering, of thinking, requires effort; the spiritualizing of matter is thus not merely a mechanical affair.

However, it is primarily the content of the images that is oppressive. As we walk along the walls, we first encounter small snapshots that have survived from the village. Images of residents, men, women, and children, captured on solid material, all in such small formats that voyeuristic access to the matter is prevented, compelling the visitor to approach the concrete wall and extract the image from it with their attention. The only exception is a large-format photograph of students in a classroom. Here I cannot refrain from a small criticism. While it is indeed preserved material and a selection from it, trivial images such as ducks on the water or a dog with glasses sitting in a chair belong to the traces of everyday life in Lidice; however, within the entire exhibition based on the necessity of increasing the attention paid to the images, they seem somewhat out of place. The images of children, which appear in several sectors, are also unnecessarily overused, as it seems to me at least, introducing unnecessary sentiment even where the authors otherwise managed to avoid it.

Following are film images and collages of Heydrich's aggressive proclamations threatening to erase the Slavic race from the surface of the usurped land, wartime scenes, Czechoslovak units in England from which the assassins were recruited, the assassination of Heydrich itself, and his subsequent burial in Berlin along with the dead paratroopers.

The day after Heydrich's funeral, the Lidice massacre took place. We stand over a concrete embankment, in which bodies of shot men are projected. The blurriness of the photograph does not allow us to discern the details of the image, yet even here, we are prevented from disturbing the dead with our curiosity. As we approach the image, the projector placed behind us casts our own shadow onto the surface. The image disappears behind its outlines, and we ourselves, with our own bodies, become part of the realm of the dead, the valley of shadows. It is an extremely disturbing feeling, a phenomenon that haunts us throughout the exhibition and contributes to the intensification of a stifling atmosphere.

The next part of the exhibition is dedicated to familiarizing oneself with the individuality of the murdered, as far as the view on the light imprint of a human face in photochemical material allows and distinguishes it from the mass of the common grave. Small, period portrait photographs running in a thin line along the wall, faces of the 199 executed with attached names. In these places, the walls are equipped with a low ceiling, as if we were finding ourselves in some sort of tomb. The same approach is applied in the space dedicated to child victims.

While all the men were shot, women were placed in concentration camps, the Lidice children were transported to Polish Chelmno and here exterminated by exhaust fumes in specially adapted trucks. Of the total number of 105, only seventeen were saved. The exhibition, apart from several photographs, is dedicated to their last words, captured on postcards that were sent from Poland a day before the execution.

Just near the exit of the museum, behind a solemn wall engraved with the names of all the victims of Lidice, which forms a counterpoint to the immateriality of the images, there are several photographs focusing on the fate of the memorial itself. Here, for the first time, color appears, and from the modern flat screen, survivors and elderly women speak to us, like an intervention of presence confirming the profundity and subtle fragility of the images of a cruel past.

Client: Memorial Lidice - contributory organization of the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic

Historical script: Dr. E. Stehlík, Mgr. M. Burian, and for the MK ČR Dr. J. Žalman - VHÚ

Multivision: Pavel Štingl, editing: Pavel Hudec

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

3 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

klobouk dolů

sauer

16.11.07 02:19

doporucuju

joey

14.04.08 12:05

silný zážitek

Katka Jarošová

05.09.09 12:32

show all comments