Synagogue annex Community Centre

Nieuwe synagoge

Is true architecture not the design of emptiness; the space between walls, floors and ceilings, between the materials themselves? Does the opposite not lead inevitably to flamboyance and ostentation, to something that aspires to be more than it actually is?

The widespread existence of the Jewish community and the unstable relationship between Judaism and other religions have hindered the evolution of a recognised architectural style. This contrasts with the development of a very confident Jewish identity.

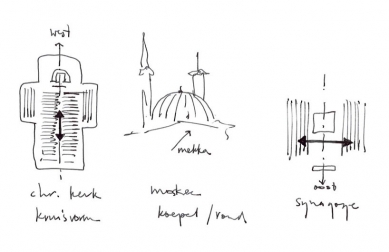

Ceremonial traditions and rituals present few recognisable reference points in a synagogue’s physical expression. And while the identity of a church or a mosque is carved in stone, it is usually conspicuous in its absence with regard to synagogues. The positioning of the benches opposite each other and parallel to the axis between the Bimah (preaching seat) and the Ark (depository for the Torah rolls), and the use of bright daylight are the most important starting points for the design process. Moreover, the emptiness, visualisation of the enigmatic Jewish identity (nesjomme) with its subtle and complex character, plays a significant role.

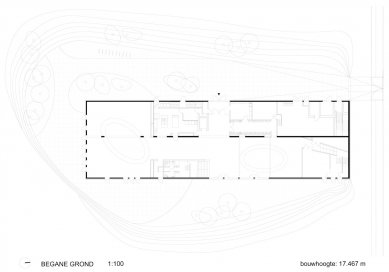

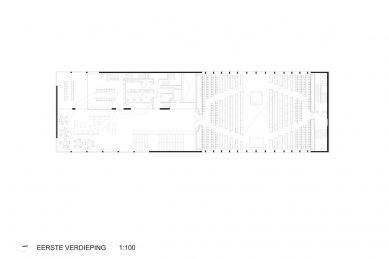

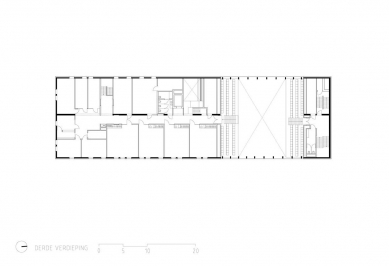

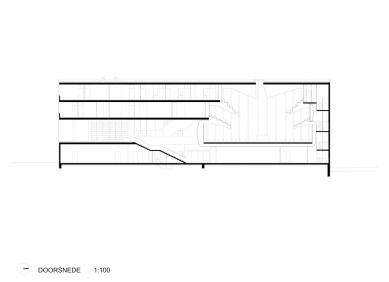

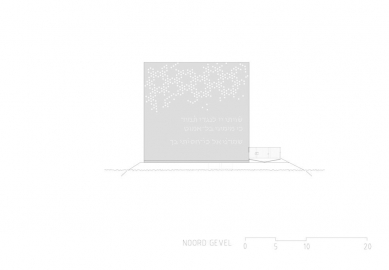

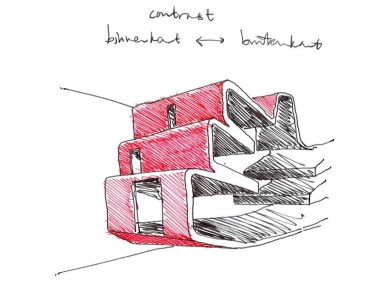

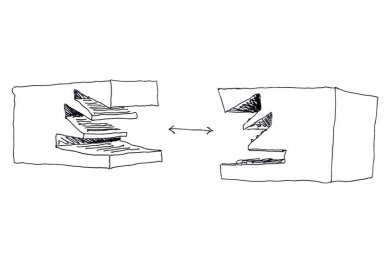

In this project, a neutral rectilinear ‘volume’ is formed through the optimally efficient use of both site and budget. The hollowing out of this mass, to form the ‘emptiness’ of the great Sjoel, lends the building its identity. The Sjoel consists of a large central space with low extensions on either side under two-tiered balconies. The arrangement of these side spaces, the four balconies above them and the central void above the Bimah suggest the Menora, the seven-armed chandelier. The Menora (the light) symbolises the burning bush discovered by Moses on Mount Sinai and is the oldest and most important symbol of Judaism. In the beginning God created light. Without light there is no life.

The widespread existence of the Jewish community and the unstable relationship between Judaism and other religions have hindered the evolution of a recognised architectural style. This contrasts with the development of a very confident Jewish identity.

Ceremonial traditions and rituals present few recognisable reference points in a synagogue’s physical expression. And while the identity of a church or a mosque is carved in stone, it is usually conspicuous in its absence with regard to synagogues. The positioning of the benches opposite each other and parallel to the axis between the Bimah (preaching seat) and the Ark (depository for the Torah rolls), and the use of bright daylight are the most important starting points for the design process. Moreover, the emptiness, visualisation of the enigmatic Jewish identity (nesjomme) with its subtle and complex character, plays a significant role.

In this project, a neutral rectilinear ‘volume’ is formed through the optimally efficient use of both site and budget. The hollowing out of this mass, to form the ‘emptiness’ of the great Sjoel, lends the building its identity. The Sjoel consists of a large central space with low extensions on either side under two-tiered balconies. The arrangement of these side spaces, the four balconies above them and the central void above the Bimah suggest the Menora, the seven-armed chandelier. The Menora (the light) symbolises the burning bush discovered by Moses on Mount Sinai and is the oldest and most important symbol of Judaism. In the beginning God created light. Without light there is no life.

SeARCH

0 comments

add comment