World metropolises cannot avoid grand architectural gestures. In the case of the city above the Seine, it suffices to recall Eugène Haussmann or

Gustave Eiffel. It is also traditional for French presidents to etch their names into the memory of the nation with bold construction projects that will then bear their names. Alternately, they manage to combine successes with architectural scandals of gigantic proportions. While Georges Pompidou launched a successful career for the later two Pritzker Prize winners with his

cultural center, his later successor, François Mitterrand, mostly aimed off the mark of architectural taste. The new ethnographic museum is the child of Jacques Chirac and can boldly be classified among the projects that transformed the image of the entire city.

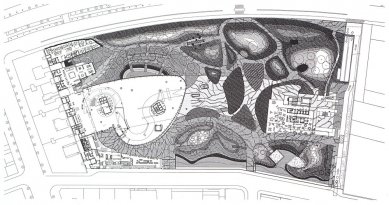

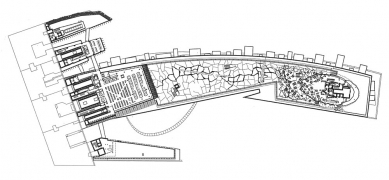

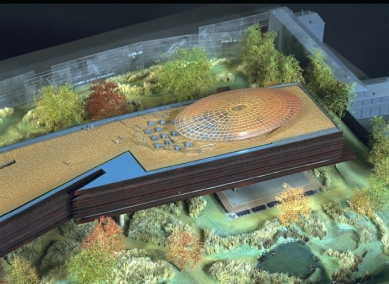

Naysayers claim that greenery can remedy most of the architect's mistakes. However, I don't know what they would say about the new museum located on the left bank of the Seine in the shadow of the famous Eiffel Tower. Garden architect Gilles Clémens collaborated with vertical garden specialist Patrick Blanc to create a living work that is not just an equal partner to the building, but Nouvel's project simply cannot do without it. A year after completion, the nineteen-acre garden is in full bloom, and its greenery is diligently working to absorb the structure. Facing the river, it forms a facade of a unique 800 m² vertical garden covered with more than 15,000 plants. Greenery constitutes more than 70% of the total area of the site. Whenever we returned to the museum during our stay, the sky would overcast and it would start to rain. We slowly began to believe that Clémens and Blanc had created their own weather on this small piece of Paris, complete with a tropical microclimate.

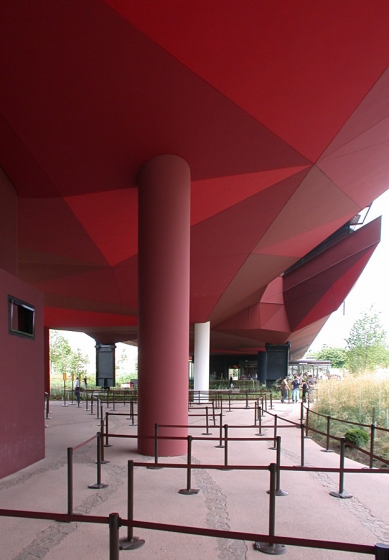

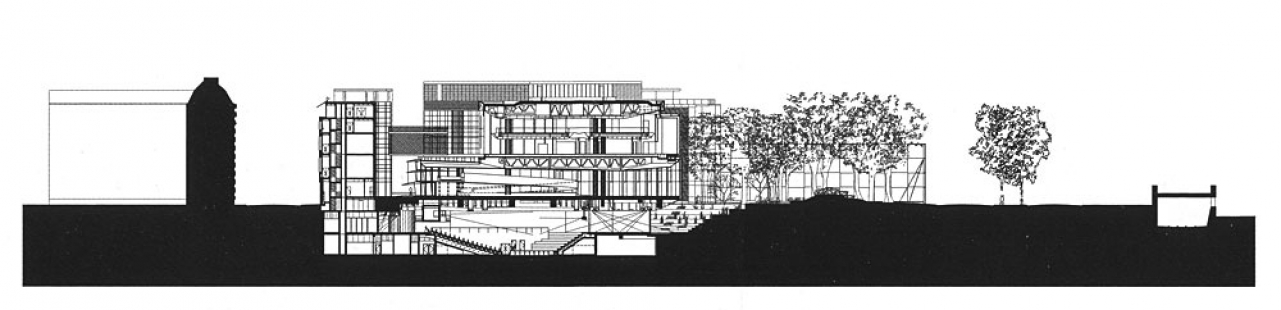

The Musée du Quai Branly presents itself enigmatically. Its form is wild, eccentric, and leaves no one indifferent. Just as the museum is a heterogeneous mix of volumes, opinions about the building are also very mixed. Nouvel did not want to use traditional Western building methods for the museum of primitive cultures. At the same time, he did not want to create a caricature of indigenous architecture. Moreover, the museum had to deal with the legacy of Baron Haussmann. A number of large apartment buildings from the 19th century with a clear construction order and monotonous facades remained on the western edge of the site. Nouvel's intention was to break away from entrenched barriers and create an environment capable of embracing the art of various cultures from four continents. The museum consists of four parts rising from Haussmann's tenement houses. Each part has its own architectural expression and a different purpose: the smaller serves administration and artistic studios while the larger is for exhibitions.

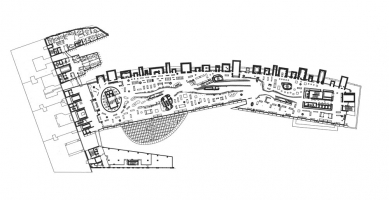

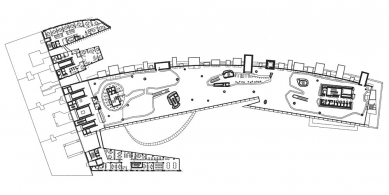

In the 19,000 m² garden, the mass of the main exhibition hall is shrouded among mature trees, which is placed into a 220-meter-long steel superstructure. This 3,400-ton structure is elevated 10 meters above the ground by 26 massive columns. Inside, at many different height levels, there are permanent exhibitions, temporary exhibitions, scientific workspaces, media libraries, classrooms, and auditoriums. For the needs of the museum, there are three additional galleries, two of which (800 m² on the west, 600 m² on the east side) serve thematically focused exhibitions, and one multimedia gallery, where visitors can listen to anthropological information. At the eastern end of the museum, there is a restaurant with its own entrance, and its main feature is a giant glass roof. From the restaurant built on an elevated platform above the museum, one can descend to an open terrace.

A long and high glass wall decorated with silkscreen prints filters traffic noise similar to Nouvel's ten-year-old project

Fondation Cartier. However, a far more characteristic feature of the museum has become the boxes hanging on the northern facade. These variously sized colorful "outgrowths" serve as study rooms and simultaneously exhibition spaces for particularly valuable exhibits. Every visitor must pass through lush vegetation before entering the museum and buy a ticket in the open space beneath the main hall. From the entrance hall strategically located at the center of the buildings, paths lead to all parts of the museum. The space is dominated by a glass cylinder of the depot with archived (and yet exhibited) objects. Around the cylinder, a wide white ramp slowly winds upward to the main exhibition hall. To make the journey more pleasant, a multimedia show unfolds on the floor of the ramp. From the dim corridor, one enters the dimness of the main hall. The authors of the exhibition worked with minimal light. Organically shaped "boulders" covered with artificial skin sharply contrast with the large glass display cases. In the dark environment, the large glass panels seem to disappear. Nevertheless, you sense their existence and do not bump into them. Only the softly lit exhibits in the space clearly dominate. Thanks to the glass display cases, you can view objects from multiple sides and observe what is happening behind them in other planes. The externally uncompromising architecture remains inside due to the prevailing dimness in the background and allows the exhibited objects to stand out. In the main hall, you have absolute freedom of movement. There is no established tour route. Only the differently colored floors tell you from which continent the exhibited objects were brought.

The contemporary architectural scene in Paris is playful and pointed. The era when buildings only had to serve their function well is irrevocably gone. The Musée du Quai Branly is perhaps the greatest example of this.

Competition Proposals

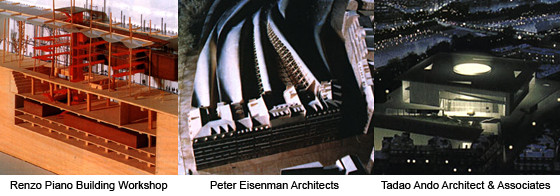

President Chirac proposed to build the Musée d'Arts et des Civilisations (MAC) on the banks of the Seine in 1996. The new museum for 150 million Euros was to merge with the existing collections of the Musée des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie. To ensure profitability, this cultural project was also to include a hotel complex with a restaurant. The author was to be decided by a rapid international architectural competition with completion planned for 2002.

|

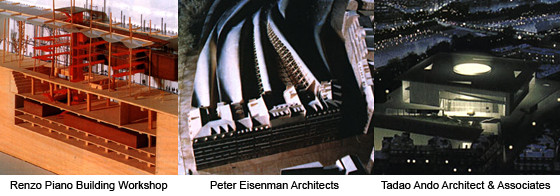

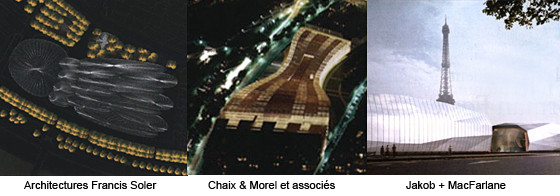

The quick competition eventually turned into a three-round marathon. In July 1999, the jury selected 15 prominent architects, including Rem Koolhaas, Norman Foster, or Tadao Ando. At the beginning of December 1999, the jury reconvened and awarded projects to Jean Nouvel, Peter Eisenman, and Renzo Piano. The final winner was selected by President Jacques Chirac and commissioned for the museum for one billion French francs. At the end of 1999, everyone still believed that the museum would be completed by 2004. Ultimately, the opening of the museum was delayed by two years, and costs soared from the originally planned 167 million Euros to a final 235 million.