Church and Monastery of St. Hallvard

St. Hallvard Church and Monastery

Catholic Church and Monastery of Saint Hallvard is located on the rocky hill of Enerhaugen in the eastern part of central Oslo. The surrounding neighborhood is densely populated and is one of the most ethnically and religiously diverse in the city. However, the immediate vicinity does not consist of compact urban development but rather a collection of high residential blocks built at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s. Saint Hallvard is a Norwegian saint, the patron of Oslo – his stylized figure can still be seen on symbols associated with the city, including, for example, canal covers. The dedication follows the nearby medieval Cathedral of Saint Hallvard, of which only ruins remain today. The new monastery was built for the Franciscans, who used it until 2008, since when the operation of the parish has been managed by lay priests. Saint Hallvard is the largest Catholic parish in Norway – at the time of the consecration of the church on May 15, 1966, it had 1,000 parishioners, today there are over 12,000, primarily consisting of various immigrants from the surrounding neighborhoods of Grønland and Grünerløkka.

In traditionally Protestant Norway, the Catholic church is an exception, and so is its appearance.

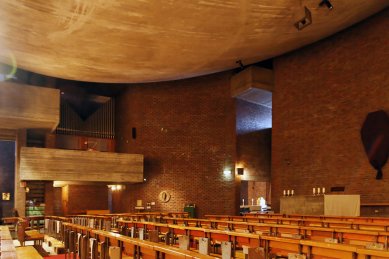

Lund and Slaatto were among the most successful and also the most productive architects in Norway from the 1950s to the 1980s. With this building, they came closest to brutalism in their work: they chose bricks and rough concrete as materials, complemented by glass. The church is designed on the basis of a circle inscribed in a square. The architects utilized this ground plan scheme in their next building, the student house Chateau Neuf in Oslo. In the case of the church, however, the shape of the circle primarily corresponds to the ceiling, whose form dominates the interior of the building. The concrete ceiling has a concave shape, making it significantly sag above the church nave. This, of course, creates a strong sensory effect and carries symbolism: it emphasizes the center of the central space of the church nave and the imaginary vertical axis that passes through it. The interior is deliberately very dark, and light enters here only through narrow slits in addition to low doors. The walls made of rough materials have a strong haptic effect, and embedded in them are also light fixtures or, for example, a small fragment of Gothic carved stone from the former cathedral. The building immediately attracted great attention upon completion, earning several architectural awards. It was also addressed by the most famous Norwegian architect and theorist Christian Norberg-Schulz, whose text follows here. In 1993, the external shape of the entire building became somewhat complicated when two extensions with a semicircular floor plan were added. They house the offices of the charity and the parish room.

Barely any building from the 1960s has received such interest and recognition as the Church and Monastery of Saint Hallvard on the hill of Enerhaugen. The basic theme of the project is remarkably simple; the circular space of the church is located in the center of a square block. From the outside, the block appears as a closed mass that possesses extraordinary strength despite its modest dimensions. The entrance to the church is through a narrow slit that emphasizes both the effect of the block and the enveloping circular form of the interior. It might seem natural to imagine some dramatic church in contrast to the surrounding dull, loosely arranged residential blocks dominating the hill. Today, it is also common to embellish churches with steep roofs and rising shells – architects hope to achieve a 'sacred' effect that way. Lund's and Slaatto’s building reminds us that the sacred is something deeper. Instead of seeking solutions through grand gestures, they created a strong form. This corresponds to the monastic principle of separation or even expresses an 'unreachable' character. Nevertheless, it is mainly the church space itself that demands our attention. The circular space particularly well satisfies the human need for a fixed point; at the same time, it expresses a sense of community through the act of gathering. In Saint Hallvard, these fundamental qualities come alive again; the masonry walls gather and unify, while cleverly planned asymmetrical elements reflect the contrasting complexity of modern life. It is especially the pronounced ceiling that gives the space its most notable characteristic. This peculiar 'anti-dome' is both daunting and soothing, just as Heaven is simultaneously always new and known. In 1966, Kjell Lund gave a lecture at the Oslo Architects’ Association entitled "Architecture and Identity," in which he stated:

“Throughout all times, man has created images to see himself and to be what he sees. Through images, he sought identity (…). As architects, we know all the elements that establish the architectural language of images – yet none of us know them well enough (...). The crucial point for us is that the structure or environment is arranged in such a way that stimulates our psychological needs (…). Norwegian architects have a reasonably developed social awareness. We are concerned with many areas and rightly demand that our views be respected. But when we express our thoughts through architecture – its own language, we are still powerless (...).”

In Saint Hallvard, Lund and Slaatto demonstrated that they are masters of architectural expression and, through its use, created a true place with identity.

Literature

– Lund & Slaatto. St. Hallvard kirke og kloster, text by Christian Norberg-Schulz, Kjell Lund, P. Johan C. H. Castricum OFM, P. Ronald Hölscher OFM, Arfo, Oslo 1997.

– Christian Norberg-Schulz, Modern Norwegian Architecture, Oslo 1986.

In traditionally Protestant Norway, the Catholic church is an exception, and so is its appearance.

Lund and Slaatto were among the most successful and also the most productive architects in Norway from the 1950s to the 1980s. With this building, they came closest to brutalism in their work: they chose bricks and rough concrete as materials, complemented by glass. The church is designed on the basis of a circle inscribed in a square. The architects utilized this ground plan scheme in their next building, the student house Chateau Neuf in Oslo. In the case of the church, however, the shape of the circle primarily corresponds to the ceiling, whose form dominates the interior of the building. The concrete ceiling has a concave shape, making it significantly sag above the church nave. This, of course, creates a strong sensory effect and carries symbolism: it emphasizes the center of the central space of the church nave and the imaginary vertical axis that passes through it. The interior is deliberately very dark, and light enters here only through narrow slits in addition to low doors. The walls made of rough materials have a strong haptic effect, and embedded in them are also light fixtures or, for example, a small fragment of Gothic carved stone from the former cathedral. The building immediately attracted great attention upon completion, earning several architectural awards. It was also addressed by the most famous Norwegian architect and theorist Christian Norberg-Schulz, whose text follows here. In 1993, the external shape of the entire building became somewhat complicated when two extensions with a semicircular floor plan were added. They house the offices of the charity and the parish room.

Barely any building from the 1960s has received such interest and recognition as the Church and Monastery of Saint Hallvard on the hill of Enerhaugen. The basic theme of the project is remarkably simple; the circular space of the church is located in the center of a square block. From the outside, the block appears as a closed mass that possesses extraordinary strength despite its modest dimensions. The entrance to the church is through a narrow slit that emphasizes both the effect of the block and the enveloping circular form of the interior. It might seem natural to imagine some dramatic church in contrast to the surrounding dull, loosely arranged residential blocks dominating the hill. Today, it is also common to embellish churches with steep roofs and rising shells – architects hope to achieve a 'sacred' effect that way. Lund's and Slaatto’s building reminds us that the sacred is something deeper. Instead of seeking solutions through grand gestures, they created a strong form. This corresponds to the monastic principle of separation or even expresses an 'unreachable' character. Nevertheless, it is mainly the church space itself that demands our attention. The circular space particularly well satisfies the human need for a fixed point; at the same time, it expresses a sense of community through the act of gathering. In Saint Hallvard, these fundamental qualities come alive again; the masonry walls gather and unify, while cleverly planned asymmetrical elements reflect the contrasting complexity of modern life. It is especially the pronounced ceiling that gives the space its most notable characteristic. This peculiar 'anti-dome' is both daunting and soothing, just as Heaven is simultaneously always new and known. In 1966, Kjell Lund gave a lecture at the Oslo Architects’ Association entitled "Architecture and Identity," in which he stated:

“Throughout all times, man has created images to see himself and to be what he sees. Through images, he sought identity (…). As architects, we know all the elements that establish the architectural language of images – yet none of us know them well enough (...). The crucial point for us is that the structure or environment is arranged in such a way that stimulates our psychological needs (…). Norwegian architects have a reasonably developed social awareness. We are concerned with many areas and rightly demand that our views be respected. But when we express our thoughts through architecture – its own language, we are still powerless (...).”

In Saint Hallvard, Lund and Slaatto demonstrated that they are masters of architectural expression and, through its use, created a true place with identity.

Source: Ch. Norberg-Schulz, Modern Norwegian Architecture, pp. 121-123

Text author, translation of the excerpt and photographs: Ondřej Hojda

Text author, translation of the excerpt and photographs: Ondřej Hojda

Literature

– Lund & Slaatto. St. Hallvard kirke og kloster, text by Christian Norberg-Schulz, Kjell Lund, P. Johan C. H. Castricum OFM, P. Ronald Hölscher OFM, Arfo, Oslo 1997.

– Christian Norberg-Schulz, Modern Norwegian Architecture, Oslo 1986.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment