Kiasma

Museum of Contemporary Finnish Art

Many organizations have been striving for over forty years to establish a Museum of Contemporary Finnish Art. In 1990, it was finally established as part of the Finnish National Gallery, and for the next eight years, it was forced to survive in small and inadequate spaces at Atenea. In 1993, the city of Helsinki announced a public competition, which received over 516 proposals (open only to Nordic, Baltic, and invited world-renowned architects such as Coop Himmelb(l)au, Álvaro Siza, or Kazuo Shinohara), which was ultimately won by Steven Holl with his project titled “Chiasma - intertwining the mass of the building with the geometry of the city and landscape.”

For the future building, Töölönlahti Bay was chosen, located in the city center near Aalto's Finlandia Hall, Eliel Saarinen's train station, and the statue of Field Marshal C.G. Emil Mannerheim (the greatest hero of the civil war). Paradoxically, the smallest of these three objects posed the biggest obstacle (attacks from the press, city council members, and the public).

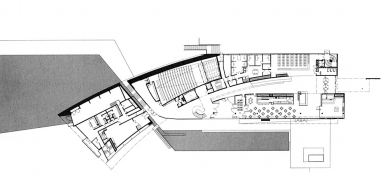

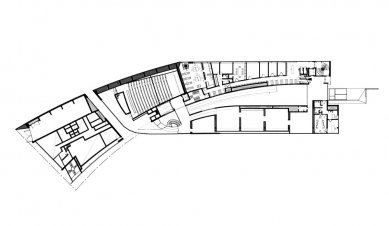

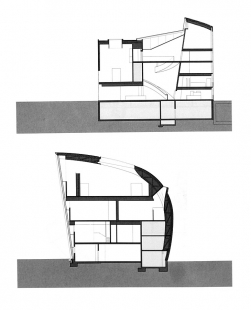

The double-curved intertwiner was made of zinc, a pile of steel, glass, and shiny black concrete. The issue of adequately lighting 25 exhibition halls across five floors posed no difficulties for the Master, who was able to create a cooling and refreshing atmosphere for visitors inside with “his” light. Conversely, from the outside, the building appears as a radiant worm in the almost always cloudy Helsinki. The entrance hall is synonymous with the original idea, serving as the main communication element and the least photogenic aspect of the interior. Kiasma was the first from the project to remodel the entire Töölönlahti Bay, and other promising buildings are beginning to emerge in its vicinity.

Petr Šmídek, 2001

Personal feelings – the museum does not appear as monumental from the outside as it does in most photos. If a visitor does not know the story of the intertwining that the architect encoded into the museum, the building may seem like a giant sculpture twisting between a glass administrative building and a busy thoroughfare. The ground floor of the museum dominates social life and commerce. Although half of the indoor spaces are taken up by ramps, staircases, corridors, and other communications, there is still enough room for galleries. I visited the museum twice, and each time the space won over the exhibited artifacts. The galleries are not particularly suitable for displaying works. Nothing can be installed on the slanted walls, and the skylights are more for show or artistic effect. The museum is a place for walking, meeting, and observing other visitors rather than for the art itself. Movement is the most important means of perceiving the museum's space (its central area).

Holl’s artistic ambitions did not stop at forming the outer shell and arranging the interior walls. A visit to the restrooms here offers the same artistic experience as in the upper galleries (meant in a positive spirit). The partition walls, copper faucets, sinks, handles, and covers bear a clear signature of Holl. My damaged spine won't settle for just any chair. I found it incredibly pleasant to sit on those emerald-colored pieces behind the copper tables in Kiasma's café. It’s a pity I am not a few years younger. The wire children's chairs here have translucent wings. The interior furnishings, although seemingly cheap, carry the spirit of the artist.

I have until now insisted that Holl’s European realizations lag significantly behind his American ones. After visiting Kiasma, I will have to reassess this opinion. Just as I brought the strongest experience from last year’s visit to Portugal from the Casa da Música by the Dutch OMA, one of the highlights from this year’s trip to Northern Europe was the construction by an outside author.