Parkrand Housing Building

|

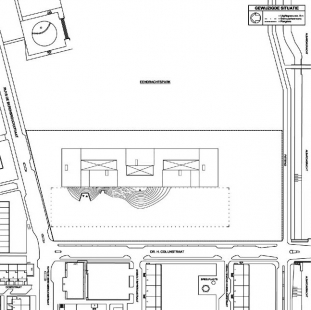

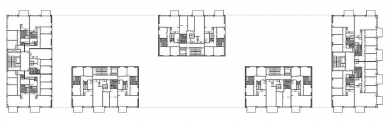

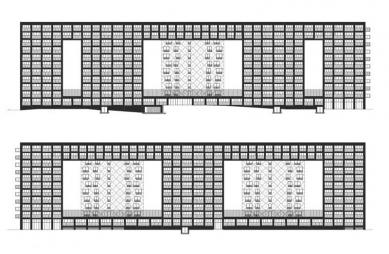

The complex is positioned parallel to the edge of the Eendrachts Park on a site previously occupied by three hook-shaped housing blocks. (Designating the new complex as an architectural icon also seems to be a way of justifying the demolition of 174 homes on the site.) Parkrand is a substantial building – 135 metres long, 34 metres high, 223 dwellings. According to the 1998 urban plan, the building should strengthen the relation between Neighbourhood 9 and the Eendrachts Park. The question is whether this has been achieved. Parkrand consists of a plinth on which stand five towers connected together at the top. The plinth means that the relation between the neighbourhood and the park is purely visual, the trees of the park can be seen through the towers.

MVRDV describes Parkrand as a country house. The complex has a front door onto Dr. Colijnstraat, and a rear entrance directly from the park. A semi-public hall with letterboxes and a caretaker provides access to the private quarters, the ‘corridor’ from where the different towers containing the apartments are accessed. The dwellings, from 87 to 132 m2 in area, are bright thanks to the floor-high windows and doors, and an outdoor space in the form of a big balcony – something of a rarity these days. Non-standard apartments are located in the bridge section (11th and 12th floors). The revealed structure adds an extra dimension to these apartments.

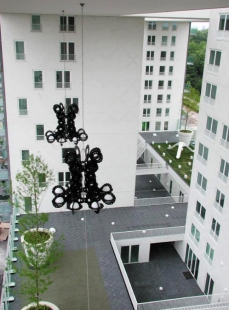

The complex contains three so-called outdoor rooms. Richard Hutten designed a children’s room, a living room and a dining room. These are spaces where residents can rest between the private domain of the home and the public park. The domestic association is reinforced by the materials deployed. The façades to the street and park are faced with dark prefab concrete panels, while the private spaces are enclosed by façades of glazed white bricks. Smoothly and ‘irregularly’ fired bricks add a pattern to these façades that, just like relief wallpaper, is only visible with a certain incidence of light. The big openings and the visibility of the interior elements – the lights and the white ‘wallpaper’ – recall the half-demolished housing blocks scattered throughout the western garden suburbs. The monument like complex will be a reminder of the demolition rage that swept across the garden suburbs long after the transformation process has been completed.

Marina van den Bergen, June 2007

0 comments

add comment