Bonnefanten Museum

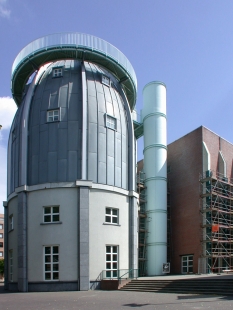

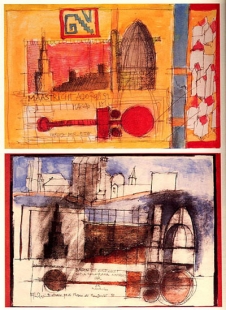

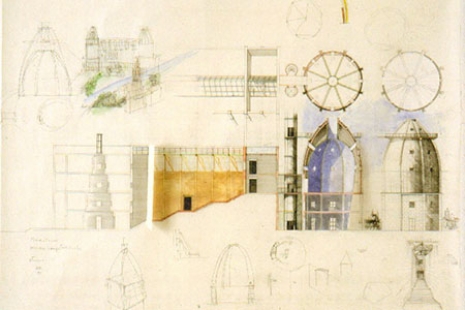

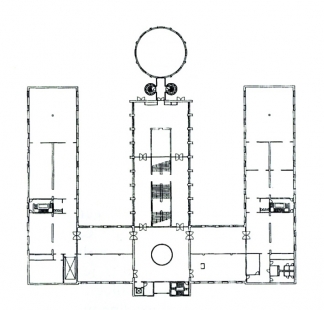

The museum was founded by the Dutch province of Limburg in 1884 as a historical and archaeological museum. The name of the museum, Bonnefanten, is derived from the French 'bons enfants' ('good children'), which was a nickname of the former monastery where the museum was located from 1951 to 1978. In 1995, the museum moved to its current address on the opposite bank of the historic center of Maastricht, to the former site of the ceramic factory 'Sphinx/Société Céramique', which was replaced in the early 1990s by an urban project by Jo Coenen. The new museum building on the banks of the Maas was designed by Italian architect Aldo Rossi, who created a strictly symmetrical layout with a floor plan shaped like the letter E. The entire complex is topped with a 28-meter-high central tower resembling a space shuttle. Rossi's design can also evoke a coffee maker, a bullet casing, or an astronomical observatory. The interpretation remains with the visitors, but everyone remembers this metal landmark deeply. It serves as a subconsciously familiar symbol connecting the past with the present. Rossi's postmodern work can indeed be both very austere and whimsical, classical and modern. The museum, which opened in March 1995, represents one of the last works of the significant Italian “painting poet who became an architect”. Since 1999, the originally historical and archaeological museum has focused exclusively on exhibiting art.

The Maastricht Museum is situated on the banks of the river Maas (the Dutch name of the Meuse) in the suburb which has been linked to the city since ancient times by the Roman bridge from which the city gets its name (Masa tractum).

The museum is composed of three parts: the central building is flanked by a cylindrical body covered by a high dome; this is crowned by a belvedere from which the river and the city on the opposite bank can be admired.

In the building, there is a long staircase covered in wood; this and other features are the very substance of this architecture which reminds us of the seafaring tradition of the Dutch cities as well as of the great river which crosses Europe and flows through Maastricht.

How difficult and indescribable are both architecture and memory! For this reason, I would like to attempt a personal and necessarily incomplete description of my attempt to see the museum in a light that avoids those problems which, because of the word itself, seem to have pathological associations rather than advanced ones. Perhaps I will end up by demonstrating that the museum, like the histories of all of us, like every vice and virtue and everything that has to the limited dimensions of a marble slab which only the foolish minds of the Enlightenment wished to measure in meters and centimeters. This museum is an attempt to reject this foolishness.

The first room which the visitor encounters is the entrance hall; it has the distinctive form of a telescope. This is a typical example of a lichtraum, the precedent for Zürich University; moreover, this form is not typically northern, but represents the most important contact between Spanish architecture and the colonies. Thus, there is a direct link between Vermeer and Zurbarán. The light of the houses in the monasteries preserves in the monument the ephemeral nature of both daily life and the religious one. This room, which fills the height of the building, is decorated with an aquamarine material; the light and color appear to cause its very substance to disintegrate.

From the entrance hall, the visitor proceeds directly to the living heart of the museum, which is entered with fear and trepidation. How difficult it is, almost impossible I daresay, to define this essence! Is the museum a collection of mementoes of life or is it itself part of our lives? My architecture leaves an open verdict in this regard. Nonetheless, the substance of the museum is the origin and end of our cultural decadence.

Now let us climb the stairs. It is hardly worth mentioning that this steep and awkward staircase. In the ancient Dutch tradition, is linked to the world, knowing only too well that beyond geometry there is only a shipwreck. And drawing a parallel between the two great seafaring nations I would like to quote the words of the great Portuguese poet: “Portugal is the country where the land ends and the sea begins.” And, in fact, do we not confound the buildings of Macao, Singapore, and northern Japan with those of these countries that are so thoroughly European and yet so exotic?

At the top of the stairs, among energetic young people and breathless senior citizens, we may admire the skilful display of the exhibits by the director. Far from being a celestial director, he is a true curator who is sensitive to the different emotional levels of light and beauty. Never in the history of architecture have larger works been seen which did not correspond to a sort of alliance between the patron and the artist, the bureaucrat and the engineer.

I will not carry on with the description, even if the basic tenet of Latin literature, as in the case of Virgil, was description rather than invention. But I cannot dwell upon the sorrows of Dido which have already been described to excess by the great Racine. Rather let us consider a number of the features which impress visitors, even the hasty ones, in the museum as a whole. Were you to ask the simplest person in Europe, there would only be one answer: the dome.

There are two main reasons for the magnificence of the dome: the first is its link with the architectural tradition of the classical world right up to the nineteenth-century Turinese architect Alessandro Antonelli; the second is that between river and sea it boldly signals the lie of the land in that country.

But now, just as if we were standing on the belvedere, we can view the museum as a whole, perhaps a lost whole that we only recognize thanks to those fragments of our lives which are also fragments of art and Europe of bygone days.

The Maastricht Museum is situated on the banks of the river Maas (the Dutch name of the Meuse) in the suburb which has been linked to the city since ancient times by the Roman bridge from which the city gets its name (Masa tractum).

The museum is composed of three parts: the central building is flanked by a cylindrical body covered by a high dome; this is crowned by a belvedere from which the river and the city on the opposite bank can be admired.

In the building, there is a long staircase covered in wood; this and other features are the very substance of this architecture which reminds us of the seafaring tradition of the Dutch cities as well as of the great river which crosses Europe and flows through Maastricht.

How difficult and indescribable are both architecture and memory! For this reason, I would like to attempt a personal and necessarily incomplete description of my attempt to see the museum in a light that avoids those problems which, because of the word itself, seem to have pathological associations rather than advanced ones. Perhaps I will end up by demonstrating that the museum, like the histories of all of us, like every vice and virtue and everything that has to the limited dimensions of a marble slab which only the foolish minds of the Enlightenment wished to measure in meters and centimeters. This museum is an attempt to reject this foolishness.

The first room which the visitor encounters is the entrance hall; it has the distinctive form of a telescope. This is a typical example of a lichtraum, the precedent for Zürich University; moreover, this form is not typically northern, but represents the most important contact between Spanish architecture and the colonies. Thus, there is a direct link between Vermeer and Zurbarán. The light of the houses in the monasteries preserves in the monument the ephemeral nature of both daily life and the religious one. This room, which fills the height of the building, is decorated with an aquamarine material; the light and color appear to cause its very substance to disintegrate.

From the entrance hall, the visitor proceeds directly to the living heart of the museum, which is entered with fear and trepidation. How difficult it is, almost impossible I daresay, to define this essence! Is the museum a collection of mementoes of life or is it itself part of our lives? My architecture leaves an open verdict in this regard. Nonetheless, the substance of the museum is the origin and end of our cultural decadence.

Now let us climb the stairs. It is hardly worth mentioning that this steep and awkward staircase. In the ancient Dutch tradition, is linked to the world, knowing only too well that beyond geometry there is only a shipwreck. And drawing a parallel between the two great seafaring nations I would like to quote the words of the great Portuguese poet: “Portugal is the country where the land ends and the sea begins.” And, in fact, do we not confound the buildings of Macao, Singapore, and northern Japan with those of these countries that are so thoroughly European and yet so exotic?

At the top of the stairs, among energetic young people and breathless senior citizens, we may admire the skilful display of the exhibits by the director. Far from being a celestial director, he is a true curator who is sensitive to the different emotional levels of light and beauty. Never in the history of architecture have larger works been seen which did not correspond to a sort of alliance between the patron and the artist, the bureaucrat and the engineer.

I will not carry on with the description, even if the basic tenet of Latin literature, as in the case of Virgil, was description rather than invention. But I cannot dwell upon the sorrows of Dido which have already been described to excess by the great Racine. Rather let us consider a number of the features which impress visitors, even the hasty ones, in the museum as a whole. Were you to ask the simplest person in Europe, there would only be one answer: the dome.

There are two main reasons for the magnificence of the dome: the first is its link with the architectural tradition of the classical world right up to the nineteenth-century Turinese architect Alessandro Antonelli; the second is that between river and sea it boldly signals the lie of the land in that country.

But now, just as if we were standing on the belvedere, we can view the museum as a whole, perhaps a lost whole that we only recognize thanks to those fragments of our lives which are also fragments of art and Europe of bygone days.

Aldo Rossi, July 1991

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment