Administrative building Shell

Shell House Berlin

No other modern metropolis is as closely associated with stone as Berlin. The austere façades in muted tones correspond to established notions of the appearance of German architecture. Nevertheless, the German capital offers a number of examples where stone is used in an unconventional and even dynamic manner.

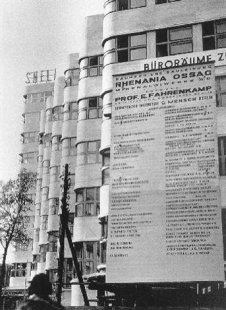

The administrative building for the Dutch oil company Shell is the first steel skeleton used for a high-rise in Berlin. It represents the most significant realization of an administrative building from the Weimar Republic period before stone was appropriated by national socialist propaganda, which sought to make it the material for government buildings for the next thousand years. The Shell-Haus is located in the Tiergarten district on the banks of the Landwehrkanal. The façade is clad in Roman travertine. The undulating southern side also rises in height from a five-story corner to a ten-story tower highlighting the main entrance. After World War II, it housed the city’s electric company Bewag. In the 1960s, the building was extended by Paul Baumgarten with a new wing clad in aluminum panels. That Shell-Haus continues to inspire today’s Berlin architects is evidenced by the quotes from the Sofitel hotel by Jan Kleihues, who, three-quarters of a century later, lent a similar dynamism to the solid stone façade, showing that stone cladding does not always have to adhere to strictly rationalist tectonics with sharply cut features.

The administrative building for the Dutch oil company Shell is the first steel skeleton used for a high-rise in Berlin. It represents the most significant realization of an administrative building from the Weimar Republic period before stone was appropriated by national socialist propaganda, which sought to make it the material for government buildings for the next thousand years. The Shell-Haus is located in the Tiergarten district on the banks of the Landwehrkanal. The façade is clad in Roman travertine. The undulating southern side also rises in height from a five-story corner to a ten-story tower highlighting the main entrance. After World War II, it housed the city’s electric company Bewag. In the 1960s, the building was extended by Paul Baumgarten with a new wing clad in aluminum panels. That Shell-Haus continues to inspire today’s Berlin architects is evidenced by the quotes from the Sofitel hotel by Jan Kleihues, who, three-quarters of a century later, lent a similar dynamism to the solid stone façade, showing that stone cladding does not always have to adhere to strictly rationalist tectonics with sharply cut features.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment