Museum of the Roman Theater of Cartagena

Museo del Teatro Romano de Cartagena

|

With this precedent, there could be no better project for the Madrid-based Moneo than the restoration of the ancient Roman theater in Cartagena, Spain, which also included the creation of an adjoining museum housed in two buildings and the design of a park to embrace the pieces of the architectural composition. Commissioned in 1999 and open to the public in 2008, this work allowed Moneo to bring together several of his fundamental concerns about architecture, building, and the city.

The abundance of ideas often imbued in a project by Moneo, which at times results in dense or disconcerting buildings, becomes increasingly successful the more complex the commission. In the case of the Cartagena project, his accomplishment is great because both intervention and invention were required—in the museum buildings, in the powerful Roman theater itself, and at various points throughout the city. Moneo’s architectural hand, in essence, has struck a balance between the singularity of each building in the complex and its relationship to the city—past and present.

Reconciliation between architecture and the city is an important idea evident in many projects throughout this prolific architect’s career. One early and clear example is Bankinter (1976), where he seamlessly inserted a rather large banking and office building behind a small, 19th-century palace on a main boulevard of Madrid. A more recent example of the need to achieve a careful balance between city and edifice can be seen in the extension to that city’s acclaimed Prado Museum [record, March 2008, page 118], where the pieces of a varied and delicate puzzle—a historic museum, a new underground addition to it, and a new building around a cloister—must fit together not only for function’s sake, but also to strengthen the city’s fabric.

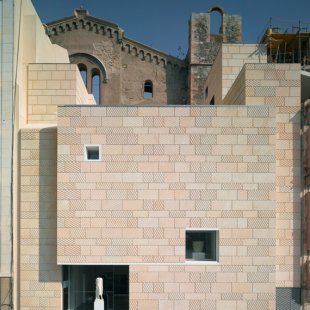

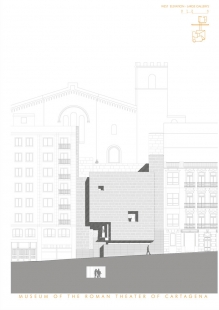

In Cartagena, Moneo seems to have been conscious of a city formed by memories, as well as a city shaped by the present. He opted to restore the 18th-century Riquelme Palace and allow it to form a dialogue with the town hall of Cartagena, a building begun in 1900. His new addition to it, which houses the first part of the Roman Theater Museum, while clearly modern in materials and form, is recessed to allow the palace a prominent place on the square. The museum’s exhibition galleries are located in a second building that respects the scale of the city, but its textured stone facade, punctuated by relatively few windows, is clearly a 21st-century building. The restoration of the Roman theater itself, the result of the difficult and delicate strategy of adding new to old, does not compromise the old—with additions that are capable of being reversed, if need be. Throughout, visitors can move easily and honestly between past and present.

This trajectory (or promenade) created by Moneo, extending from the city’s sea level to the higher ground of the museum culminating in the Roman theater, reflects the architect’s recurring position on the nature of a museum. Architecturally, his buildings and public spaces unfold as one walks through the city. Within the museum, the connection from one building to another via underground corridor reinforces the notion of journey and discovery—a device Moneo first used to connect buildings for his expansion of the Museum of Fine Arts Houston (2000). There, with an installation by James Turrell, he created a transitional preparatory space, making one’s arrival at the new galleries even more interesting and dramatic.

The progression in Cartagena from the lower-level exhibitions to the higher level and finally out to the theater is as much an architectural tour as it is a museum visit. Allowing its patrons to be conscious of space, as well as the texture and color of the building materials, is something that contributes to the memorable quality of a Moneo building. In the Mérida Museum of Roman Art, space and light are experienced in tandem with the art—fostering the architect’s idea of the museum as sacred space, whereby the building enhances the actual content of the museum. Likewise, in the Los Angeles Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels (2002), the required walk via an ambulatory that extends from the entrance to the back of the sanctuary is a clear expression of a journey where one becomes conscious of the magnitude of the building and the quality of light filtering through the alabaster from above. Yet again, Moneo’s interiors in Cartagena receive light from above and provide generous space for the contemplation of the works of art, reflecting a clear understanding and appreciation of the objects. It should be remembered that Moneo’s concepts of promenade and museums embody an element of freedom that allows the public to choose a path and to vary it spontaneously, a welcome attitude of respect toward the museum visitor.

Martha Thorne has been executive director of the Pritzker Architecture Prize since 2005.

0 comments

add comment